Covid: Shaken to the core, can the NHS cope this winter?

- Published

- comments

Heart attack and stroke victims are waiting twice as long in A&E, according to one expert

With autumn arriving, the NHS is bracing itself for a tough few months.

Covid, plus the return of normal winter illnesses and a growing backlog, could stretch the NHS to its limit.

How well equipped is the NHS for what is coming?

How busy are hospitals?

Hospitals have had to make drastic changes to the way they run since the start of the pandemic.

Extra infection control measures have been introduced and the need for social distancing has squeezed space at hospitals.

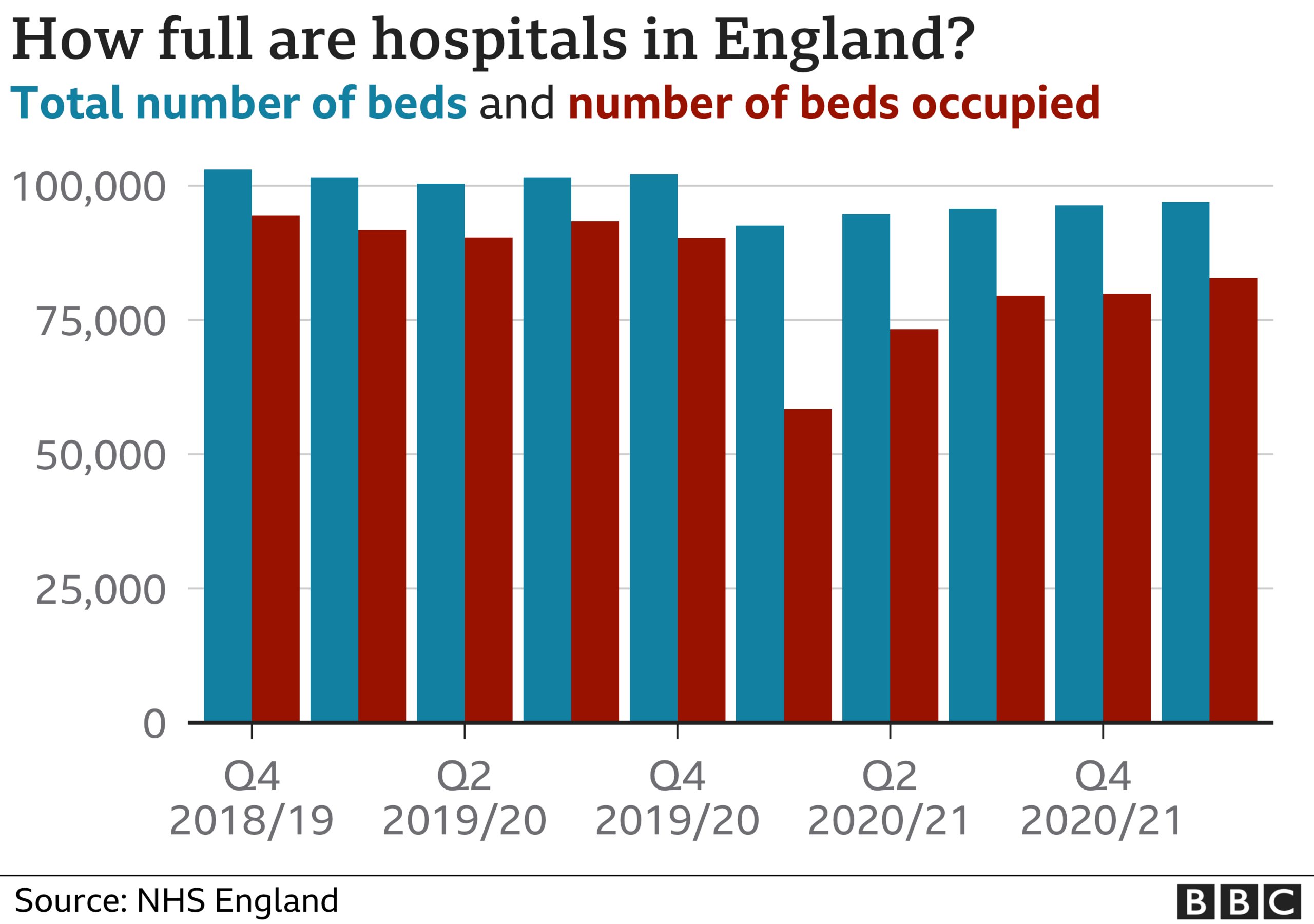

Some services have had to be moved off-site and the total number of beds has had to be cut by close to 10% across the UK. In England this led to a drop from just over 100,000 beds to just over 90,000.

Early in the pandemic lots of other care was stopped - mainly non-emergency treatments, such as hip and knee replacements.

This meant there were actually plenty of beds available in spring 2020 - as you can see from the red bars above.

But since then the NHS has tried to combine treating Covid patients with maximising the amount of other care being provided.

It means hospitals are pretty much full - around 85% of beds are occupied in the most recent period, which is the recommended maximum to maintain safe care.

Some wriggle room is needed to cope with surges in demand and to ensure beds can be cleaned between patients.

How many are Covid patients?

