NHS faces an Easter 'as bad as any winter'

- Published

NHS leaders are warning that the health service is facing the "brutal reality" of an Easter as bad as most winters.

Latest data shows record waits for planned surgery and in A&E, as staff plough through a backlog fuelled by Covid. The government says there is hope on the horizon.

Retired seamstress Jean Shepherd had a stroke in April last year, leaving her severely disabled and requiring round-the-clock care.

At the end of February there was an outbreak of sickness at her nursing home and she needed hospital treatment.

She had to wait in a wheelchair for more than 9 hours until an ambulance arrived to take her to A&E.

The 87-year-old from Nottingham then spent the next 31 hours on a trolley between the emergency department and a secondary-care unit.

"She was very distressed because she doesn't like hospitals at the best of time," says her son, Andy Shepherd. "Since the stroke, because of her cognitive ability, she doesn't understand what's happening around her."

Mrs Shepherd was eventually moved to a bed in a main hospital ward, where her family says she later contracted Covid, before recovering and being discharged back to her care home two weeks later.

"I appreciate that A&E departments have always been busy, but I just wasn't prepared for what greeted me at the hospital," says her son.

"There were patients on ambulance trolleys literally everywhere and the staff were absolutely rushed off their feet. I remember thinking at the time that this is not sustainable."

Nottingham University Hospitals Trust has apologised for the delay in admitting Mrs Shepherd to a ward, saying she received "expert care" in the emergency department while staff were dealing with an "unprecedented level of demand".

Jean Shepherd back in her care home after hospital treatment

'Never as bad'

That kind of 31-hour wait might be at the extreme end.

But nationally, it's in emergency departments that the pressure on the NHS is most visible at the moment.

The number of people arriving at A&E has been increasing steadily over the past decade, driven in part by a growing and ageing population.

Over the past year the proportion having to wait a long time to be treated has been rising to record levels.

In March, external, just 71% of patients were seen, treated and then admitted or discharged in under four hours, compared with 87% in March 2019 - the year before the pandemic began.

Over the past few weeks, hospitals from Liverpool to West Yorkshire to Nottingham have had to post warnings online asking the public to think twice before turning up at A&E if they did not need urgent or life-saving care.

"I have never seen it as bad as it is now," says Dr Katherine Henderson, the RCEM's president. "Long waits in emergency departments cause harm because a patient's condition may deteriorate and there may not be the staff there to notice.

"It makes everybody really anxious, and we know that people are not getting the care they deserve."

This problem is not unique to England. A&E waiting times in other parts of the UK have been increasing, too.

