NHS spending: How much money does it need?

- Published

Luke's passion is football

A new drug Kaftrio, now available on the NHS, has made a huge difference to patients like Luke Copsey who has cystic fibrosis.

Its list price is a mind-blowing £100,000 per year, although the health service has negotiated an undisclosed discount with the manufacturer.

For Luke, the tablets are priceless.

"Now I can go and do whatever I want in my life rather than thinking life is running away with me," the 23-year-old explains.

Luke inherited his life-threatening condition and struggled for years, despite being on various medications.

"I was having to tell friends, I can't come out because of medication I had to do, or if I did go I'd have to leave after an hour and they'd all be having fun. You're physically unwell really constantly," he says.

"Within three weeks of being on Kaftrio, my lung function leaped from 55% to 80% capacity, which is just an unimaginable jump. I went from not being able to breathe and thinking 'oh, this is just what life's like', and after taking it just thinking 'oh, this is what it's really meant to be like'."

Luke, who is an outdoor activity instructor, says he is taking advantage of his new-found energy and lung power. He can now play a full game of football instead of being forced to throw in the towel after just 10 minutes.

But his case is a good example of how the health service continues to face higher cost pressures than the rest of society.

Luke climbed to the top of Snowdon a few months ago

How does the NHS afford it?

Nobody would want patients like Luke to be denied access to a medicine that can make such a difference to their lives. But with finite finances, who should get what for free?

Cost-effectiveness of NHS treatments is assessed by the regulator National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England, and it is left to the devolved administrations to make their own decisions.

Expensive new therapies are coming on stream in increasing numbers.

A recent example is a cancer game-changer called CAR-T therapy, approved by NICE. It is a form of immunotherapy which involves collecting and using the patients' immune cells to treat their condition. A single intravenous infusion has a list price of £282,000 although, again, the pharmaceutical company has agreed a discounted price.

It shows how really hard choices are being made by regulators and NHS leaders - choices that will decide whether sufferers of a variety of different illnesses can have a good quality of life.

The government at Westminster announced a National Insurance increase - branded a Health and Social Care Levy - to pay for higher spending on the NHS in England. Chancellor Rishi Sunak says some of this will fund a plan to clear the backlog of cancelled operations.

But the big question is whether planned spending increases will be enough?

Growth market

Demographics play a huge part in the longer term funding needs of the NHS. A population which is growing and getting older will inevitably need more healthcare. Simply put, more years of life will mean higher demand for NHS services.

The Office for National Statistics predicts the UK population will increase by three million between 2018 and 2028. A higher proportion will be aged 85 and over, and some of these will need costly care.