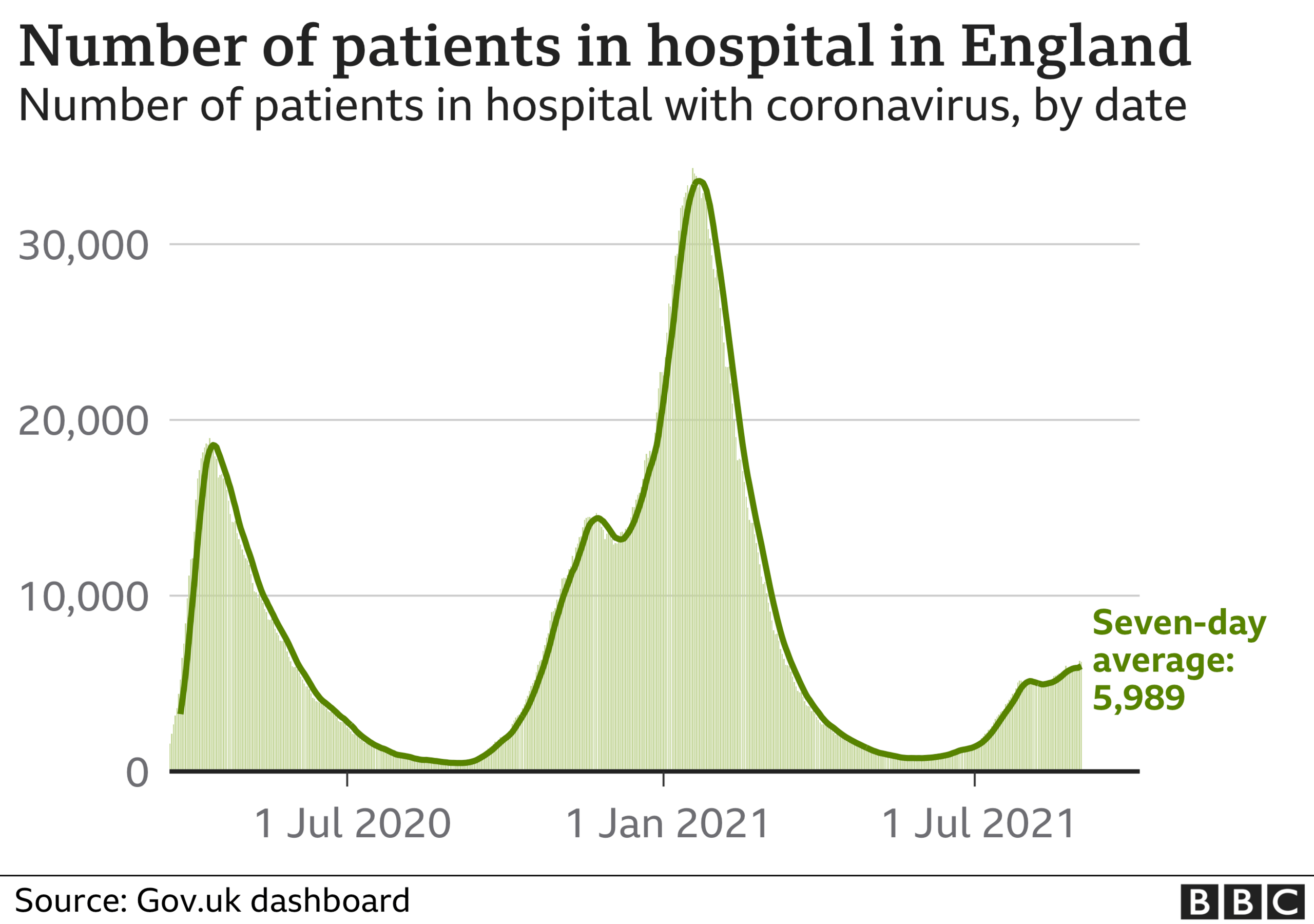

In the winter more than 40% of beds were occupied by Covid patients, placing a huge toll on the health service.

That is now down to under 7%.

These figures relate to England, but the picture is similar in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

That may not seem a lot, but for a health service that has always been run close to the bone, it is still enough to have a significant impact on care - particularly when you consider that those who are severely ill with Covid need more support from doctors and nurses than the average emergency admission.

This has a knock-on effect. For example, the number of non-emergency operations being done is still around 10% below the level it was before the pandemic began.

