Anti-abortion groups target women with misleading ads

- Published

Hana was worried for her own health when she sought abortion care - and was left feeling tricked

When Hana found out she was pregnant, she knew she wanted to have an abortion - but her search for a clinic on Google led her to an anti-abortion centre, set on talking her out of her decision.

In many US states, BBC News has seen misleading websites advertising these clinics appearing high up in Google search results - and Facebook adverts with inaccurate medical advice - while genuine abortion providers are having their ads rejected and accounts restricted.

Advice centres, such as the one visited by Hana - a 19-year-old living in the north-eastern US state of Massachusetts - are often run by Christian organisations.

They may offer some medical services such as pregnancy tests and ultrasounds - but some of their online promotion falsely suggests they also provide pregnancy-termination services.

It wasn't until Hana was walking down the centre's corridor, lined with posters comparing the procedure to murder, that it began to dawn on her this was not the abortion clinic she believed it to be.

'Get care'

Hana describes herself as a "nerdy researcher", studying a health-related course at college - but nothing about the clinic's website tipped her off to the service it actually provides.

The home page says: "Take control - start with a free abortion consultation." And in a tab labelled: "Get care," it lists the types of abortion (medical and surgical) that can be performed during different trimesters of pregnancy, under the heading: "You just found out you're pregnant and want to know your options."

Once there, Hana says, she was told, inaccurately, abortions were linked to infertility and breast cancer - and having had a Covid-19 vaccine, she might lose the pregnancy anyway, making abortion unnecessary, despite the evidence suggesting vaccinated people are no more likely to miscarry and, in fact, better protected against the risks of pre-term and still birth associated with Covid.

She was also pressured to view the ultrasound scan against her wishes.

"What kind of mother doesn't want to see a picture of their child?" asked the person attending to her.

Hana was left feeling deceived and betrayed.

'Choose life'

The Human Coalition, an anti-abortion group providing marketing for the centre and more than 40 others, told BBC News: "We find in our work, most abortion-determined women do not desire an abortion, they desire help.

"We're here to empower women by filling that gap - connecting women to the care and support they want, to choose life."

