How the NHS wrestled with worst winter on record

- Published

This has, on nearly all measures, been the most difficult winter for the NHS in a generation.

Services have been overhauled, but patients have still had to wait longer for treatment and care has suffered as a result. Can we expect the pressures to start easing soon?

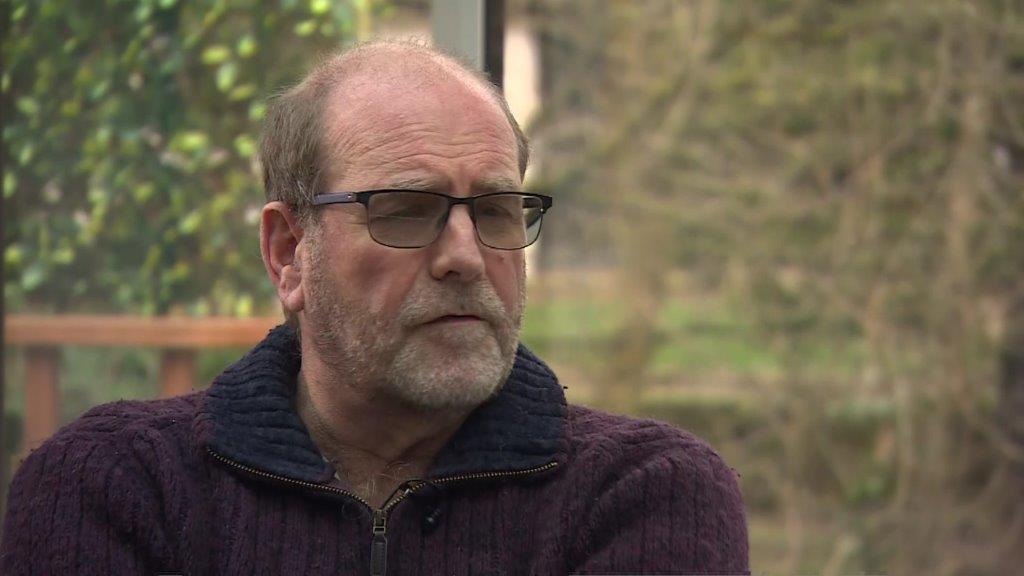

Dr Wesley Vernon still needs more surgery

Retired doctor Wesley Vernon was told he needed to have cataract surgery on both his eyes in late 2019.

Combined with his Parkinson's disease, his failing eyesight was having a major impact on his day-to-day life.

But before he could get treated, the NHS cancelled all routine treatments to cope with the first wave of Covid.

By the time services resumed in late spring 2020 a huge backlog had started building and he found himself pushed further and further back on the waiting list.

His eyesight worsened and he started to have falls and accidents.

'My life is on hold'

He finally had the first cataract done last October - after two years of waiting - but has still not had his other eye operated on.

He is now desperate. "I want to make the most of the time I have before my Parkinson's get worse."