There's a big backlog in care

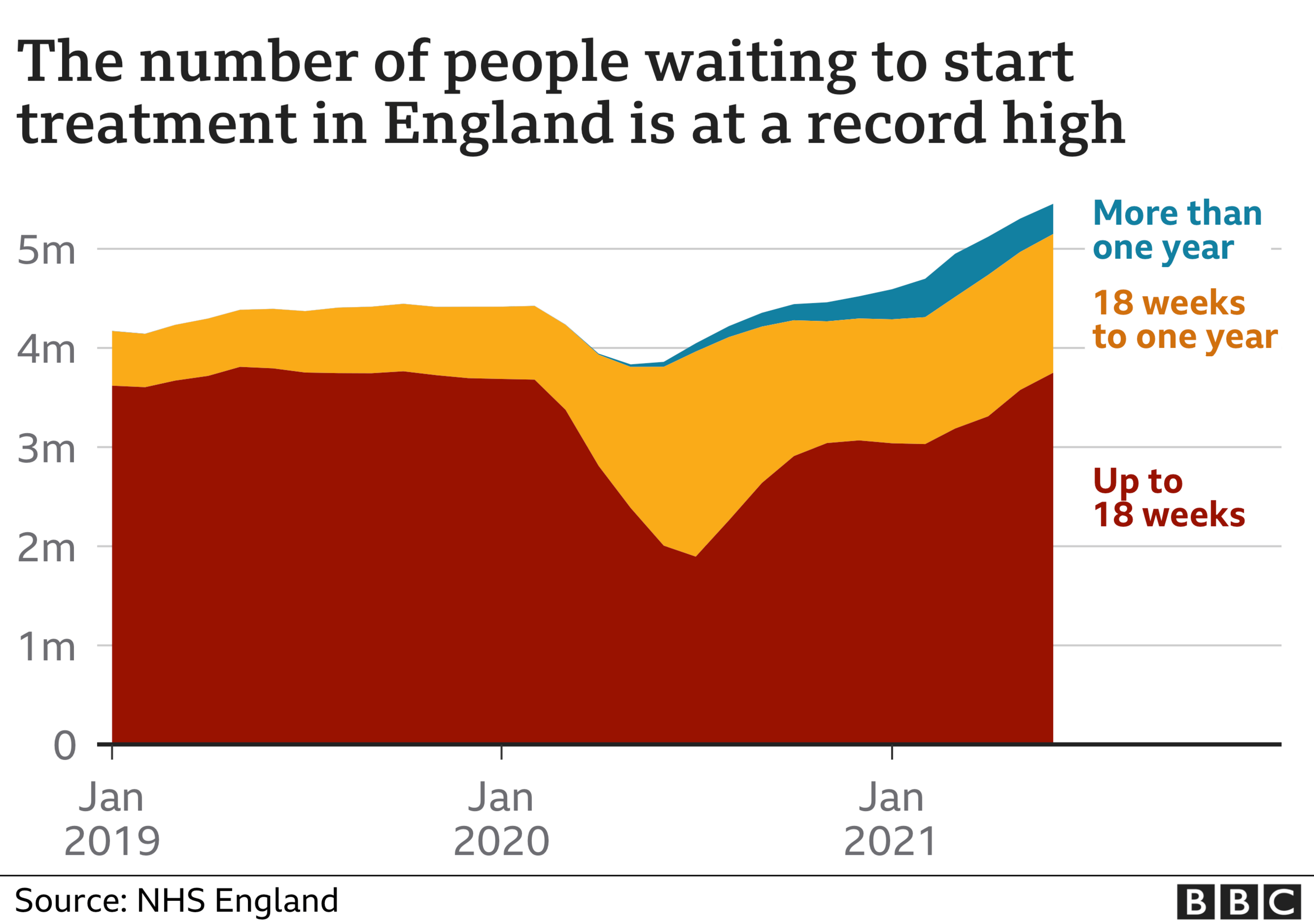

The result of this is a growing number of people who are waiting to be seen.

The waiting list of hospital operations and other routine treatments is approaching 5.5 million, the highest level on record.

And that may only be the tip of the iceberg. The number being referred for treatment in the first place has dropped significantly - in 2020 it fell by six million.

This "hidden waiting list" could soon start appearing, sending the waiting list soaring.

Cancer services have been less affected - they are seeing the numbers that were there before the pandemic.

But during the first six months of the pandemic there was a drop, meaning around 50,000 fewer diagnoses were made.

Doctors fear this could lead to a growth in people being diagnosed with late-stage cancer, which reduces the chances of survival.

The impact of the pandemic is being felt in other ways.

Mental health services are seeing a rise in people needing treatment, with reports that patients are being placed on general wards because some hospitals have run out of specialist beds.

Meanwhile, Dr Sarah Scobie, of the Nuffield Trust think tank, says "bottlenecks" in A&E and the strain on the ambulance service, mean people with severe conditions like heart attacks and strokes are waiting twice as long as expected. Performance, she says, is "deteriorating alarmingly".

The return of other viruses

Last year saw hardly any flu, while other respiratory viruses were only circulating at very low levels.

This was put down to lockdown and social distancing, meaning the normal winter viruses did not get the chance to spread.

That comes at a cost. Public Health England (PHE) has warned that immunity to these viruses will have waned, while very young children will not have been able to develop any at all.

"Children under two are at a particular risk," says PHE medical director Dr Yvonne Doyle.

There are already signs the impact of this is being felt. Rates of RSV - a virus that hospitalises 30,000 under-fives a year - are already at much higher levels than normal.

If the other viruses follow suit, the combined pressure from other respiratory viruses could exceed the current levels of Covid.

Then there is the concern that Covid cases could climb further as schools go back and people return to workplaces, and there are more normal patterns of mixing after the summer break.

What does the NHS have in the tank?

Another important consideration is the "health" of the NHS.

Unions have warned that staff are exhausted after fighting the virus on the frontline for the past 18 months.

