Lives at risk from long ambulance waits, say paramedics

- Published

- comments

"We have members who have been working for 20, 30 years, and they have never before experienced anything like this," said Richard Webber from the College of Paramedics (not pictured)

Lives are at risk because patients are facing unacceptably long waits for a 999 response, the College of Paramedics has told the BBC.

It comes as NHS data shows callouts for problems such as heart attacks and strokes are taking nearly three times as long as they should in England.

Targets are being missed in the rest of UK too, with some seriously-ill waiting up to nine hours for an ambulance.

Investigations are ongoing into deaths linked to delays in a number of areas.

These include:

A person died following a cardiac arrest after waiting more than five hours in the back of an ambulance outside Worcestershire Royal Hospital

A death in the East of England after it took crews an hour to get to a call classed as immediately life-threatening. The individual was found dead

With ambulance services under their highest states of alert patients are being told to make their own way to hospital where possible.

The BBC has spoken to ambulance staff across the UK about their experiences, with one saying they felt patients were at risk on every shift and another describing the situation as "horrendous".

The College of Paramedics, the professional body for the sector, described the situation as "unacceptable" and said lives were at stake.

Patients 'hugely let down'

The BBC has found reports of numerous serious incidents.

Cases involve both waits for crews to reach patients, as well as delays when ambulances arrive at A&E but spend hours queuing outside, because the hospital is too overcrowded to accept the patient.

Margaret Root, 82, waited nearly six hours for an ambulance to come following a stroke, and she then waited for another three hours outside hospital.

When she was finally admitted, her family was told it was too late to give her the drugs needed to reverse the effects of the stroke.

Her granddaughter Christina White-Smith said her grandmother had been "hugely let down".

She said she did not blame the staff because they were "amazing" when they got to her grandmother, but said she is angry the NHS is not getting the help it needs.

"I don't think people are aware of the severity of the situation."

Details have also emerged of a 66-year-old man who spent four hours lying face down on the floor at home with a punctured lung.

And in another case a man waited nine hours for help to arrive following a stroke one evening last month. His family called six times before a response finally arrived the following morning.

Ambulance service 'operating at its limits'

Richard Webber, a spokesman for the College of Paramedics and a working paramedic, said the waits patients were experiencing were "unacceptable".

"We have members who have been working for 20, 30 years, and they have never before experienced anything like this at this time of the year.

"Every day services are holding hundreds of 999 calls with no-one to send.

"The ambulance service is simply not providing the levels of service they should - patients are waiting too long and that is putting them at risk."

He said the delays in handing patients over to hospital staff were causing havoc.

Mr Webber said waits of three or four hours were not uncommon.

"It means on a 12-hour shift we can only attend two or three incidents, whereas previously we would do six, seven or eight," he added.

His evidence is supported by data collected by the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, which shows the number of hours lost to handover delays lasting more than an hour, is now more than twice as high as it was in January.

The impact on response times is clear. The latest data for October shows in England category one cases classed as immediately life-threatening, such as cardiac arrests, took more than nine minutes on average to reach.

The target is seven minutes and research shows every one-minute delay reduces the chances of survival by 10% for cardiac arrests.

Category two cases cover emergencies including heart attacks, strokes and burns. They are meant to be reached in 18 minutes on average, but took nearly 54.

Response targets are also being missed in other parts of the UK.

In Wales, the Healthcare Inspectorate recently warned delays were presenting a risk to patients.

Shortly afterwards the ambulance service there requested help from the military.

The system is 'severely stretched'

There appear to be numerous reasons behind the problems.

There are also signs that the pandemic and the disruption it has caused to health care and everyday life, has meant the health of frail and vulnerable people has deteriorated, leading to more demand on services.

