Covid: Why has the Delta variant spread so quickly in UK?

- Published

The Delta variant of the virus causing Covid-19 has caused infections to spike in the UK once more, preventing the planned relaxation of lockdown in England. But is it really faring worse than other countries?

Where is the Delta variant?

Labs around the world that analyse the virus's genetic material have been sharing their findings to a global database. When you look at this, the UK looks like it has more cases of the Delta variant than most of the rest of the world.

A total of 75,953 cases, external of Delta were sequenced in the UK up to 16 June, up from 42,323 the previous week.

By the week beginning 14 June, 2,853 Delta cases had been identified in the US, 747 in Germany, 277 in Spain and 97 in Denmark, according to a global monitoring website, external.

But this is not a definitive record of how many cases there are - it's a record of how many are spotted, and the UK has a very good system for spotting variants.

So it's likely these figures disguise a much greater incidence of the variant in some countries that carry out less sequencing - genetic analysis - of the virus.

For example, there were 875 Delta cases identified in India in the week beginning 3 May, when the virus was raging, and just 142 in the past four weeks. That's despite the country recording between half a million and two million new cases a week since the start of May, with Delta believed to be the dominant variant.

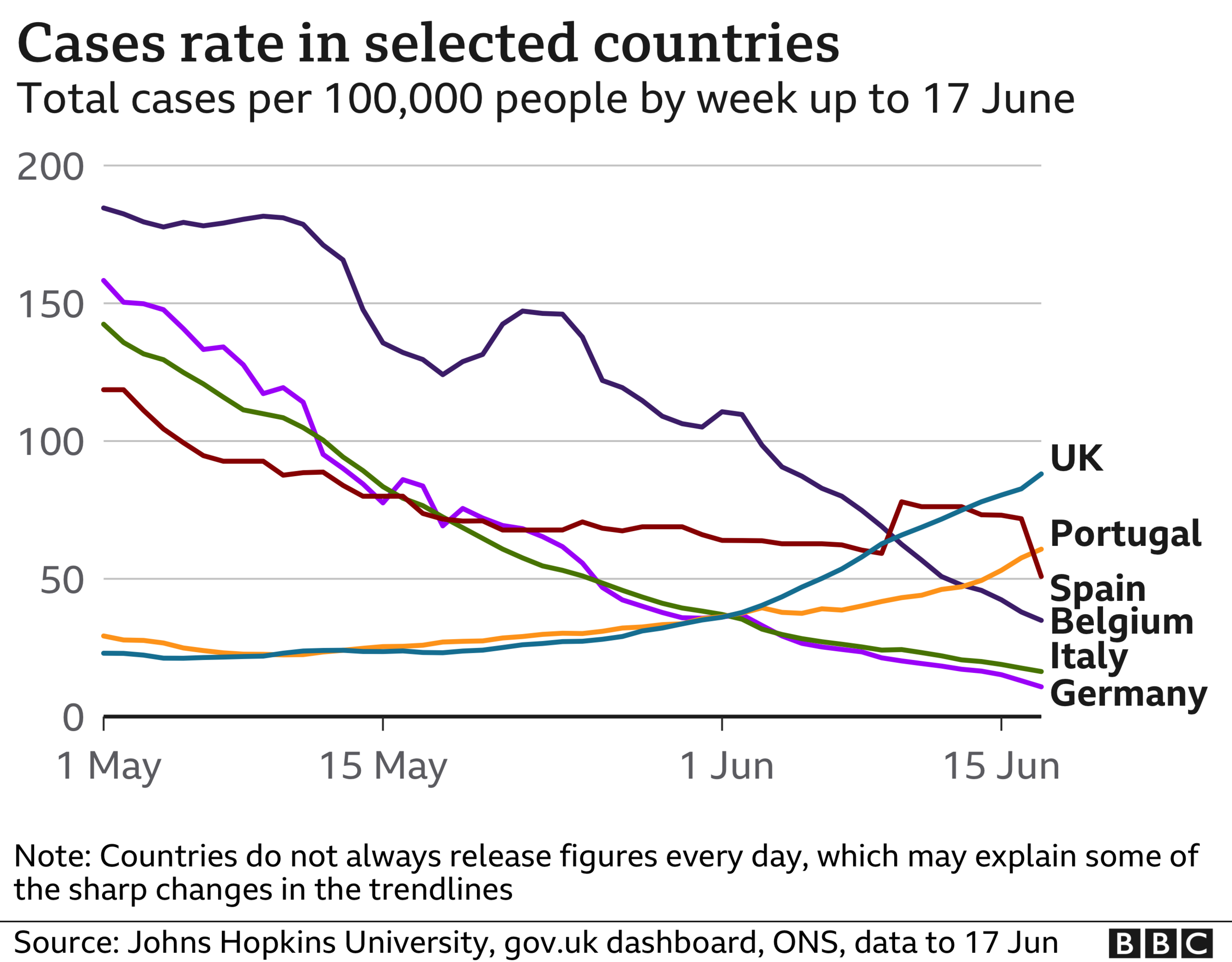

This doesn't mean there isn't a problem in the UK though - cases have generally been falling across mainland Europe. And some countries that do a lot of sequencing, such as Denmark, have not seen the Delta variant take off.

