Covid: What might a third wave look like?

- Published

- comments

Lockdown is, step-by-step, beginning to ease across the UK. Next week, the stay-at-home order will be lifted in England and people can start mixing in small groups outdoors.

But with infection rates rising in Europe, the British public is also being warned of the risk of a third wave.

The prime minister himself says it is only a matter of time before the wave from Europe washes up on our shores. But with more than half of adults vaccinated, what would that look like?

The threat is already on these shores

While the outbreaks in Europe have been portrayed as the threat, we should not forget the virus is still lurking here. Infection rates have dropped dramatically since the turn of the year - there has been a 12-fold fall in daily cases being reported.

But that still leaves more than enough infection circulating that could easily take off. The Office for National Statistics estimates that, along with asymptomatic cases, there could be more than 100,000 infectious people out there.

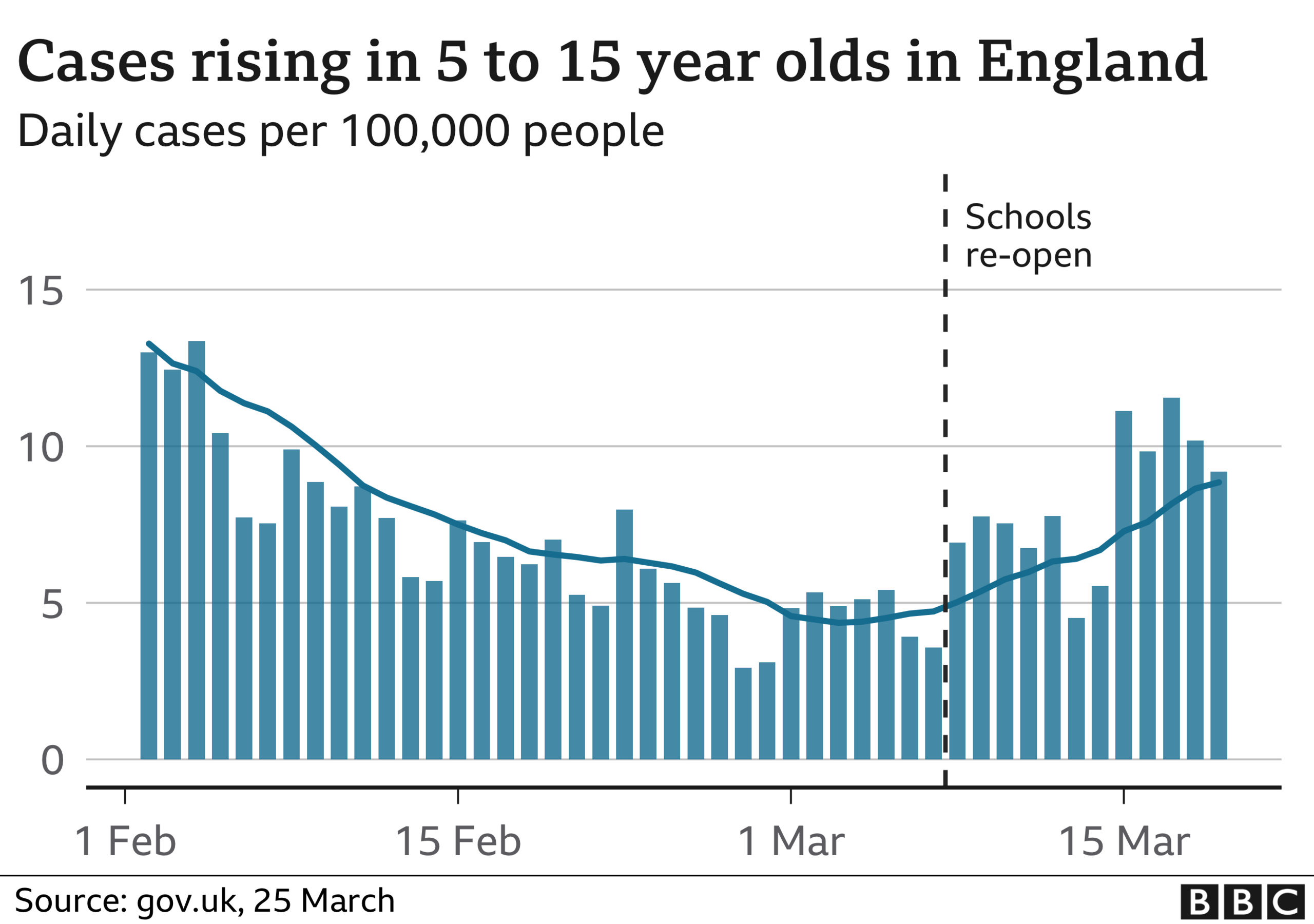

Already there are signs of a slight increase in cases among children following the return to schools in England.

Prof Christina Pagel, from University College London, says some of the increase is undoubtedly because of more testing - secondary school pupils have been offered regular on-the-spot rapid tests since their return to school to pick up asymptomatic cases.

But that, she says, cannot account for it all. She is concerned this is the start of an upward trend, pointing out that many parents will not have had their first dose yet - rollout has been limited to the over-50s and younger adults with health conditions. The break for Easter will help slow the spread but that will only be temporary, she fears.

Why care is needed even with vaccine rollout

But if cases continue to rise, does this matter? After all, 99% of Covid deaths have been in the groups now vaccinated.

The link between infections and serious illness or death has been "severely weakened", says diseases expert Prof Mark Woolhouse, of Edinburgh University.

But if infection levels rise high enough the virus "will find those" who are unvaccinated and those for whom the vaccine hasn't worked, he says.

While the vaccines are good - they significantly reduce the risk of falling ill and for those who do develop symptoms there is a strong likelihood it will be a fairly mild cough, fever or short period of breathlessness - they are not 100% perfect.

So Prof Woolhouse warns there could still be significant numbers of deaths, even if the threat to the NHS is much reduced.

What nobody can be sure of is just how quickly and by how much infection levels could rise in the coming months.

The natural R rate - how many people the average person who is infected passes the virus on to - was between three and four for this coronavirus, but with the new more contagious variant dominant, it could now be around five, some believe.