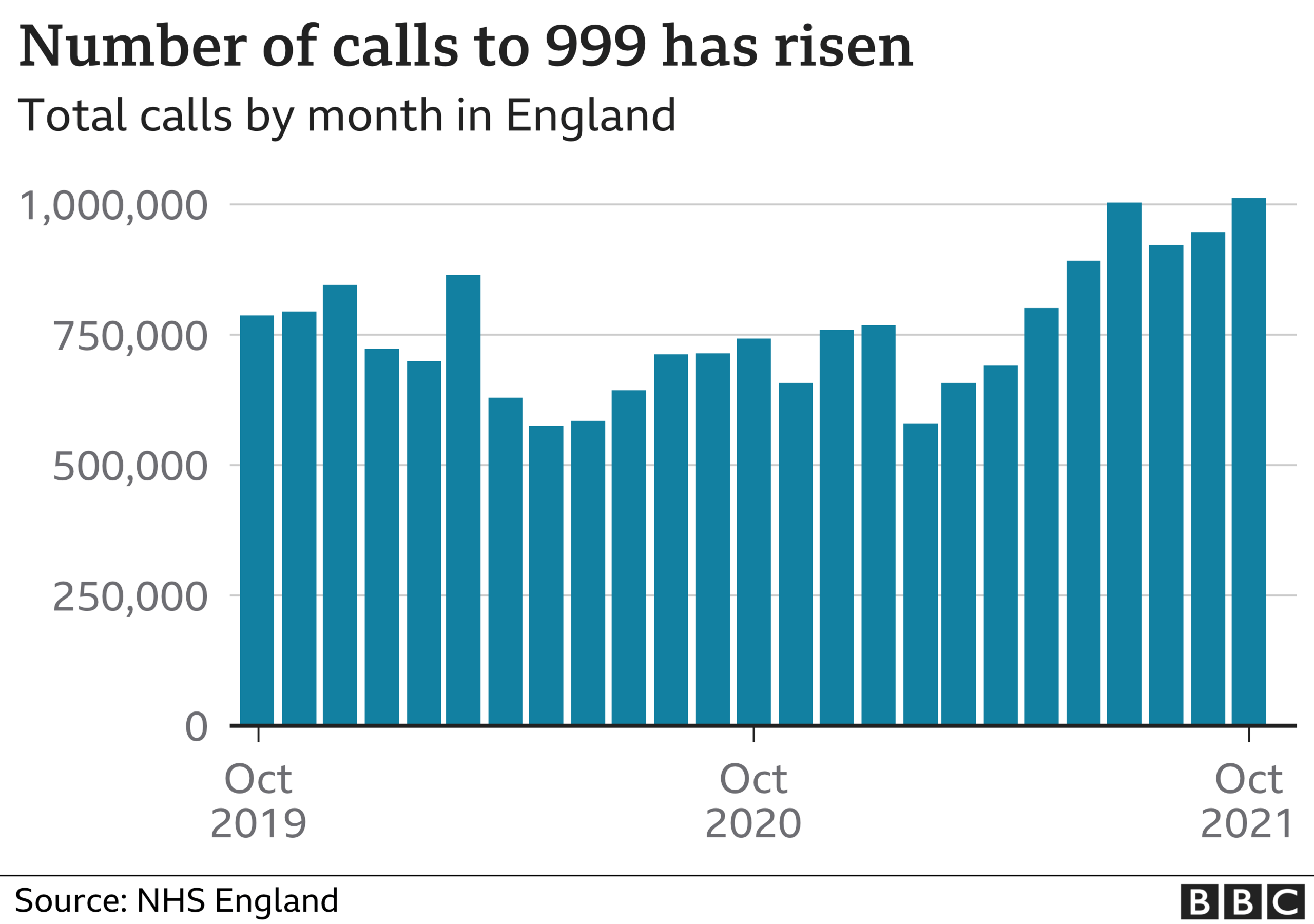

Calls to the ambulance service are up by around a quarter on the numbers seen before the pandemic.

Hospitals are also reporting problems trying to discharge patients who are medically fit to leave but cannot because there is no social care available to support them in the community.

This is causing significant delays admitting patients onto wards, and in turn is leading to long waits for ambulance crews arriving with patients.

The head of the Scottish Ambulance Service, Pauline Howie, recently made an apology to the public, describing the pressures being faced as "unprecedented".

Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents both ambulance and hospital bosses in England, said the system was "severely stretched".

"What is worrying now is that they are all operating right at their limits and we are not yet into winter, when there's every chance these pressures could step up still further."

Prof Stephen Powis, medical director of the NHS in England, praised the work of staff, saying they were going "above and beyond".

He pointed out the ambulance service had had to deal with the highest number of 999 calls ever in a single month, while major A&E's had experience their busiest October.

"There is no doubt pressure on the health service remains incredibly high."

Additional reporting by Tim Vizard and Katherine Roberts

Related topics

- Published24 September 2021

- Published14 July 2021