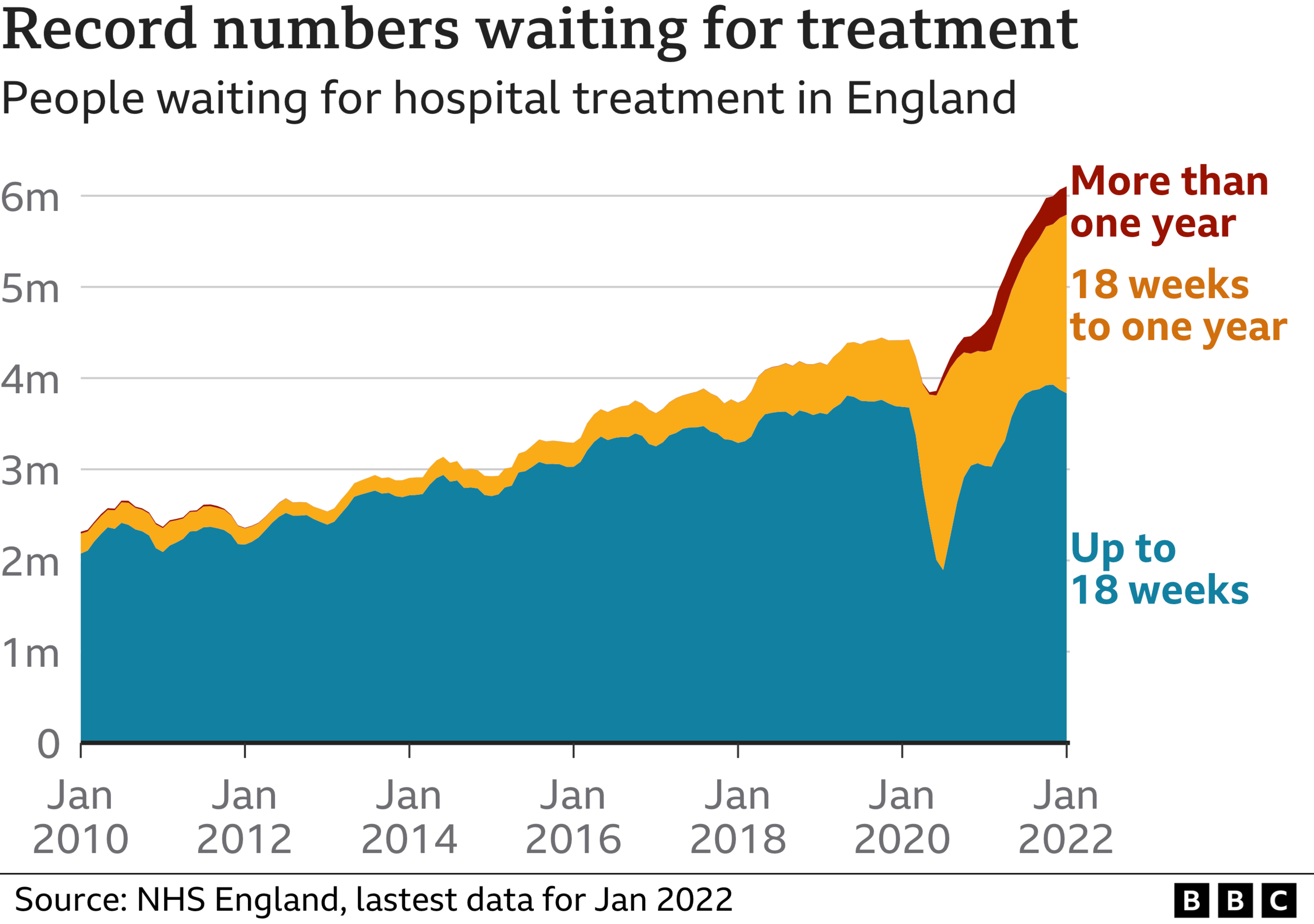

Dr Vernon's story is not unique. More than 6 million people in England are on a waiting list for hospital treatment - that's one in nine of the population.

Over 300,000 of them have waited over a year as the NHS has struggled to cope with the demands of dealing with Covid alongside its normal workload.

Since the start of the pandemic, nearly 750,000 patients with Covid have been admitted to hospital.

At points, the number of admissions has been four times higher than what would normally be seen for all types of respiratory illnesses combined.

It has put huge strain on the service. Even this winter - with the Omicron wave proving milder than many feared - the numbers were still double.

Performance at worst level for generation

As a result, hospitals have seen waiting times deteriorate across the board - not just for non-urgent work like cataracts.

Wherever you look, delays worsened - in A&E, across ambulances services and in cancer care too.

Performance in recent months has been at its worst level since modern-day targets were introduced in the early 2000s.

Although it is fair to say the last decade has been a story of declining performance, winter coupled with the complications of Covid has exacerbated that trend.

This is not unique to England. As has been documented by the BBC's NHS Tracker project, other parts of the UK have been struggling too.

If you can't see the look-up, click here.