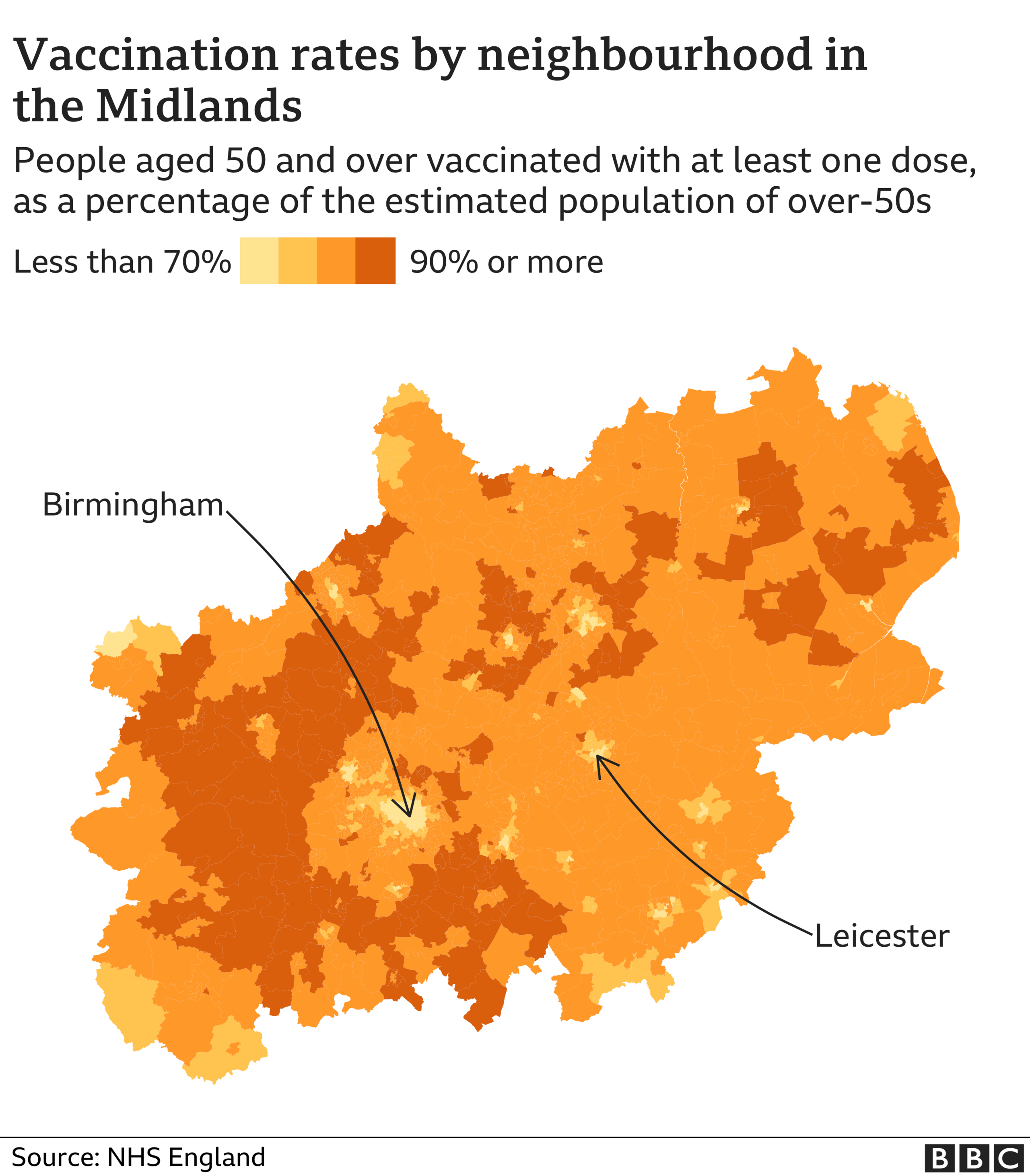

Dr Duncan Robertson, a disease modeller at Loughborough University, believes we are in "essentially a new epidemic". "This is the first time we are lifting restrictions with the new variant - it could take off and those areas with the lowest vaccination rates will be vulnerable."

Factors that will determine third wave

There are a number of issues that will be crucial in determining exactly what happens from here.

As well as protecting those vaccinated, the vaccine programme will also help slow transmission. Early evidence suggests the AstraZeneca jab could stop two-thirds of people who are vaccinated from passing it on.

On top of that those who have already been infected - estimated to be about a quarter of the population - will have some immunity.

Secondly, seasonality could help. Respiratory viruses tend to thrive in the winter, but are less likely to spread in the spring and summer.

Because this is a new virus, it could take some time to settle into a seasonal pattern, but certainly the changing seasons are likely to have some impact.

UK chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty says it is possible a significant rise may not actually come until the winter, giving more time for the vaccination programme to rollout.

Speaking this week, he said the UK should be confident the "path from here does look better", but we should still expect "bumps and twists" along the way.

