Child hepatitis cases falsely linked to Covid vaccine

- Published

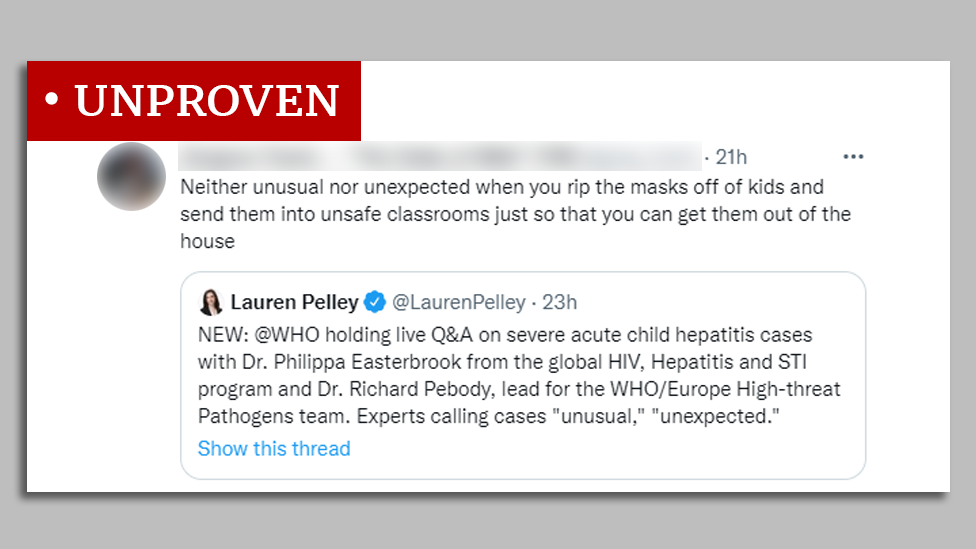

Social media posts have falsely linked a recent spike in unexplained hepatitis in children to the Covid vaccine.

The affected children were mostly under the age of five and therefore not eligible for the jab, health agencies monitoring the situation say.

But this hasn't stopped the claims - and other theories around lockdown or sending children back to school - being promoted as fact.

So what are the established facts of the cases so far?

As of 21 April 2022, the World Health Organization had recorded at least 169 cases of unexplained hepatitis - inflammation of the liver - in children in 11 countries since January. Of these, 114 were in the UK.

None of the five specific viruses (labelled A - E) which usually cause hepatitis was found, but the majority of youngsters tested did show up positive for a particular adenovirus - a common family of infections responsible for illnesses from colds to eye infections.

The specific one they had causes stomach bugs.

Dr Meera Chand, director of clinical and emerging infections at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), said their investigations "increasingly" suggested the rise was linked to adenovirus infection.

"However, we are thoroughly investigating other potential causes," she said.

Vaccine 'definitively' ruled out

The UKHSA says the Covid vaccine is the one thing they can definitively rule out - because none of the children affected had received the jab.

Nevertheless, on Twitter, Reddit, Facebook and Telegram, the BBC has found false claims that these hepatitis cases were caused by the Covid vaccine.

One post on Reddit highlighted the fact that an adenovirus is used in the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson Covid vaccines.

The adenoviruses used in the vaccines are harmless transporters which have been modified so they cannot replicate or cause infection.

Not only are they completely different adenoviruses to the ones found in the affected children, but these vaccines are largely being restricted to use in people aged 40 and over in the UK.

The average age of the children developing hepatitis is three - an age group not eligible for any of the Covid vaccines in the UK, where most of the cases have been recorded.

An article from a website known to contain false and misleading information about Covid, claiming the Pfizer vaccine was to blame, was shared on Facebook in English, Spanish, Italian, Chinese and Norwegian.

It quoted a much-misinterpreted study which has also been used to make misleading claims about the vaccines and fertility.

Is Covid to blame?

Some have claimed high levels of Covid and sending children back to school unmasked is to blame.

Unlike the vaccine theory, which is firmly discredited, the idea that a Covid infection could play a role in these cases is still being investigated as a possibility.

Small studies have found unusual cases of hepatitis in a handful of young children who had previously tested positive for Covid in Israel, external, Brazil, external, India, external and the US., external

This does not yet conclusively prove Covid played a role though.

Prof Anil Dhawan, a liver specialist at King's College Hospital London, who is treating some of these children, says at the moment he does not think Covid is driving these cases.

"Because if you look at number of patients, only 16% tested positive for Covid, and this [hepatitis] is not the feature of Covid," he said.

Hepatitis is a very rare known reaction to adenoviruses, he added.

Is it lockdown?

One line of inquiry is that children who haven't been exposed to as many infections in the early years of life because of the pandemic could be having outsized reactions to the adenovirus.

This has been seized on by some as proof lockdown was to blame for the outbreak.

But this is still a big unknown.

Dr Conor Meehan, a senior lecture in microbiology at Nottingham Trent University, agrees it is possible that not being exposed to as many bugs in their first months and years could have left these children's immune systems more vulnerable.

"The exposure that you have to viruses is important for building your immune system, and it mostly happens in the first five years of life," Dr Meehan explains.

"Most of these cases we see in under five-year-old kids, so they definitely haven't had the exposure that other kids would have had that are older," he says.

This makes its possible they could have a stronger reaction to an adenovirus infection.

But, "we would expect that stronger reaction to still just be worse versions of what we would normally see", in other words severe vomiting and diarrhoea, but not hepatitis.

This extremely unusual reaction suggests there is something else going on, Dr Meehan thinks, like a mutated virus or an interaction between two viruses.

However, more investigations are needed before we can say for sure what's causing these still very rare cases.

Looking for answers

Events that are both distressing and unexplained make fertile ground for confirmation bias - when people look for information to support what they already believe - according to Prof Gina Neff, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute.

There is a lot of uncertainty in this situation and understandably people are looking for answers, she says.

"When we search online, we feel like we're looking at a library and all the world's information is available to us," she explains.

But, argues Prof Neff, the results of our online searches are affected by what we've searched for before and by the algorithms used by search and social media companies.

- Published4 May 2022