Is this NHS crisis really worse than ones before?

- Published

The headlines were terrifying. Hospitals facing intolerable pressures with patients left dying in corridors, the BBC reported.

It got so bad that 68 leading A&E doctors wrote to the prime minister to spell out their concerns.

This is not now though. It was the winter of 2017-18 - the last bad flu season when more than 300 people a day were dying from that virus at one point.

And that was not even a one-off. In January 2016 hospitals were cancelling routine operations, telling patients to stay away from A&E if they could, and emergency treatment areas were being set up outside some units - just as they are now.

The truth is the past decade has been a story of lengthening waits and declining performance.

A&E waits are the best barometer of this. The proportion of patients waiting less than four hours - a key metric in measuring NHS effectiveness - has been gradually eroded.

It is a similar story elsewhere in the UK - with performance even worse in Wales and Northern Ireland.

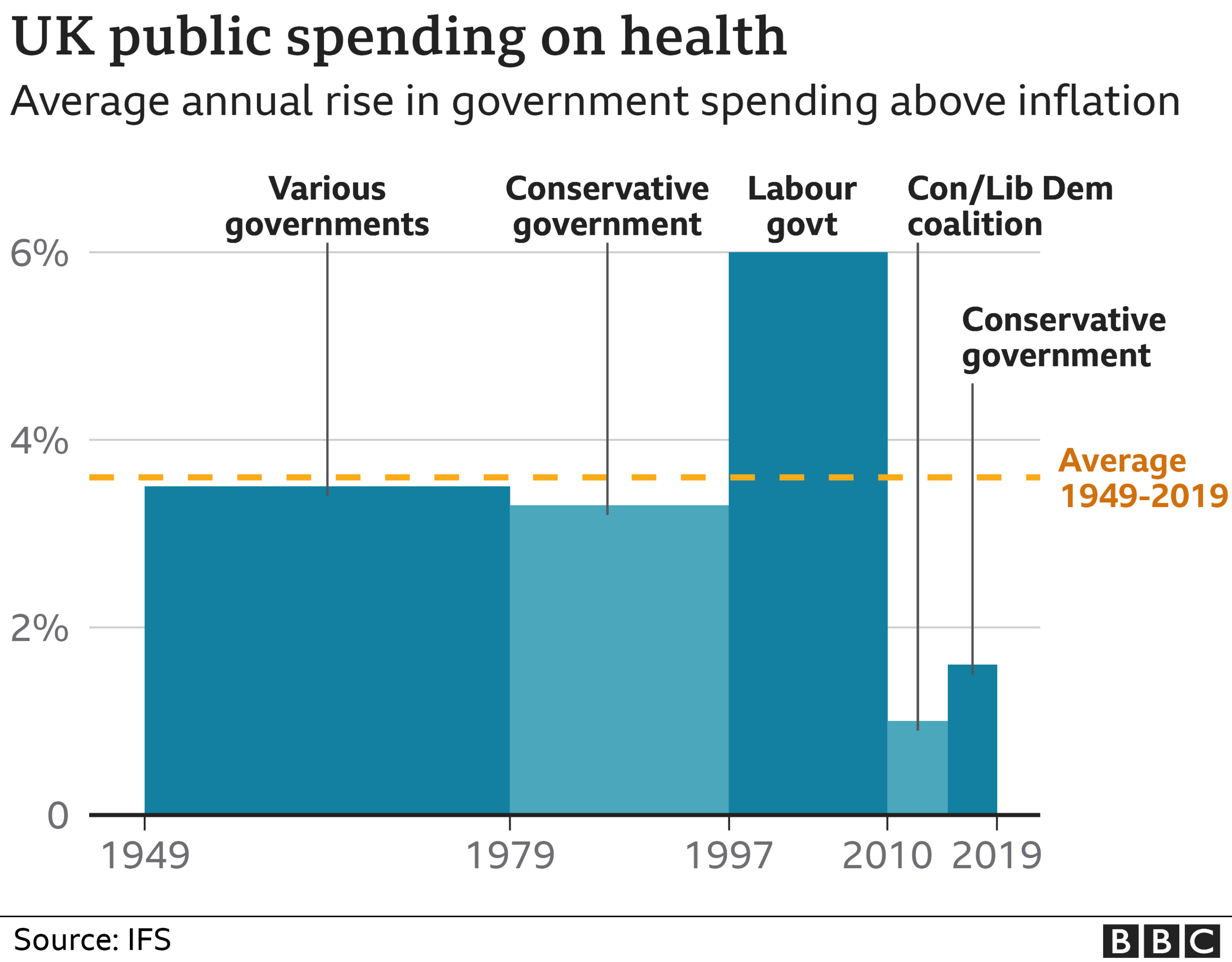

This should not come as a surprise, as NHS spending has been squeezed.

Between 2010 and 2019 the annual rises for health were well below those traditionally given since the birth of the NHS, making it difficult to keep up with the needs of the ageing population.

During that period, the Tories have been in power - albeit with the Lib Dems for the first five years.

But it is worth noting, in its 2010 and 2015 election manifestos, Labour was not proposing any tangibly higher increases in spending either.