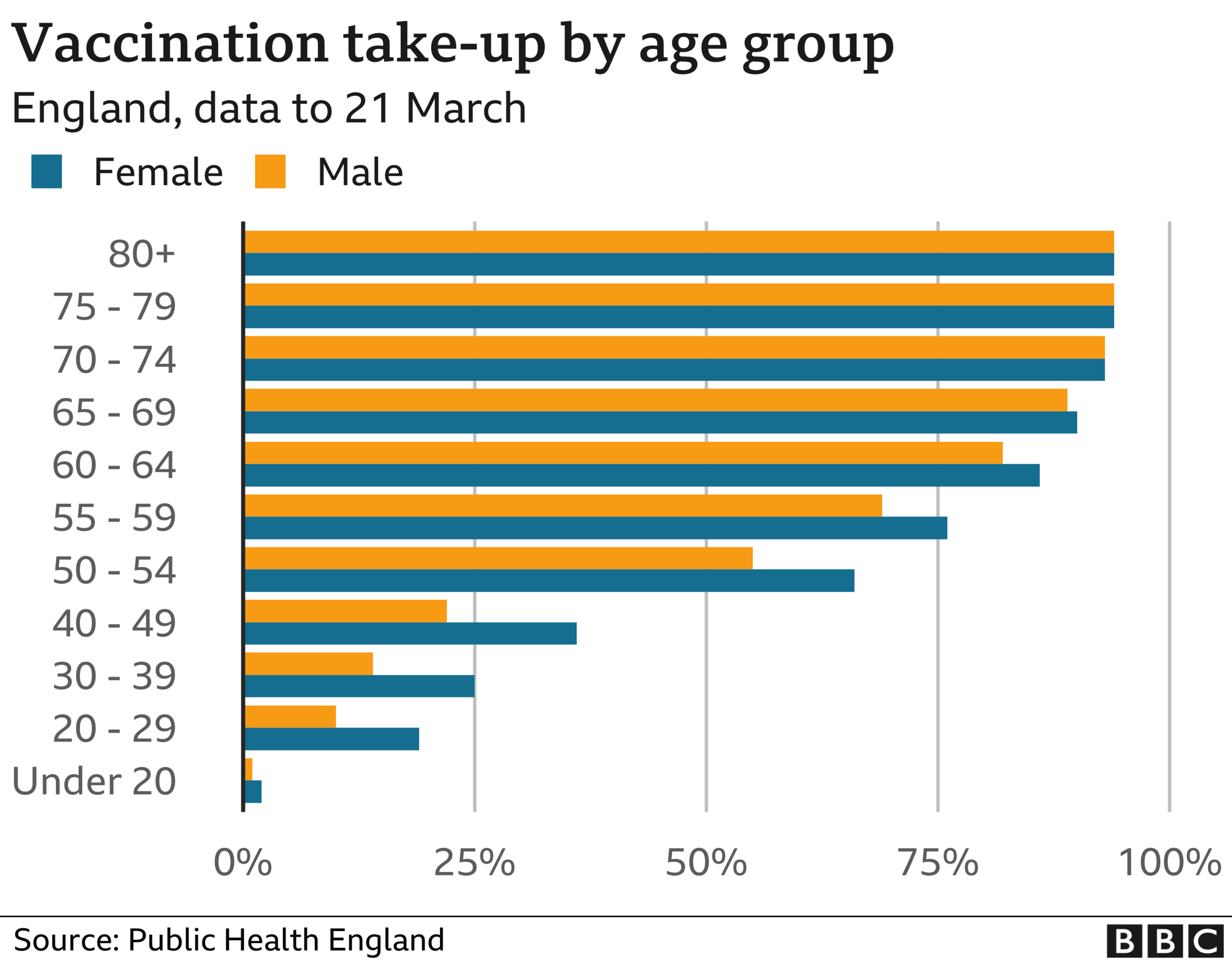

The most immediate problem, he said, was likely to be local outbreaks - and variation in uptake between different areas leaves some places particularly vulnerable.

Meanwhile, in the longer term, variants that can spread more easily because they can evade some of the immune response could come into play, Prof Whitty said.

The next unknown is the behaviour of the public. By far the biggest risk factor for spreading the virus is mixing indoors in homes, says Prof Woolhouse. "We know most outdoor activities are very safe, we know there has never been a surge in cases following school opening and the risks in retail and hospitality can be mitigated.

"But we cannot police what happens in people's homes - that is the perfect environment for the virus to spread."

How bad could it be?

The "gut reaction" of most people will be to think everything will be fine, says Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, a Cambridge University expert in understanding risk, and that we can "start enjoying ourselves again".

But we should not "trust our intuition on this", he says. That means taking each step very cautiously.

"The government is determined to not take steps back so that could mean taking longer to take steps forward."

The aim, of course, is to balance the need to open society while trying to control the virus. While some people have called for a "Zero Covid" approach, the government and its advisers are clear this cannot be achieved given the nature of the virus, which can spread without people being aware they are infected.

This week, chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance said there was basically "zero chance" of zero Covid.

So how bad will the third wave get? Modelling done for the government has suggested as many as 30,000 people could die by the summer of 2022, external, even with a gradual reopening and good vaccine rollout.