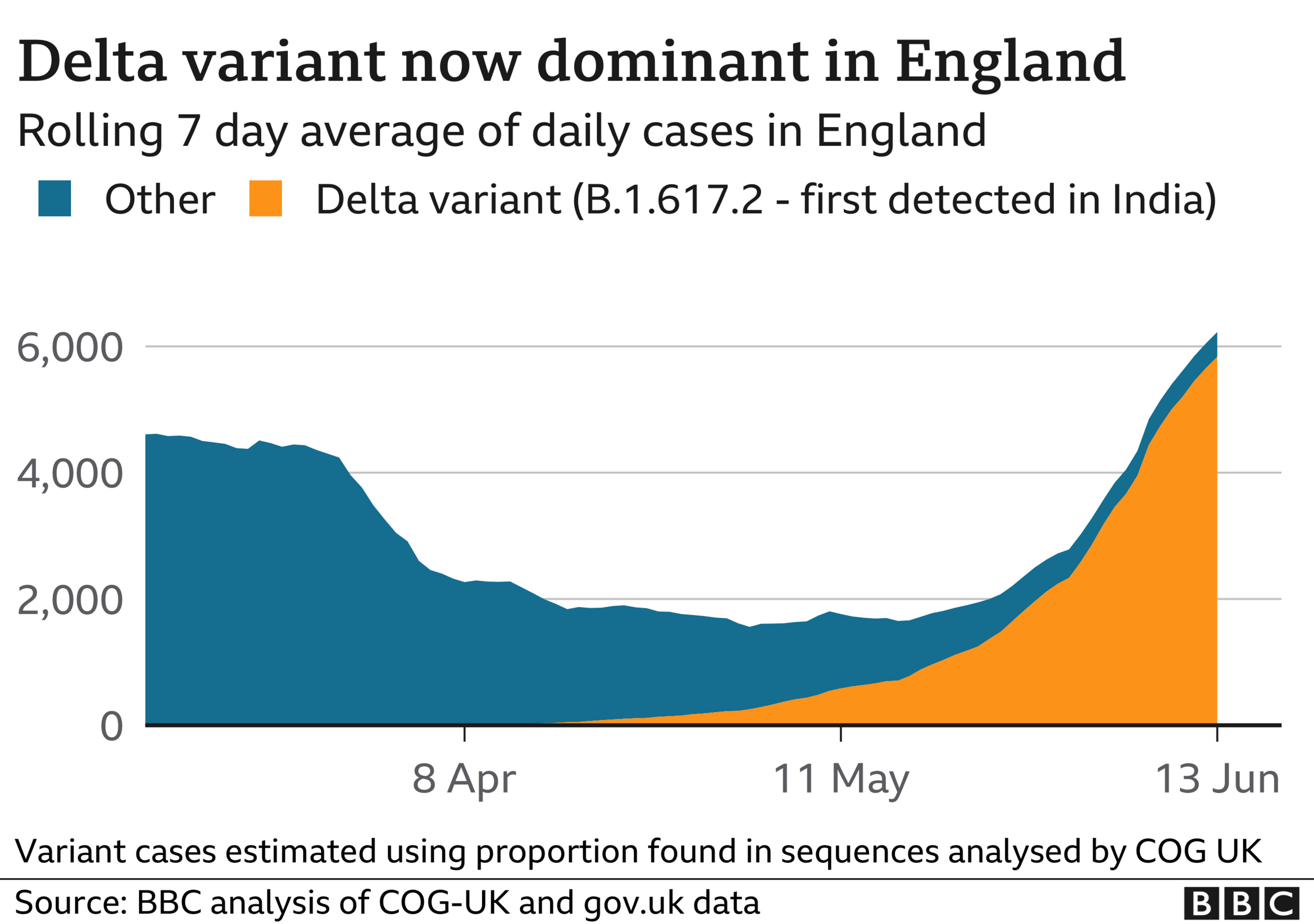

In England, 38,000 cases of the Delta variant were recorded in the past 28 days.

The Scottish government says the variant is responsible for "the overwhelming majority", external of new cases.

Northern Ireland's government has warned that it's likely to become the dominant strain and the Welsh government says the Delta variant is driving a rise in infection, with the country at the start of a third wave of coronavirus.

Why is it so bad in the UK compared with other countries?

Experts believe a major factor is the number of cases that were introduced into the UK in a short space of time, because of the volume of travel.

Public Health England figures show the variant was introduced at least 500 times by travellers.

Dr Jeffrey Barrett, from the Sanger Institute, which analyses the genetic material from Covid-test swabs to work out which mutations they contain, said he believed the true number was likely to be more than 1,000.

This is important because of the irregular way the virus spreads. We talk about the R number meaning that, with no distancing or infection control measures in place, one person might infect three others on average.

But in reality, it's not the case that every single person infects three others. Instead, one person might infect 30 others while another person infects no-one at all - whether because of differences in their biology, behaviour or living conditions.

There's an element of chance - if five people arrive in the UK carrying the variant, you could get lucky and none of them would pass it on. If 500 come in, it's just more likely at least one will pass on their infection, or even be a super-spreader.

So the difference between five and 500 travellers entering with the Delta variant won't be exactly 100 times the infections - it could be the difference between the variant fizzling out altogether and it taking off.

On top of this, the Delta variant entered the UK at a time when restrictions were being relaxed and in cold weather. The cold snap would have seen more people indoors and thus spreading infection, but also the virus surviving longer outdoors.

Will other countries follow?

Experts believe some countries may already be heading the same way as the UK - but that they have genetic sequencing programmes which analyse fewer swabs, more slowly, meaning we can't see it in the data yet.