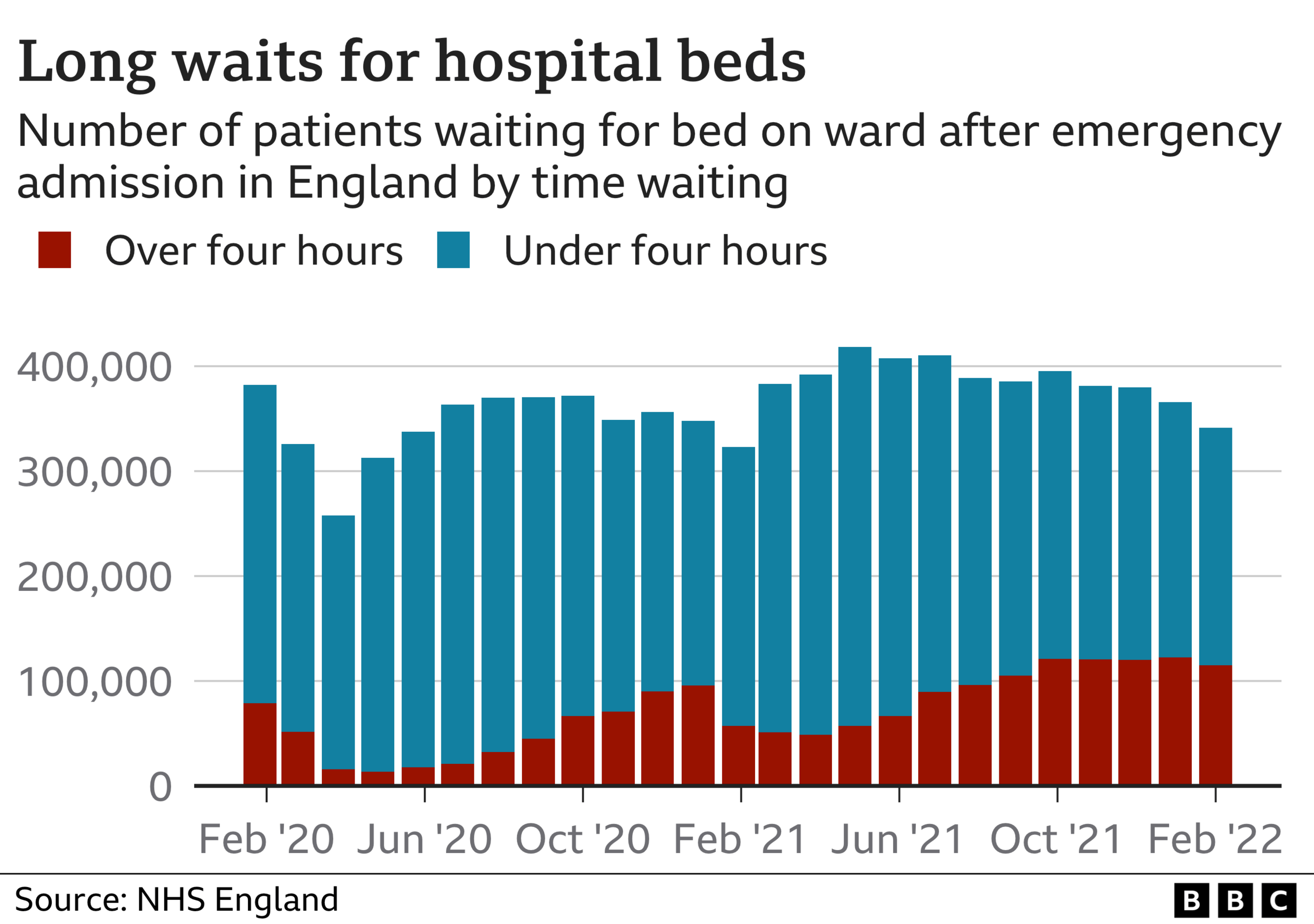

Perhaps one of the clearest examples of how the system has struggled can be seen with what is happening when patients need to get admitted to a ward.

These are the sickest patients, but instead of being found a bed quickly, increasing numbers have spent hours waiting on trolleys and in cubicles because there is no spaces on the wards.