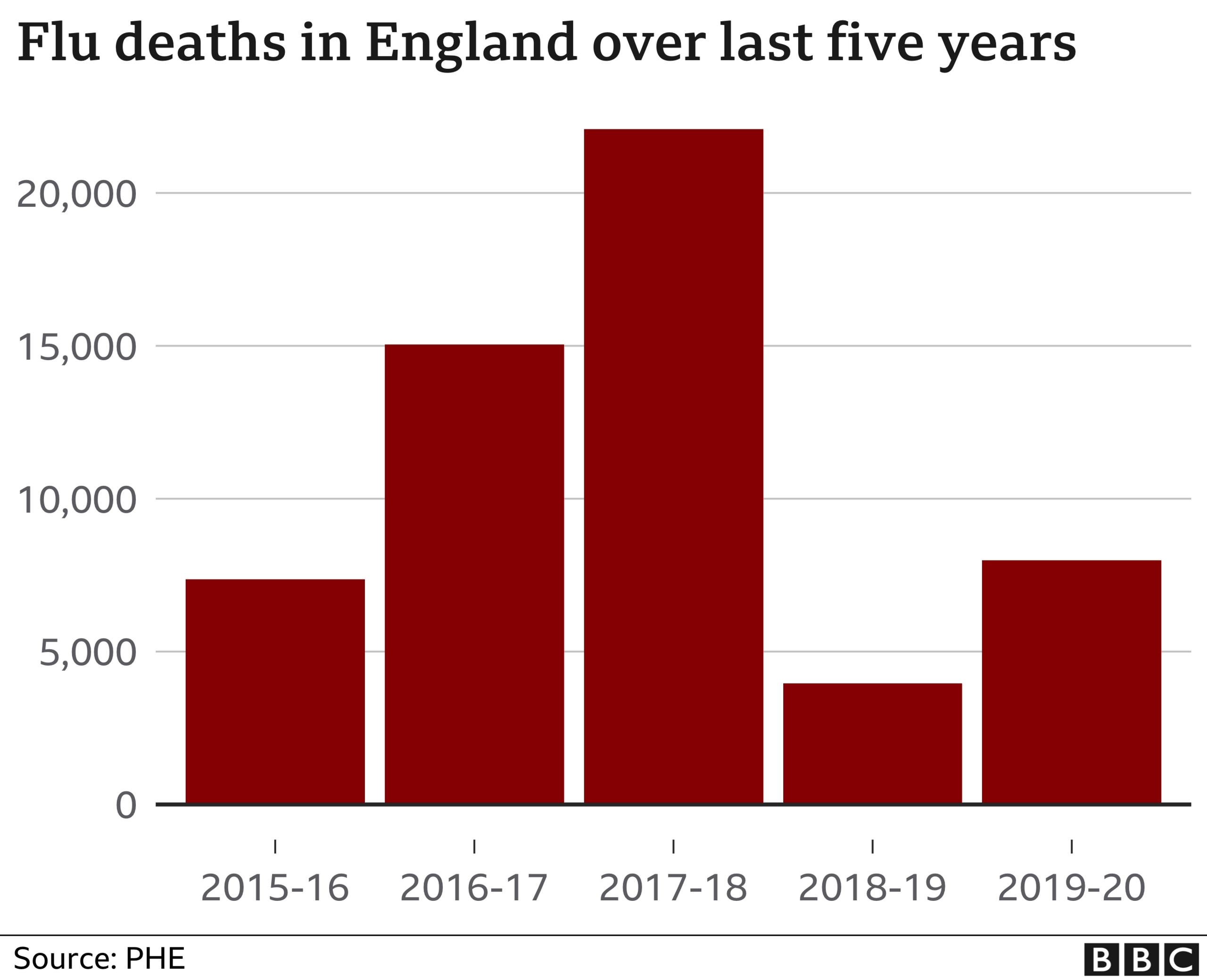

That is four times fewer than the number of deaths we have seen over the past year. And while it sounds high, it is worth noting that in a bad winter, 25,000 people can die from flu. But the toll could be much much higher - more than double that - if things do not go as well as assumed, the modelling suggested.

There are, of course, as always caveats around these models. But they should act as a warning - while the UK may be in a strong position, nothing should be taken for granted with this virus.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

LOCKDOWN RULES: What are they and when will they end?

OXFORD JAB: What is the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine?

VACCINE: When will I get the jab?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020