And in some countries like the US, the variant appears to have been introduced slightly later - so it could begin to rise in the coming weeks.

Dr Muge Cevik, an infectious disease specialist at the University of St Andrews, said that, in time, we may see a similar trajectory in other countries, adding such a prospect was "much more worrying in countries with low vaccination rates".

It is quite likely to become the dominant variant in other countries, and possibly worldwide, she said.

The variant is considerably more transmissible and we know - including from the example of the Alpha variant first identified in Kent - that the virus eventually finds a way to spread.

Could it have been prevented?

According to the Civil Aviation Authority, 42,406 people travelled in both directions between India and the UK in April.

Less travel would have meant fewer opportunities for the variant to enter.

In January, Sage, the government's scientific body, had warned, external that: "No intervention, other than a complete, pre-emptive closure of borders, or the mandatory quarantine of all visitors upon arrival in designated facilities, irrespective of testing history, can get close to fully prevent the importation of cases or new variants."

The government placed India on the red list - meaning people returning would face mandatory hotel quarantine - on 23 April.

This was after the World Health Organization had classified Delta as a "variant of interest" and after it was known to be in the UK, but before it had been designated as a "variant of concern" by the UK health authorities.

And while it was not immediately clear which of several variants was causing problems in India, it was becoming increasingly clear the country was experiencing a devastating toll from the virus.

But Dr Cevik said "eventually it was always going to take off" in the UK, though measures could have delayed importation.

She pointed out even Australia, which has among the strictest border controls in the world, has already had Delta outbreaks, though they've been relatively small.

And, she added, the threat of "red-listing" countries may well incentivise them to stop testing and sequencing.

"We won't be able to completely stop variants coming," she said, and the best solution was to vaccinate as many people in the world as possible.