Gene therapy: 'Now I can see my own face again'

- Published

"Last year, for a lot of people was a dark and miserable year, but for me it was probably easily the best year of my life."

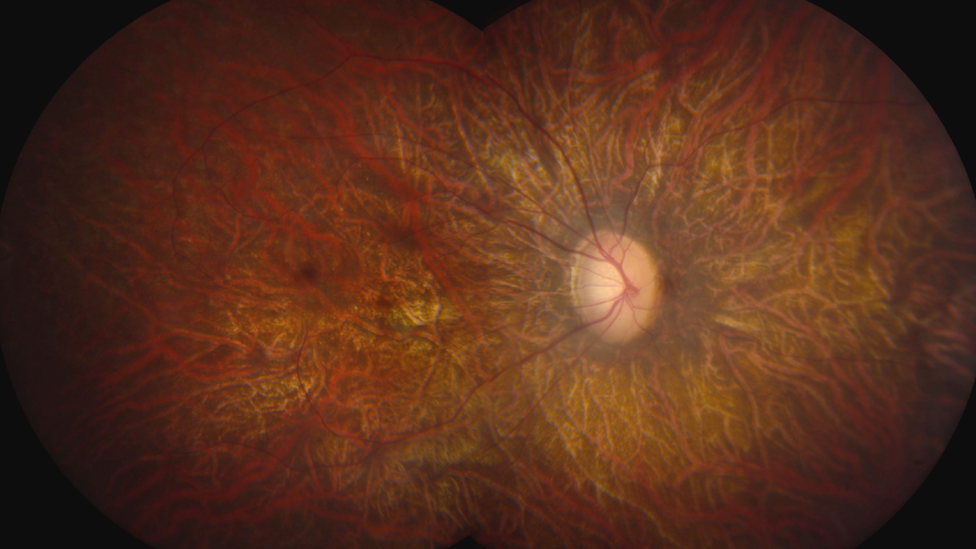

Jake Ternent has been gradually losing his central vision since birth, because of a rare inherited genetic eye condition.

And, despite the pandemic, 2020 was a landmark year for the 24-year-old, from County Durham, who became the first person in the UK to receive a revolutionary new gene therapy on the NHS.

"It was science fiction, about a year-and a half ago, to think that my eyesight could improve at all," Jake told the BBC.

His condition - leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) - is caused by having two faulty copies of a gene called RPE65, which is essential for maintaining healthy photoreceptor cells in the retina.

In 2019 the NHS agreed to fund the treatment, Luxturna, the first in a new generation of gene therapies for conditions causing blindness. It costs about £600,000 per patient to treat both eyes, though the NHS has agreed a confidential discount with the makers Novartis.

About 100 people in the UK are likely to be eligible for the gene therapy, which is being carried out at four hospitals in England.

Jake underwent the procedure, which is intended to halt further sight loss, at London's Moorfields Eye Hospital in January last year.

Jake says that not only has it stabilised the sight in his right eye, it also appears to have reversed some of the decline in vision he has experienced in recent years.

"Just being able to see facial features on my own face is something that I haven't been able to do for years," he explains.

Jake's mum Dianne says he has become more independent since the procedure

Jake recently had the gene therapy on his left eye, and will need to wait a couple of months to see if this further improves his vision.

A passionate football fan, he can now follow matches on television, and make out the ball as it is passed from player to player.

He says: "It is something quite small for a regular-sighted person but, if you can't see who's got the ball, it takes you out of the game."

Jake's mum Dianne says she has seen him become more independent since the procedure.

"He feels he has the confidence to do a little bit more now, whereas he just wouldn't attempt many things before the operations."

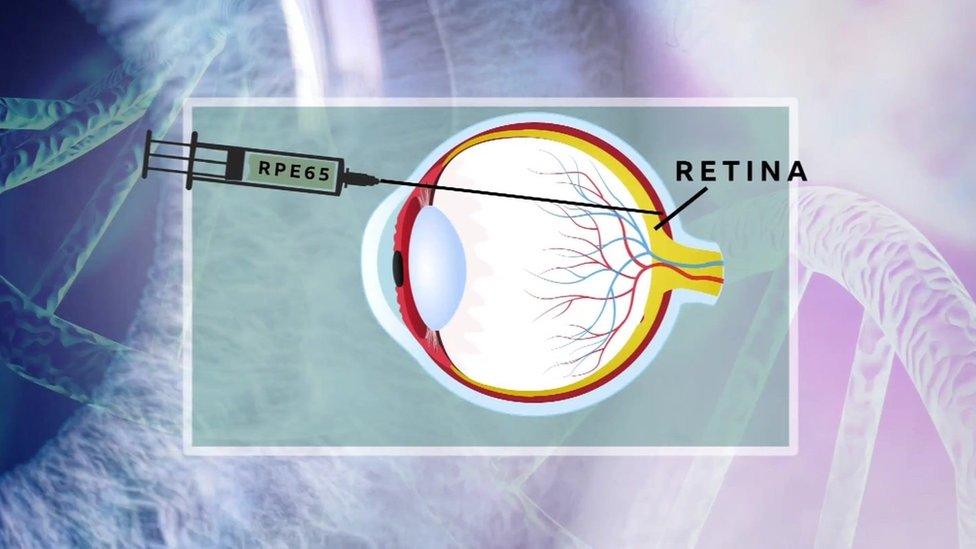

The treatment involves injecting copies of a faulty gene into the back of the eye

How the therapy works

The injection delivers working copies of a faulty gene, RPE65, into the retina at the back of the eye.

The DNA is encased in a harmless virus which breaks into the retinal cells.

Once inside the nucleus, the replacement gene kick-starts production of the RPE65 protein essential for healthy vision.

'Making a real difference'

Prof James Bainbridge, Jake's surgeon at Moorfields, says the results from the first patients are encouraging.

"It's fantastic to see these people reporting improvements even weeks after the surgery. It is making a real difference to their lives, and the hope is that these benefits will last for many years or even their lifetime."

And he says it offers potential for other conditions.

"Until quite recently we've had very little to offer people with inherited blindness, but this is really transformational. It provides an opportunity to provide hope for people not only with this specific condition, but people with other similar disorders, that they can protect their sight in the long term.

"If the treatment can arrest the decline, that's profound."

Matthew Wood, 48, has the same retinal condition and has also been slowly losing his sight since childhood. He lost his central vision around 10 years ago, and says it's had a severe impact on his daily life.

"Through all the years that I was growing up I was told there was no treatment and no hope to impact the cause of the disease," he said.

Matthew's wife doesn't have to help him with everyday things as much since his therapy

Since receiving the gene therapy last year at Oxford Eye Hospital he has noticed some subtle, but welcome, changes in his vision.

"I think there is an improvement. Today, coming into this park, I noticed that there are railings above the entrance to the gate. I've been here many times but never been able to see them before."

His wife Yvonne has also noticed she doesn't have to help Matthew as much.

"He doesn't have to ask me to help with every little thing any more, such as the setting on the washing machine or coffee maker; everyday things that people take for granted, Matthew can now do himself."

His second gene therapy procedure is due to take place in May, and Matthew hopes it will prevent any further loss of sight.

"If it puts off another decline, that's going to be amazing."

In all, about a dozen people in the UK have received the gene therapy - including several children, who stand to benefit most, as they can be treated before permanent damage is done.

Robert Henderson, a child sight specialist at Great Ormond Street Hospital, said: "My hope is that if we can diagnose and treat these children at a really young age, we will have a far greater chance of giving them near normal vision."

Related topics

- Published4 May 2015

- Published8 February 2012