Ivermectin: How false science created a Covid 'miracle' drug

- Published

Ivermectin has been called a Covid "miracle" drug, championed by vaccine opponents, and recommended by health authorities in some countries. But the BBC can reveal there are serious errors in a number of key studies that the drug's promoters rely on.

For some years ivermectin has been a vital anti-parasitic medicine used to treat humans and animals.

But during the pandemic there has been a clamour from some proponents for using the drug for something else - to fight Covid and prevent deaths.

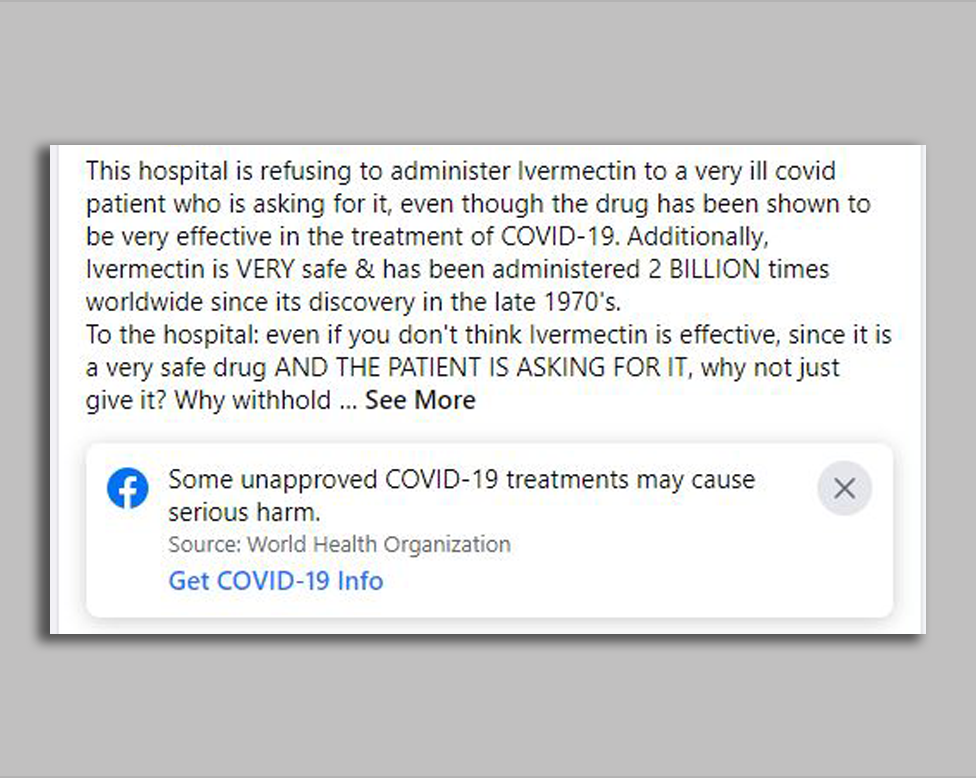

The health authorities in the US, UK and EU have found there is insufficient evidence for using the drug against Covid, but thousands of supporters, many of them anti-vaccine activists, have continued to vigorously campaign for its use.

Ivermectin was approved for Covid treatment in Peru in May 2020

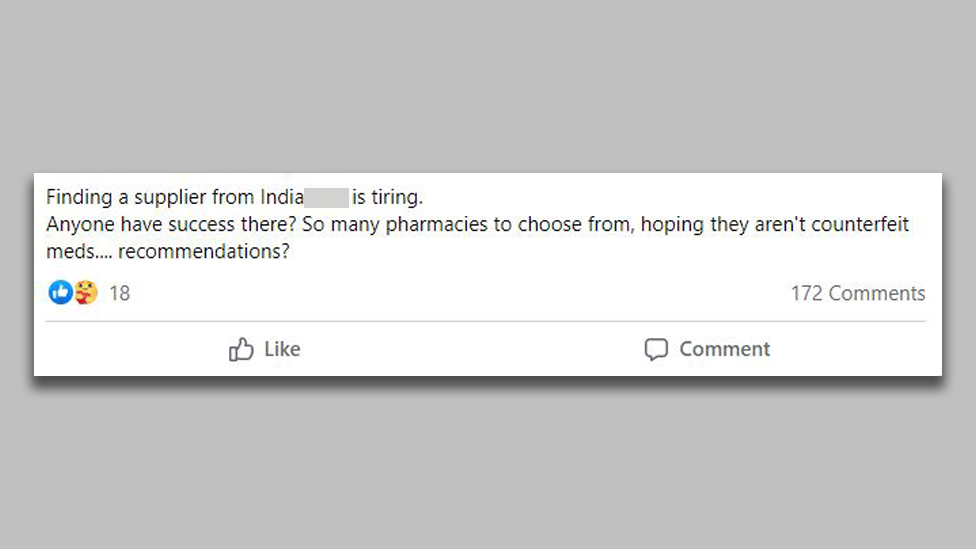

Members of social media groups swap tips on getting hold of the drug, even advocating the versions used for animals.