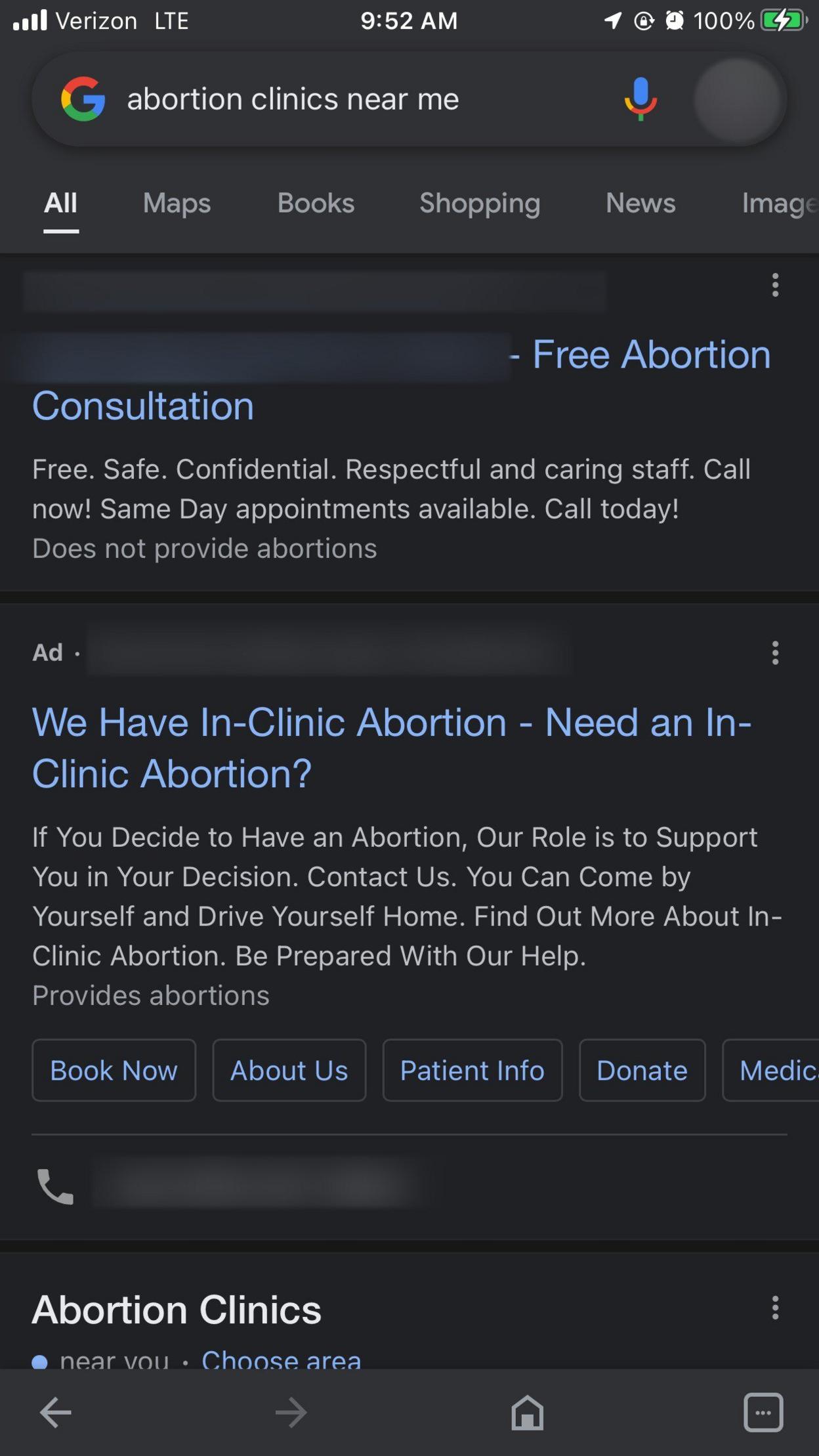

Google displays adverts above search results for certain terms.

Advertisers bid to have their ads appear first, Google says, although the order should also be determined by "relevance" and "overall quality".

But, Whitney Chinogwenya, of MSI Reproductive Choices (formerly Marie Stopes international) says, this creates a "battle of budgets", with regulated abortion clinics competing with anti-abortion clinics or unregulated pill providers for ad space on specific search terms.

Several large global abortion providers have also told BBC News they regularly have their online material referring to abortion censored without explanation, including having YouTube channels suspended, social-media accounts restricted and Facebook and Google ads rejected.

In 2019, having been criticised for hosting misleading adverts, Google tried to crack down on abortion-advice clinics, which are most common in the US but can also be found across Europe (including the UK), Africa and Latin America.

In the US, UK and Ireland, anyone running an ad mentioning abortion must first apply for a certificate.

Ads from advice clinics not offering abortions can still run but will be given a disclaimer the advertiser "does not provide abortions".

Hana says she did not see this disclaimer.

It appears in very small font underneath the search headline and description.

Sarah Eagan, a researcher for campaign group the Center for Countering Digital Hate, questions whether Google should be taking money at all for anti-abortion ads that target keywords used by people actively seeking terminations.

The CCDH has also found anti-abortion ads promoting unproven medicines remaining on Facebook.

And at the other end of the spectrum, the researchers found Google's autocomplete function suggesting ineffective do-it-yourself abortion methods.

Kelly, like Hana, says she was given inaccurate medical information as she struggled to find an affordable and safe way to terminate her pregnancy in her home state of Texas.

Kelly said she clicked on the clinic's website in desperation, knowing she couldn't afford a doctor.

Between jobs and without insurance, she could not afford "an actual doctor's visit" so searched for affordable clinics.

Finding her way to an anti-abortion centre, Kelly says she was frightened with warnings she could "bleed out" and risk her life but not given the context medical abortion is an extremely safe procedure.

Kelly feels promoting free pregnancy tests targets low-income women.

The centre appears to be using organic search, not adverts, making it more complicated to regulate.

It says its website clearly states: "We do not refer or perform abortions," adding it provides "free services annually to over 5,000 minority poor under-served single mothers".

Two drugs are used for a medical abortion - misoprostol and mifepristone

Eventually, Kelly was prescribed termination drugs - just hours before she passed the 12-week limit for a safe medical abortion.

But Elisa Wells, co-founder of Plan C, the organisation that helped Kelly access these abortion pills, says its online material is routinely "disallowed for violating community standards" on Facebook, Instagram and Google.

Google says it has clear policies governing abortion-related ads, some determined by local laws and regulations.

Some of the posts and channels flagged by BBC News had been removed in error and since reinstated, it said.

Facebook said it had restored a small number of incorrectly rejected ads for abortion providers.