The financial crash of 2008 meant all the main political parties were signed up to the idea that spending had to be curtailed.

This parliament has seen a change - annual rises are now planned to be close to 4% and will end up higher once the pandemic spending is taken into account.

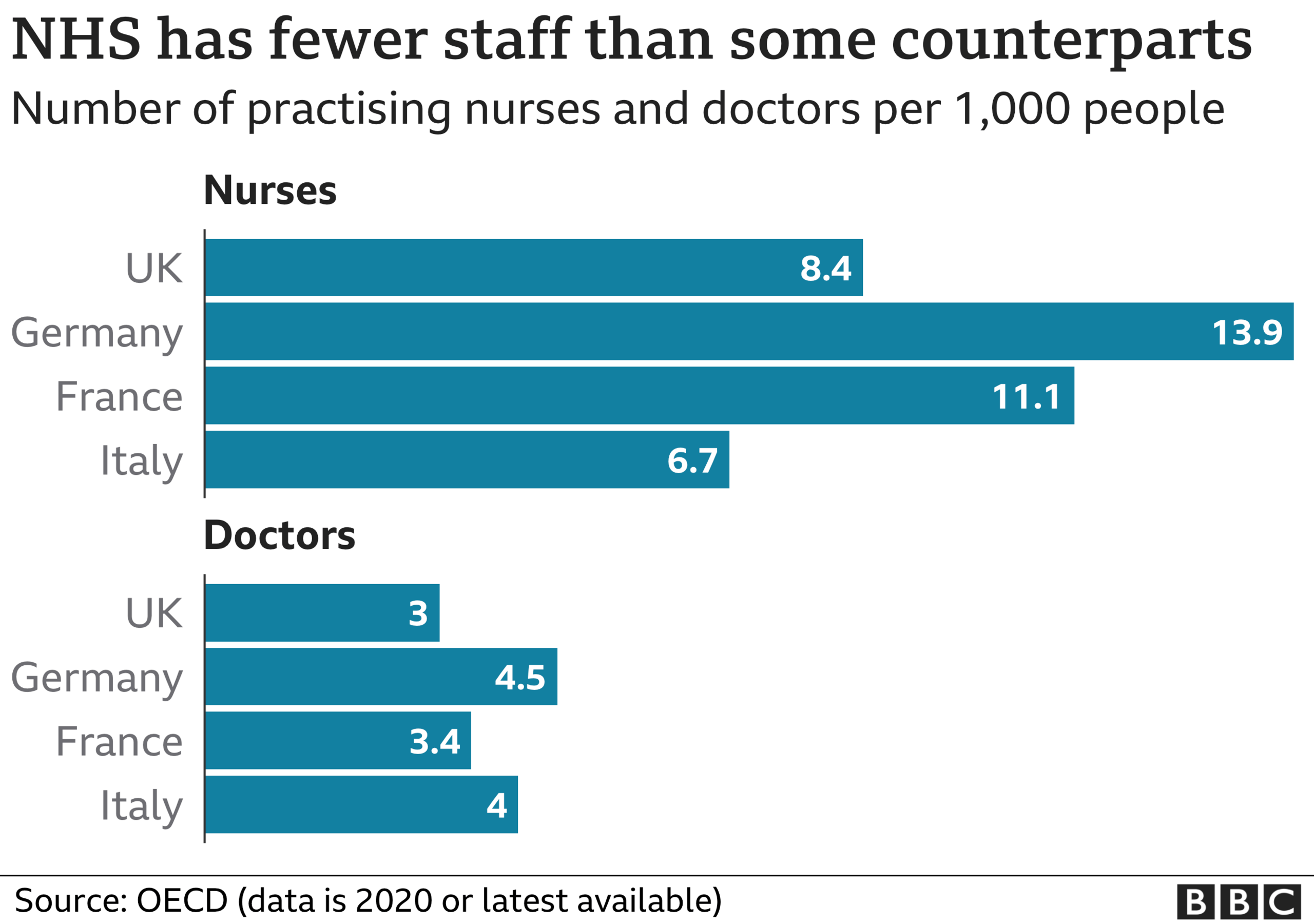

But the result of the squeeze in the 2010s is fewer doctors and nurses per head of population than our Western European neighbours.

The turn of the year is always the hardest time. And with the latest data for A&E only covering November, we need to look elsewhere to judge how alarming the current pressures driven by the Omicron variant are.

Since Christmas there have been reports of hospitals declaring critical incidents. At one point on Wednesday evening, one in seven hospital trusts in England were in this situation.

It is, however, very hard to judge exactly what these declarations tell us. They are not normally made public and instead are there to alert local health systems that a service needs help. We have nothing to compare them to.