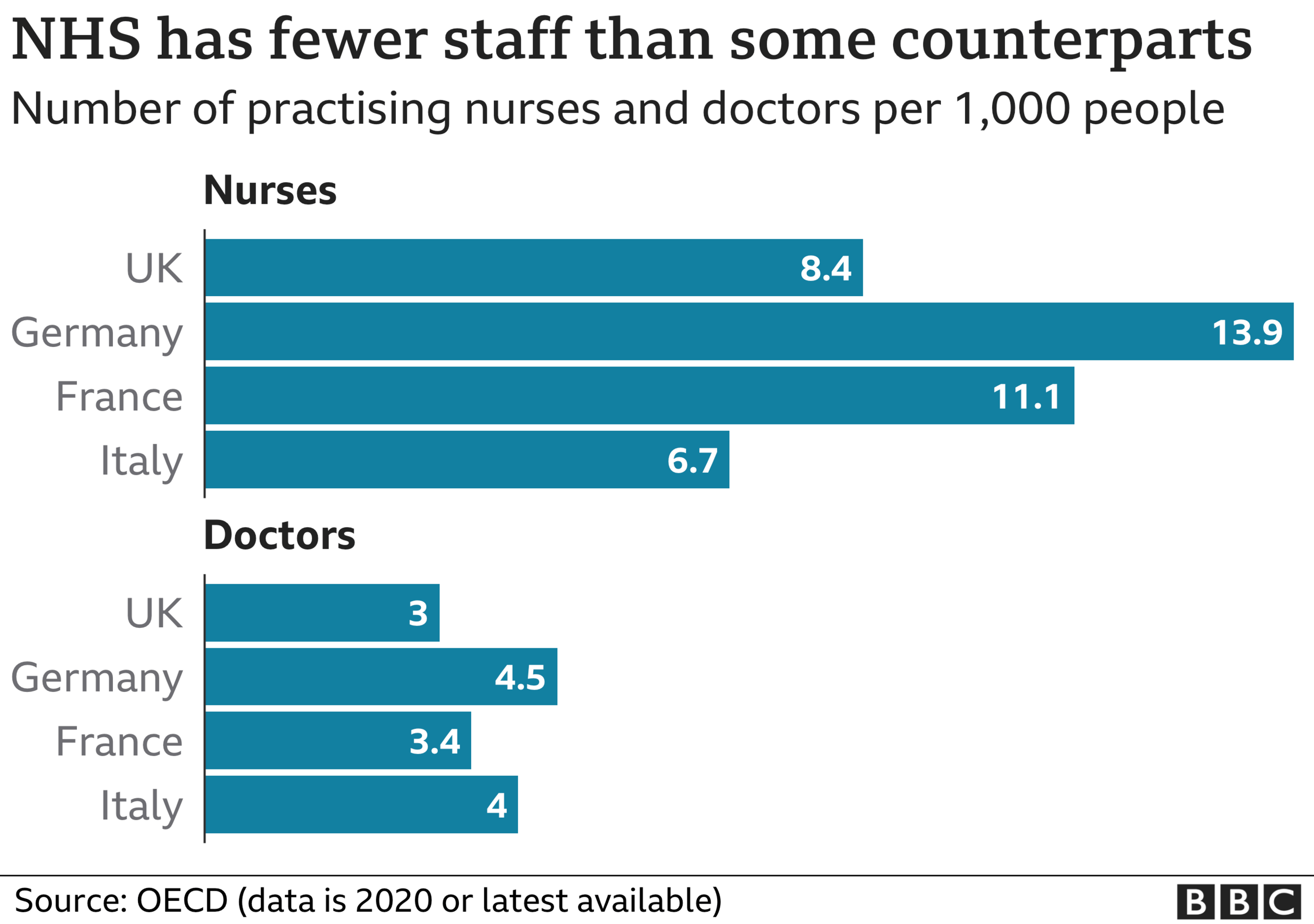

What is more, before the pandemic the NHS was already being stretched more than some of the other health systems in Europe.

The UK has fewer doctors per head than Germany and France. It is part of the reason why NHS managers in England have called for extra funding for winter, and then another £10bn more for next year on top of the £140bn they are due to get.

There is plenty of sympathy for the call.

The risk to the NHS is not just winter, says Anita Charlesworth, director of research at the Health Foundation and a former Treasury official. Covid, she warns, will be causing problems "for years to come".

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020