The hype around ivermectin - based on the strength of belief in the research - has driven large numbers of people around the world to use it.

Campaigners for the drug point to a number of scientific studies and often claim this evidence is being ignored or covered up. But a review by a group of independent scientists has cast serious doubt on that body of research.

The BBC can reveal that more than a third of 26 major trials of the drug for use on Covid have serious errors or signs of potential fraud. None of the rest show convincing evidence of ivermectin's effectiveness.

Dr Kyle Sheldrick, one of the group investigating the studies, said they had not found "a single clinical trial" claiming to show that ivermectin prevented Covid deaths that did not contain "either obvious signs of fabrication or errors so critical they invalidate the study".

Major problems included:

The same patient data being used multiple times for supposedly different people

Evidence that selection of patients for test groups was not random

Numbers unlikely to occur naturally

Percentages calculated incorrectly

Local health bodies unaware of the studies

The scientists in the group - Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, Dr James Heathers, Dr Nick Brown and Dr Sheldrick - each have a track record of exposing dodgy science. They've been working together remotely on an informal and voluntary basis during the pandemic.

They formed a group looking deeper into ivermectin studies after biomedical student Jack Lawrence spotted problems with an influential study from Egypt. Among other issues, it contained patients who turned out to have died before the trial started. It has now been retracted by the journal that published it.

The group of independent scientists examined virtually every randomised controlled trial (RCT) on ivermectin and Covid - in theory the highest quality evidence - including all the key studies regularly cited by the drug's promoters.

RCTs involve people being randomly chosen to receive either the drug which is being tested or a placebo - a dummy drug with no active properties.

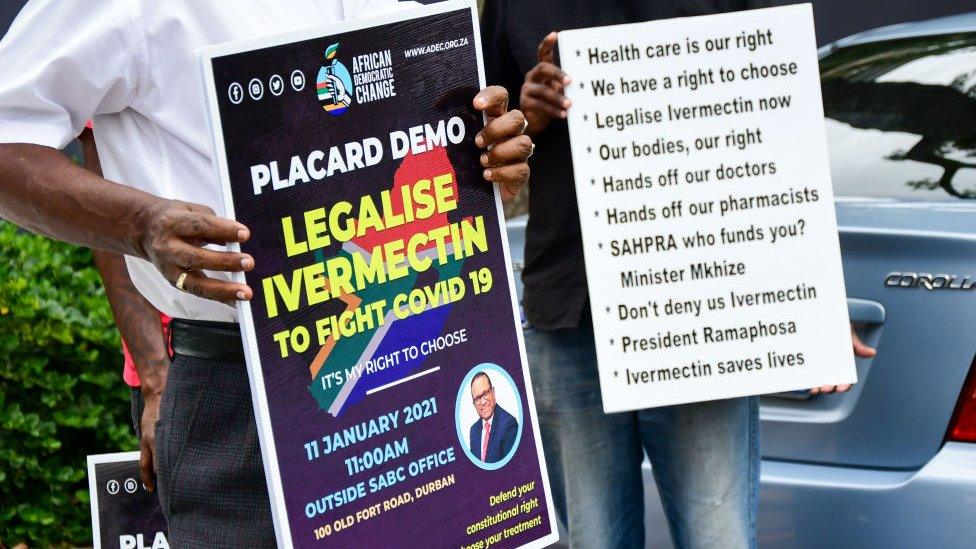

Some South Africans took to the streets to demand that the authorities allow ivermectin to be used

The team also looked at six particularly influential observational trials. This type of trial looks at what happens to people who are taking the drug anyway, so can be biased by the types of people who choose to take the treatment.

Out of a total of 26 studies examined, there was evidence in five that the data may have been faked - for example they contained virtually impossible numbers or rows of identical patients copied and pasted.

In a further five there were major red flags - for example, numbers didn't add up, percentages were calculated incorrectly or local health bodies weren't aware they had taken place.

On top of these flawed trials, there were 14 authors of studies who failed to send data back. The independent scientists have flagged this as a possible indicator of fraud.

The sample of research papers examined by the independent group also contains some high-quality studies from around the world. But the major problems were all in the studies making big claims for ivermectin - in fact, the bigger the claim in terms of lives saved or infections prevented, the greater the concerns suggesting it might be faked or invalid, the researchers discovered.