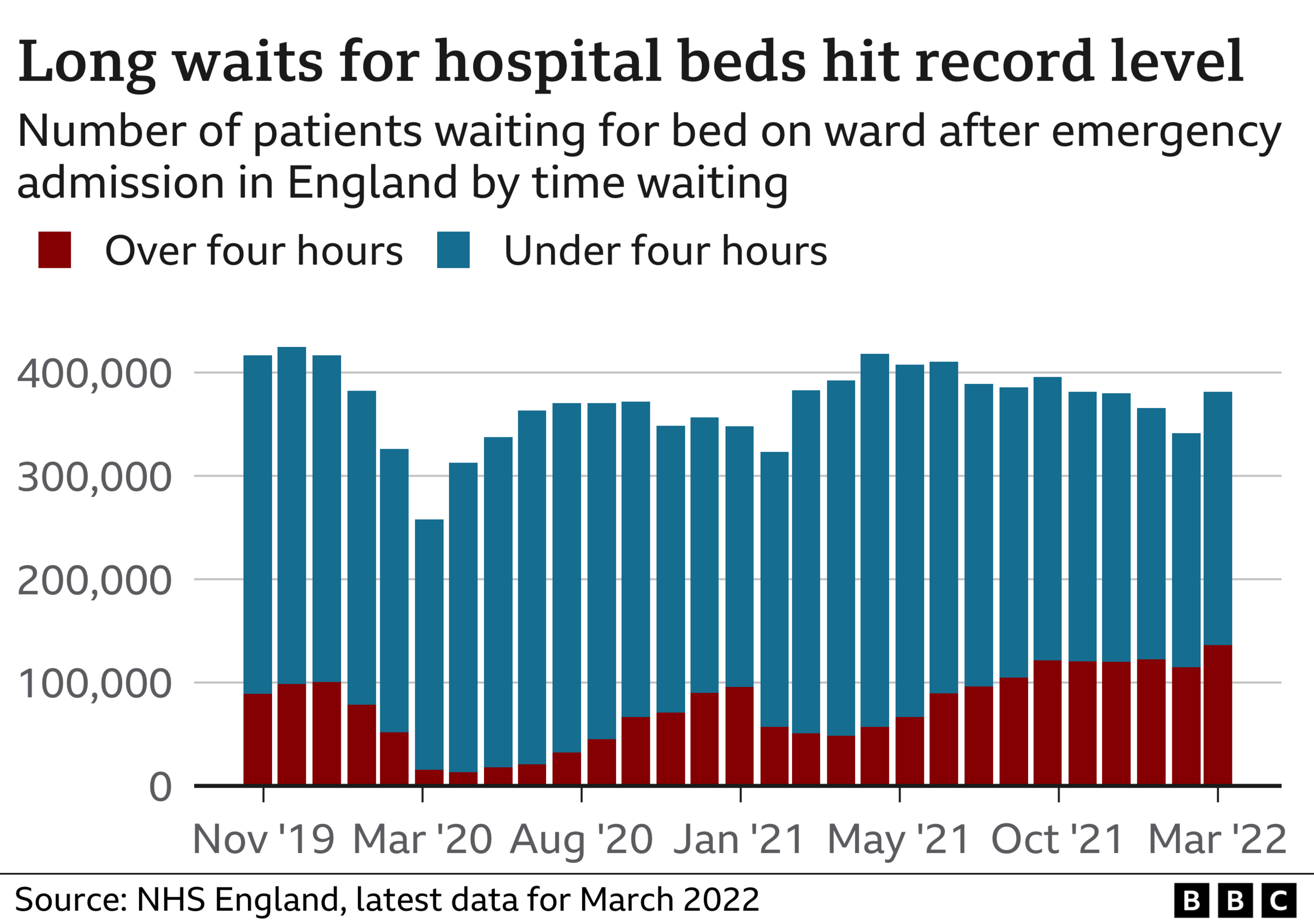

The pressure the system is under can be seen most acutely when the sickest patients in the emergency department need to be moved to a ward.

A record 22,506 people had to wait more than 12 hours on trolleys and in cubicles in A&E departments in March before they could be admitted to the main hospital. The figure is up from 16,404 in February, and is the highest for any month going back to August 2010 when the data started.

There are a number of factors playing a role in this - staff shortages, a lack of care in the community - which means some patients wait a long time to be discharged - and the fact that running hospitals has become more difficult because of Covid infection-control measures.

This past winter, 131,000 people have tested positive for the virus after being admitted to hospital in England. Around half of those will have been treated predominantly for Covid pneumonia and other direct symptoms of the disease; the others were brought in with other ailments.

Either way, that puts pressure on NHS services, as patients need to be isolated, entire hospital bays need to be cleaned and staff who fall sick have to take time off work.

Earlier this week, Matthew Taylor, from the NHS Confederation, which speaks for healthcare providers in England, told BBC Breakfast: "The brutal reality for staff and patients is that this Easter in the NHS is as bad as any winter."

All this means hospital waiting times have deteriorated across the board - not just in A&E but in ambulance response times, in cancer care and for planned surgery.