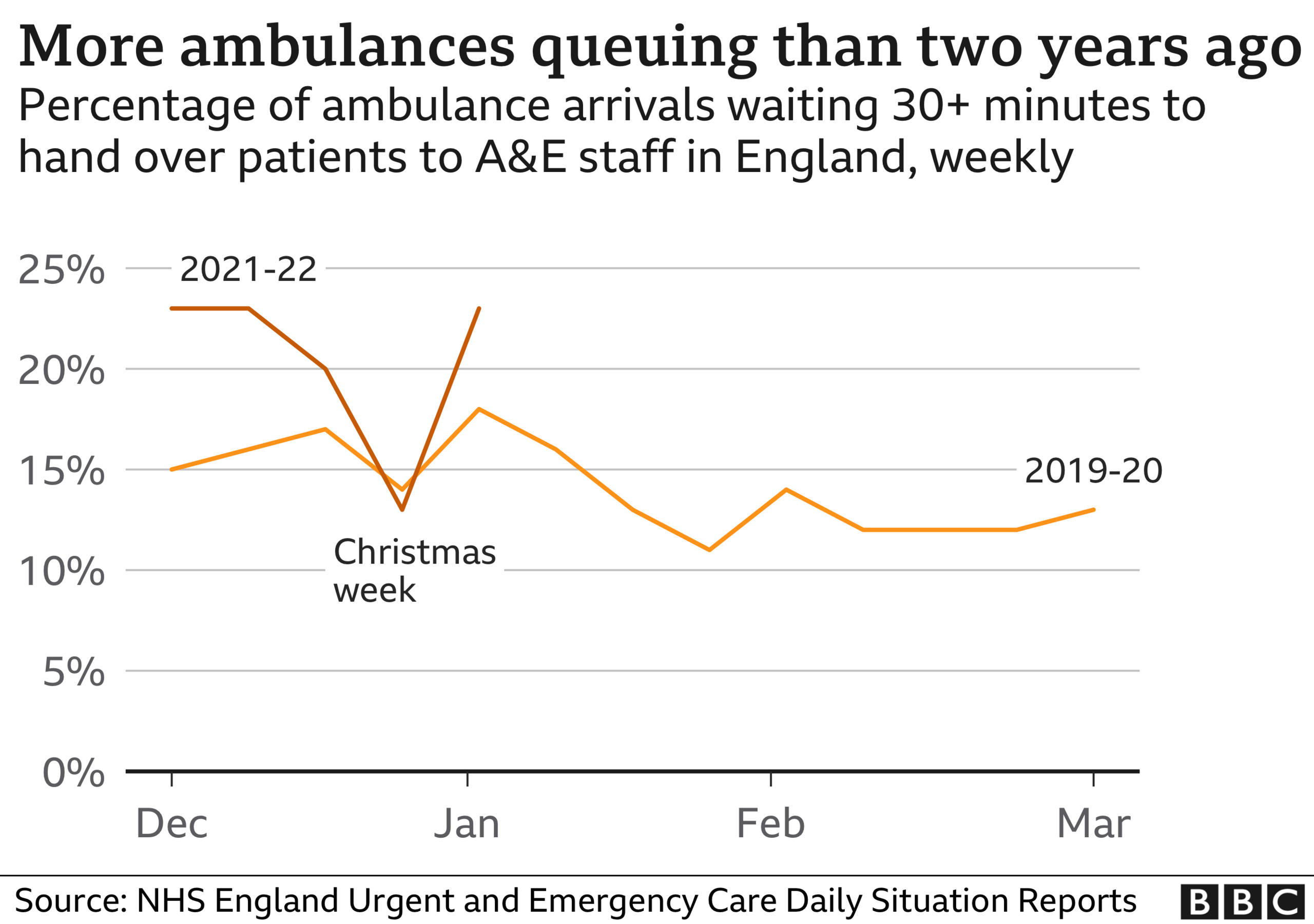

If we look at the delays ambulances face when dropping off patients at A&E - this data is available in England up to last weekend - we can see the current difficulties are worse than the last winter before the pandemic hit.

But it is also fair to say this does not represent the collapse of the NHS, despite all the headlines.

The truth is the health service will not suddenly become overwhelmed. Instead, what is happening is that care is deteriorating bit by bit.

The heart attack patients are waiting longer for an ambulance, more elderly patients are spending nights on a trolley in A&E and growing numbers of people are waiting for hip and knee replacements.

The challenges are, of course, different from winters past. It is a pandemic after all.

A mass vaccination campaign is underway, while the level of staff absence from Covid is bringing another added complexity - it is nearly twice what you would expect - and explains why the army has had to be brought in.

Hospitals have also had to completely reconfigure their wards to create Covid and non-Covid areas.

And the sheer numbers coming in are a problem. Traditionally winter would see around 1,000 admissions a day for all types of respiratory infections.

Currently the NHS is seeing more than double that for Covid alone - although a chunk admittedly are people who are ill with something else, such as broken arms, strokes and cancer for example, and may well have come in anyway.

But even if you discount these patients, you are still well above the 1,000 threshold.

However, the NHS has been helped by lower pressures elsewhere. Flu is at rock-bottom levels. There are fewer than 50 patients in hospital with the virus in England.

So what can we conclude? The challenges are certainly worse and that is translating into poorer quality services.

But this is not the first year care has been compromised. What matters now is when Covid infections peak - that will determine just how bad this winter will be.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

Read more from Nick

Has your NHS treatment been delayed? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022