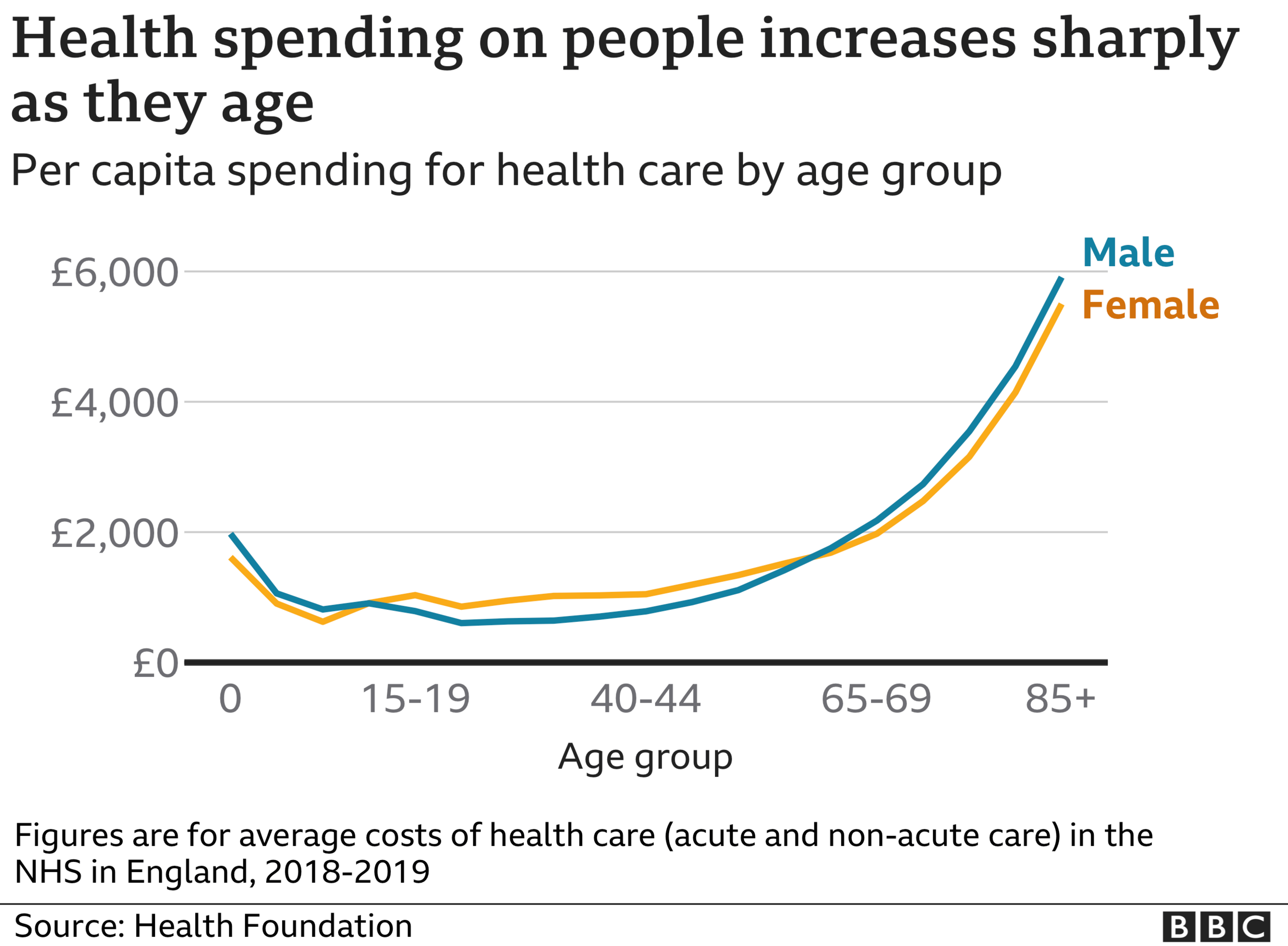

Analysis by the Health Foundation think tank suggests the average bill of healthcare for men and women increases rapidly from the age of 45.

Factors like this explain why the health service in the longer term tends to require annual funding over and above economy-wide inflation.