While it's extremely difficult to rule out human error in these trials, Dr Sheldrick, a medical doctor and researcher at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, believes it is highly likely at least some of them may have been knowingly manipulated.

A recent study in Lebanon was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly - suggesting many of the trial's apparent patients didn't really exist.

The study's authors told the BBC that the "original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file" and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

Another study from Iran seemed to show that ivermectin prevented people dying from Covid.

But the scientists who investigated it found issues. The records of how much iron was in patients' blood contained numbers in a sequence that was unlikely to come up naturally.

And the patients given the placebo turned out to have had much lower levels of oxygen in their blood before the trial started than those given ivermectin. So they were already sicker and statistically more likely to die.

But this pattern was repeated across a wide range of different measurements. The people with "bad" measurements ended up in the placebo group, the ones with "good" measurements in the ivermectin group.

The likelihood of this happening randomly across all these different measurements was vanishingly small, Dr Sheldrick said.

Dr Morteza Niaee, who led the Iran study, defended the results and the methodology and disagreed with problems pointed out to him, adding that it was "very normal to see such randomisation" when lots of different factors were considered and not all of them had any bearing on participants' Covid risk.

But the Lebanon and Iran trials were excluded from a paper for Cochrane - the international experts in reviewing scientific evidence - because they were "such poorly reported studies". The review concluded there was no evidence of benefit for ivermectin when it comes to Covid.

The largest and highest quality ivermectin study published so far is the Together trial at the McMaster University in Canada. It found no benefit for the drug when it comes to Covid.

Ivermectin is generally considered a safe drug, though there have been some reports of side effects.

Calls over suspected ivermectin poisonings in the US, external have increased a lot but from a very small base (435 to 1,143 this year) and most of these cases were not serious. Patients have had vomiting, diarrhoea, hallucinations, confusion, drowsiness and tremors.

But indirect harm can come from giving people a false sense of security, especially if they choose ivermectin instead of seeking hospital treatment for Covid, or getting vaccinated in the first place.

Dr Patricia Garcia, a public health expert in Peru, said at one stage she estimated that 14 out of every 15 patients she saw in hospital had been taking ivermectin and by the time they came in they were "really, really sick".

Large pro-ivermectin Facebook groups have turned into forums for people to find advice on where to buy it, including preparations meant for animals.

Some groups regularly contain posts about conspiracy theories of ivermectin cover-ups, as well as pushing anti-vaccine sentiment or encouraging patients to leave hospital if they aren't getting the drug.

The groups often provide a gateway to more fringe communities on the encrypted app Telegram.

These channels have co-ordinated harassment of doctors who fail to prescribe ivermectin and abuse has been aimed at scientists. Dr Andrew Hill, from the University of Liverpool, wrote an influential positive review of ivermectin, originally saying the world should "get prepared, get supplies, get ready to approve [the drug]".

Now he says the studies don't stand up to scrutiny - but after he changed his view, based on new evidence emerging, he received vicious abuse.

A small number of qualified doctors have had an exaggerated influence on the ivermectin debate. Noted proponent Dr Pierre Kory's views have not changed despite the major questions over the trials. He criticised "superficial interpretations of emerging trials data".

Dr Tess Lawrie - a medical doctor who specialises in pregnancy and childbirth - founded the British Ivermectin Recommendation Development (Bird) Group.

She has called for a pause to the Covid-19 vaccination programme and has made unsubstantiated claims implying the Covid vaccine had led to a large number of deaths based on a common misreading of safety data.

When asked during an online panel what evidence might persuade her ivermectin didn't work she replied: "Ivermectin works. There's nothing that will persuade me." She told the BBC: "The only issues with the evidence base are the relentless efforts to undermine it."

Around the world it was originally not opposition to vaccines but a lack of them that led people to ivermectin.

The drug has at various points been approved, recommended or prescribed for Covid in India, South Africa, Peru and much of the rest of Latin America, as well as in Slovakia.

Health authorities in Peru and India have stopped recommending ivermectin in treatment guidelines.

In February, Merck - one of the companies that makes the drug - said there was "no scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against Covid-19".

In South Africa, the drug has become a battleground - doctors point out the lack of evidence but many patients desperately want access as the vaccine rollout has been patchy and problematic. One GP in the country described a relative, a registered nurse, who didn't book a coronavirus vaccine she was eligible for and then caught the virus.

"When she started getting worse, instead of getting proper assessment and treatment, she treated herself with ivermectin," she said.

"Instead of consulting a doctor, she continued with the ivermectin and got home oxygen. By the time I heard how low her oxygen saturation levels were (66%), I begged her daughter to take her to casualty.

"At first they were reluctant, but I convinced them to go. She passed away a few hours later."

Additional reporting by Shruti Menon