Surgical mesh centres not working, warn MPs

- Published

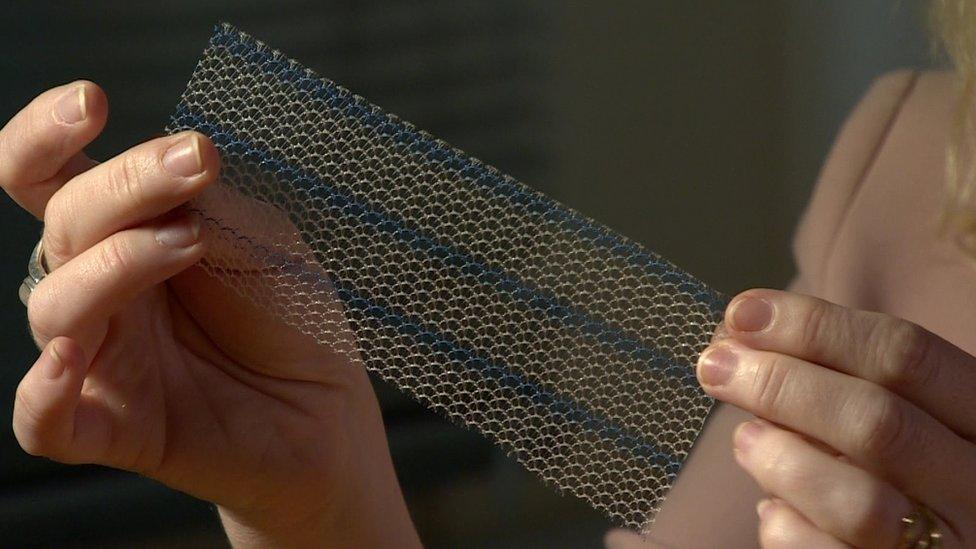

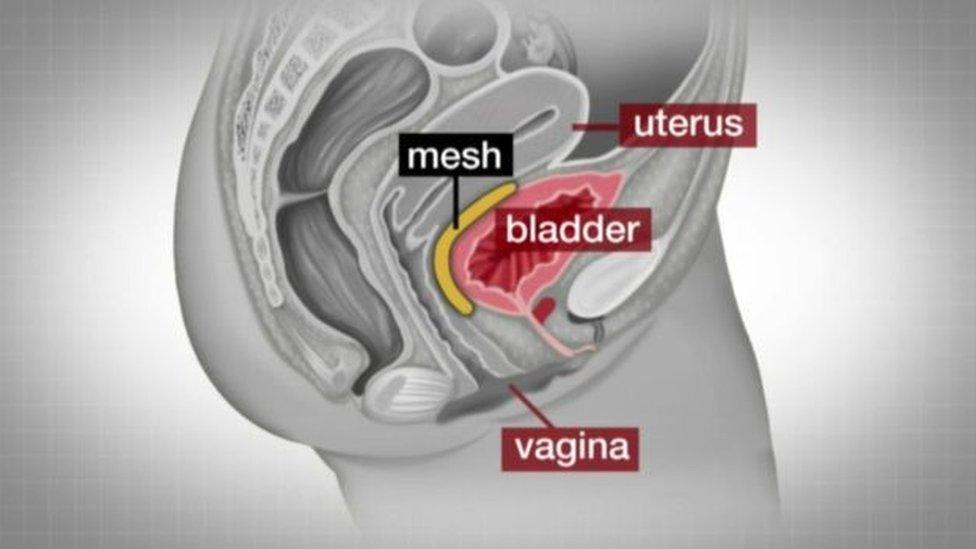

The mesh implants are used to ease incontinence and support organs

Specialist centres to help women who have experienced complications following a pelvic mesh repair are "not working", MPs say.

A network of nine mesh centres was set up in the wake of a report about how three health treatments caused thousands of women avoidable harm.

However, a debate in Westminster Hall has heard that GPs are not always aware of the referral process.

And some patients are experiencing long waits and living in "agony".

'Gaslighting and suffering'

More than 100,000 women are thought to have had a mesh repair to treat pelvic organ prolapse or incontinence before this treatment was paused in 2018.

The procedure rarely happens in much of the UK currently and has been completely halted in Scotland.

Complications include chronic pain and mesh erosion, where the device cuts through tissue and perforates organs.

A group of cross-party MPs has shared stories detailing how mesh has cost women their jobs, mobility, relationships, sex lives and freedoms.

The mesh is made of a polypropylene, a type of plastic

In 2020, the First Do No Harm report recommended specialist mesh centres should be set up to treat complications and carry out removals.

There are now eight centres in England and one in Glasgow, and the Welsh government says it's considering setting up one.

However, Alec Shelbrooke, co-chair of the surgical mesh all-party parliamentary group, has told MPs the centres are "not working".

"GPs are unaware of mesh complication centres and the referral process," he said

"Many patients are denied access and are offered physio and pain management instead, they pay thousands of pounds for private care and face extremely long delays for appointments.

"Many women end up seeing their implanting surgeons, who then dismiss them."

Sharing accounts of women's experiences, Mr Shelbrooke said one waited four years for a referral only to face more "gaslighting" and "suffering".

Another was told her mesh was too dangerous to remove, and she was left in "agony".

The debate heard there are only a "handful of people" who specialise in mesh removal, which is likened to extracting hair from chewing gum.

Health minister Maria Caulfield said she needed to know if centres weren't meeting women's needs.

In July 2020, the Baroness Cumberlege review concluded the health service did not listen to women who reported concerns relating to pelvic mesh repairs and hormone pregnancy tests, which have been linked with birth defects and miscarriages.

The report also looked into the anti-epilepsy drug sodium valproate, which can increase a baby's risk of developmental disorders and physical abnormalities if taken during pregnancy.

A central recommendation was financial redress for those affected by these three health treatments, but so far the government has refused, with funds focusing on "improving future medicines and medical devices safety".

MP Sarah Green says offering financial support is "the right thing to do" and has urged ministers to reconsider.

"Baroness Cumberlege and her team met with over 700 affected individuals, mostly women," she said. "They found that they were not being listened to by medical professionals. Now they're not being listened to by their own government."

Theresa May, who commissioned the review when she was prime minister, agreed: "The longer it takes to fully implement the recommendations, the more rejection these people are suffering every week that goes by."

The government says it has accepted the "majority" of the review's recommendations, including appointing a patient safety commissioner, while the Scottish government will also appoint one.

Related topics

- Published8 July 2021

- Published9 July 2020