Spiralling costs

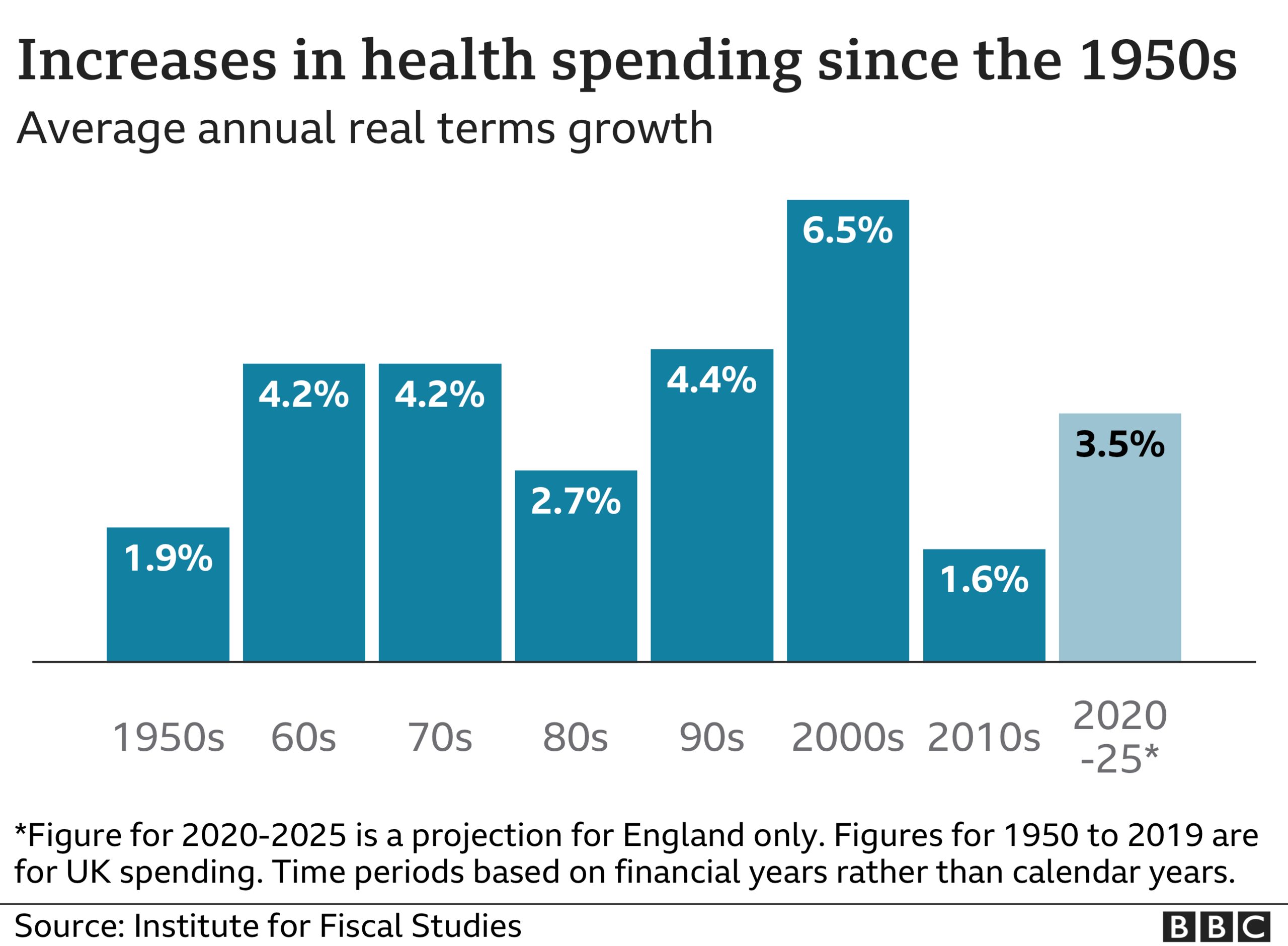

Since the early years of the NHS, the government of the day (now Westminster and the devolved administrations) has always been under pressure to find more money to keep up with healthcare innovation and population change.

Average annual UK health spending in real terms rose by more than 4% in the 1960s,70s and 90s. It went up to 6% in the 2000s.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates planned health spending in England will rise by an average 3.5% per year up to 2024-25. Proportionate increases will go to the governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, although they are not obliged to spend that money on health.

The chancellor described it as a "game-changing investment" - but it has been made clear in return the Health Service must demonstrate greater efficiency.

The Treasury's focus on value for money was clear, with an intervention delaying the NHS plan.

It has always been suspicious of annual demands for extra cash from health service leaders and lobbyists, particularly as other departments have been squeezed to allow the NHS more financial headroom.

But the 3.5% projected increases in England are still below the 4% historical trend. And some of them will be required to cover ongoing Covid costs. Added to that is the task of tackling the backlog of operations and surgical procedures, future workforce training and coping with new demand. Seen in that light, the idea of "generous" increases for the NHS is questionable

People who have waited a year or more for operations want them done. The NHS, like the rest of society, will have to live with Covid and adapt.

For Luke there is no question that being put on new medication has transformed his life. He says: "I'm not spending literally months and months and months of the year in hospital, I'm now able to achieve my dreams, which previously wouldn't have been possible."

Related topics

- Published6 September 2021

- Published2 September 2021