Lots of money for health - but what about staff?

- Published

The headline figure in the Budget and spending review was £44bn extra for health in England over the course of this Parliament.

It will mean that by 2024-25, Department of Health and Social Care spending will have risen to more than £177bn, equivalent to 4% more a year.

Much of this was already in the pipeline - spending on the NHS was already due to increase for much of this Parliament under a five-year plan agreed by Theresa May's government.

But Chancellor Rishi Sunak has topped this up with the help of the health and care levy, funded by an increase in National Insurance.

As heavily trailed in advance, there is more capital spending - to pay for equipment and new facilities - and a boost for spending on the front line from April to help cope with the extra pressure on the NHS caused by Covid. This includes a growing backlog in people waiting for operations and other non-emergency treatment.

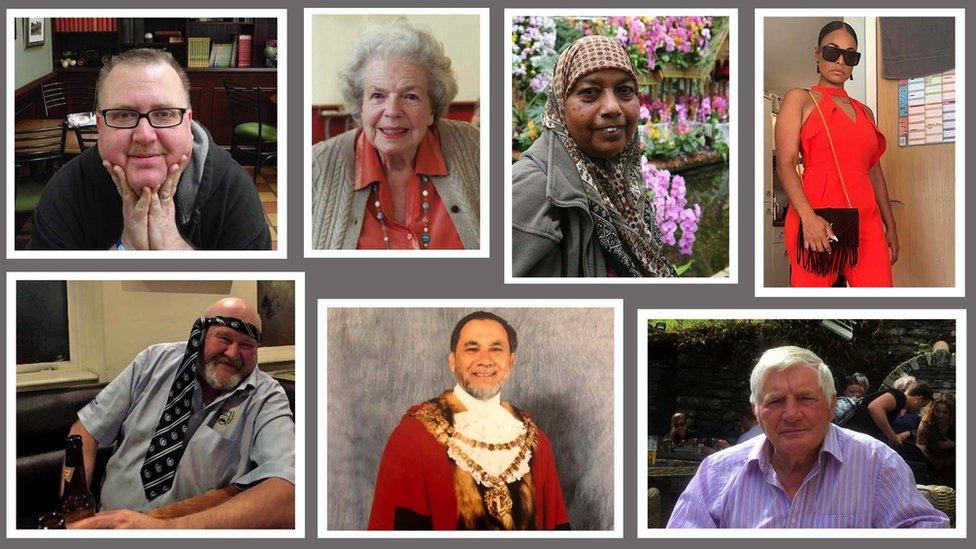

Why staffing is such a concern

But those working in the NHS still have concerns - and their biggest is that there is no clear plan for how the extra staff are going to be found to provide more care.

That's because there was no detail about spending on education and training, vital to ensure a smooth supply of new staff into the health service.

Saffron Cordery, of NHS Providers, which represents health managers, says workforce shortages are the health service's "biggest problem" at the moment.

"Shortages can only be tackled with a robust long-term workforce plan and increased longer-term investment in workforce expansion, education and training, none of which are currently in place."

There are currently more than 90,000 vacancies in the NHS at the moment, meaning 7% of posts are unfilled.

This is slightly better than it was before the pandemic began. It appears lots of staff who were due to retire put that off to work during this time, so the fear is the picture could soon start to worsen.