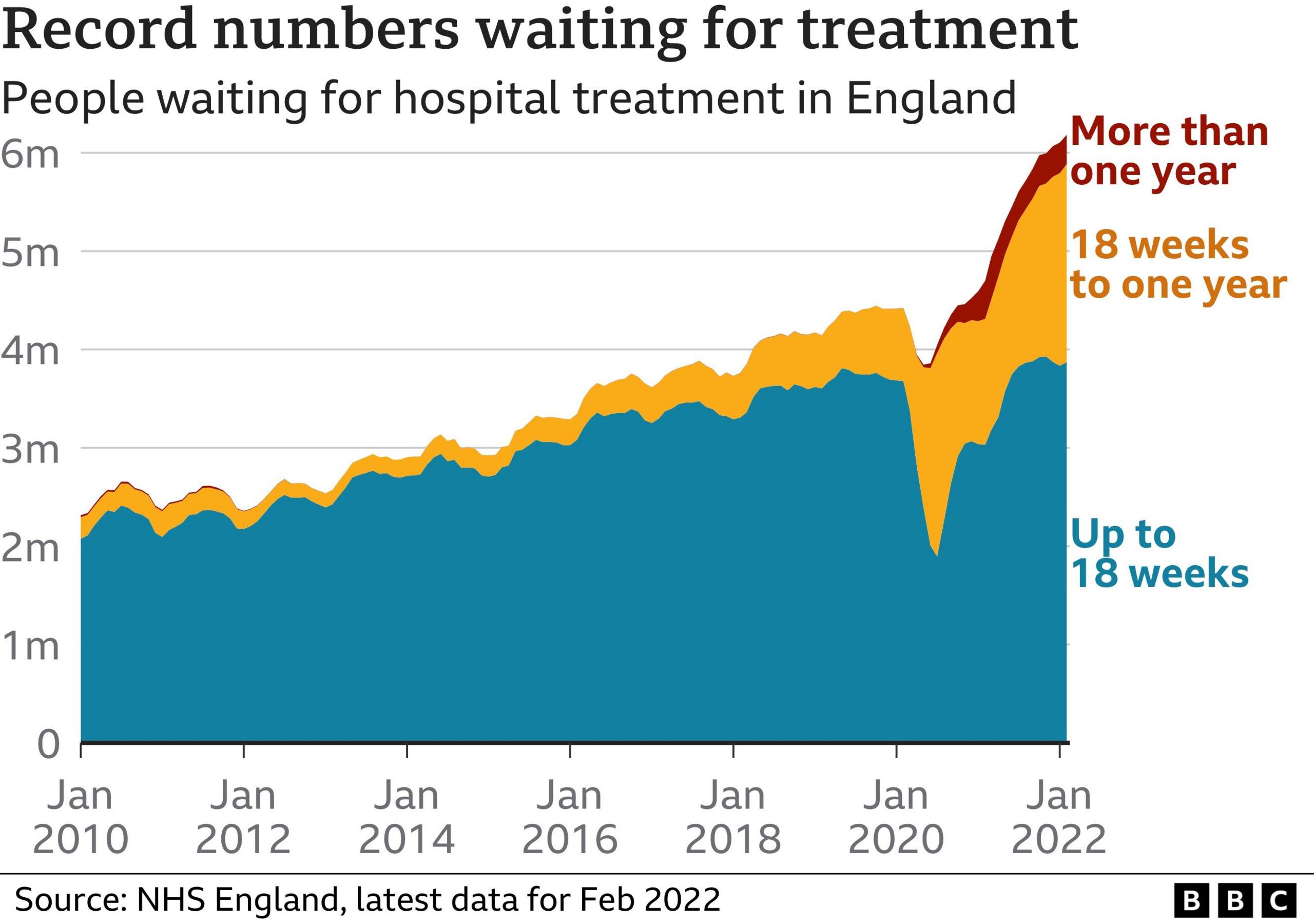

More than 6.2 million people in England are on a waiting list for routine treatment - that's one in nine of the population. More than 23,000 of them have waited more than two years for the likes of a hip replacement or gynaecology services - a nine-fold rise on last year, though down slightly on the previous month.

"Trusts are doing all they can to bear down on care backlogs, which have increased during the pandemic for hospital, mental-health and community services," says Chris Hopson, the chief executive of NHS Providers, which represents NHS Trusts. "But they face extraordinary pressures, including the continuing impact of Covid.

"What is needed is realism on what the NHS can achieve and how quickly, given the immediate pressure it is under."

Ambulances parked outside hospitals have become an increasingly familiar sight

To try to manage that pressure, NHS bosses have been overhauling some services and speeding up some treatments.

In Buckinghamshire, a new mobile cataract unit, designed to perform an extra 100 surgeries every week, has been set up in the grounds of Stoke Mandeville Hospital.

On Merseyside, a grandmother recently became the first person in the region to receive hip-replacement surgery and go home the same day.

New community diagnostic hubs have also started operating in places such as supermarket car parks to offer routine scans and blood tests. The NHS says 230,000 patients have been processed through those since the start of February.

Earlier this year the health service published its "elective recovery plan", pledging that every patient waiting more than two years for routine surgery should be treated by July.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesman said: "We know the NHS has been under unprecedented pressure - that's why we set out our plan to tackle the Covid backlog and deliver long-term recovery and reform, backed by our record multi-billion-pound investment.

"This will deliver new surgical hubs and up to 160 community diagnostic centres across the country to help patients get the surgery they need and earlier access to tests."

Related topics

- Published13 January 2022