This puts patients at risk. Royal College of Emergency Medicine president Dr Katherine Henderson says staff have been finding it "harder and harder" to look after patients.

"There is a shortage of beds which is leading to delays and dangerous crowding. Every metric shows performance continues to deteriorate. With no light at the end of the tunnel, morale is very low."

There are many complex factors that are playing a role in this - staff shortages, a lack of care in the community, which means patients discharge from hospital is delayed, and the fact that running hospitals has become more difficult because of the infection control measures needed to combat Covid.

To cope, the NHS has overhauled services. Hospital sites have been reconfigured and the way services work has been overhauled.

Covid-free sites have been set up and planned surgery moved to different locations.

One model being increasingly used is surgery hubs, whereby hospitals share resources.

'We've broken down barriers'

This has been pioneered by a number of areas, including Epsom Hospital in Surrey.

It acts as a regional hub for orthopaedic treatments, such as hip and knee surgery, for south west London and the nearby suburbs.

Staff from other hospitals work at the hub and patients come from all over the region to get their treatment.

At one point, the hub was operating on patients every day of the week.

Other steps are also being taken. For example, follow-up appointments post-surgery are no longer being done in-person routinely and pre-operation assessments are, where possible, done at the same time as a patient is diagnosed, reducing the need for repeat visits.

This has proved particularly successful for operations such as cataract surgery, which is normally straightforward and does not require overnight stays.

The waiting times in this area of the country are returning to normal.

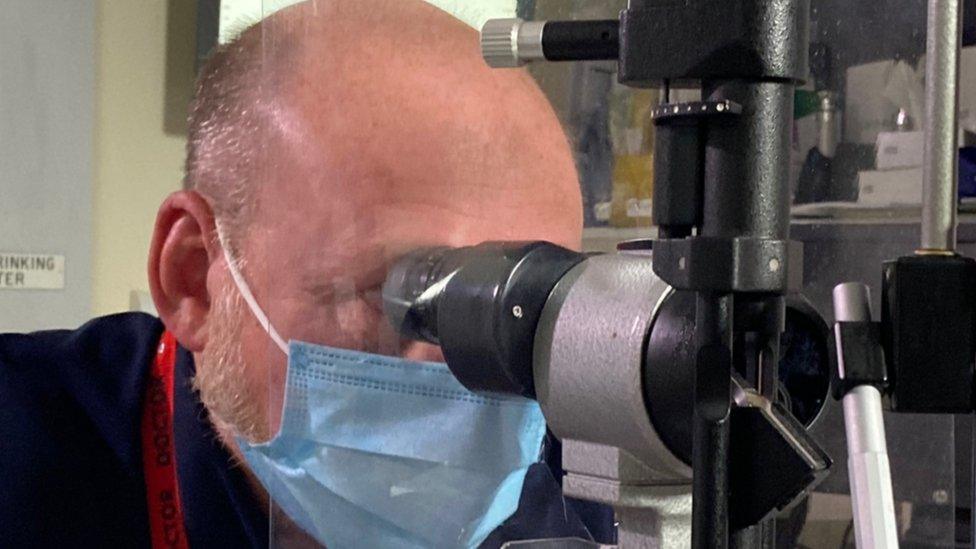

Paul Ursell has helped pioneer changes to the way cataract surgery is organised

Ophthalmic surgeon Paul Ursell says: "We've broken down some of those barriers - we've had to. Waiting for treatments such as cataract surgery has a huge effect on people - they can get depressed, they are more likely to fall, they stop going out and lose their confidence."

The success Epsom has had offers hope to Dr Vernon and others that as the model gets adopted elsewhere the backlogs will be tackled.

It is a huge challenge that will take time though. Ministers have warned the numbers waiting for treatment are likely to grow before they start falling. It could be March 2023 before the trend reverses, they have warned.

Winter maybe ending, but for the NHS the hard work continues.

Data analysis by Christine Jeavans and additional reporting by Chloe Hayward

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022