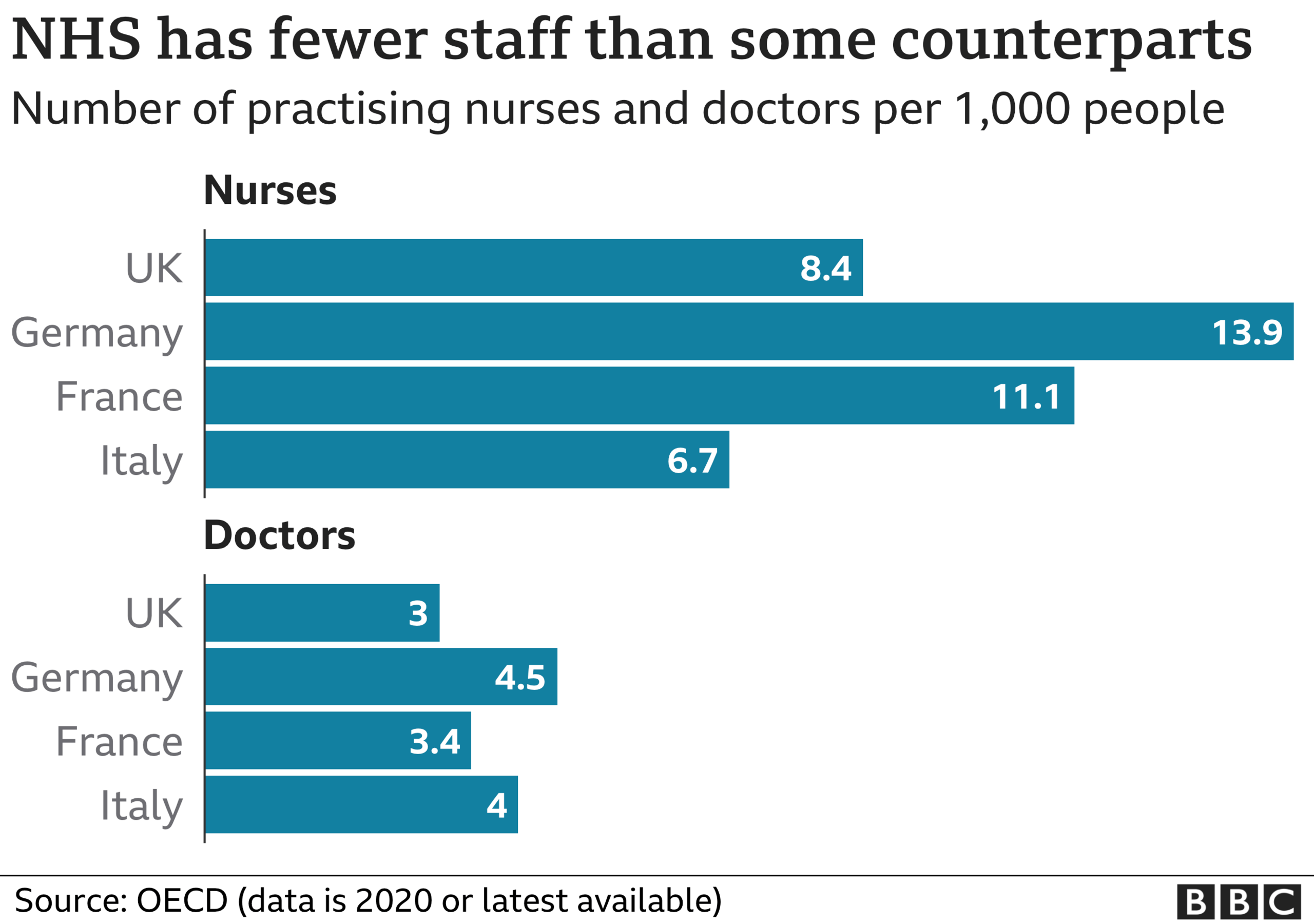

For a health system that already has fewer doctors and nurses per head than many of our Western European neighbours, that could make the government's ambitions for the NHS hard to achieve.

Social care and public health feeling the pinch

But it is not just the NHS front line where there are concerns. Earlier this year, ministers were championing their plans for social care, promising to introduce a cap on care costs, which was also going to be paid for by the health and care levy.

But that does not come in until 2023, and much of the money earmarked for social care from the levy will go on covering the costs of that rather than investing in services.

The chancellor did announce the grant given to councils to cover all services is going up, but the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (Adass) say that will be swallowed up by meeting the commitments to pay care staff more under the national living wage.

It means, says Adass vice president Sarah McClinton, there is a "real risk" people will go without vital care, suffering "indignity and harm".

Another council service that is partly dependent on funding from the overall health pot is public health.

Budgets have been cut by a quarter since 2015, once inflation is taken into account.

But the chancellor is only promising to maintain the budget at current levels, not increase it from now on.

Prof Jim McManus, of the Association of Directors of Public Health, describes this as "unfathomable".

He says the lack of extra investment will mean that vital services - from stop smoking clinics to weight management - will struggle "in the wake of the worst public health crisis of our time".

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published15 September 2021

- Published11 November 2020

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022

- Published30 April 2020