Monkeypox: Time to worry or one to ignore?

- Published

If you're still reeling from the Covid pandemic, well sorry but there's another virus to get to grips with. This time it's monkeypox and there are around 80 confirmed cases in 11 countries, including the UK, that would not normally expect to have the disease.

So what is going on? Is it time to worry or are we getting overly excited having just lived through Covid?

Let's be clear: this is not another Covid and we're not days away from lockdowns to contain the spread of monkeypox.

However, this is an unusual and unprecedented monkeypox outbreak. It has taken scientists who specialise in the disease by complete surprise and it is always a concern when a virus changes its behaviour.

Until now, monkeypox was pretty predictable.

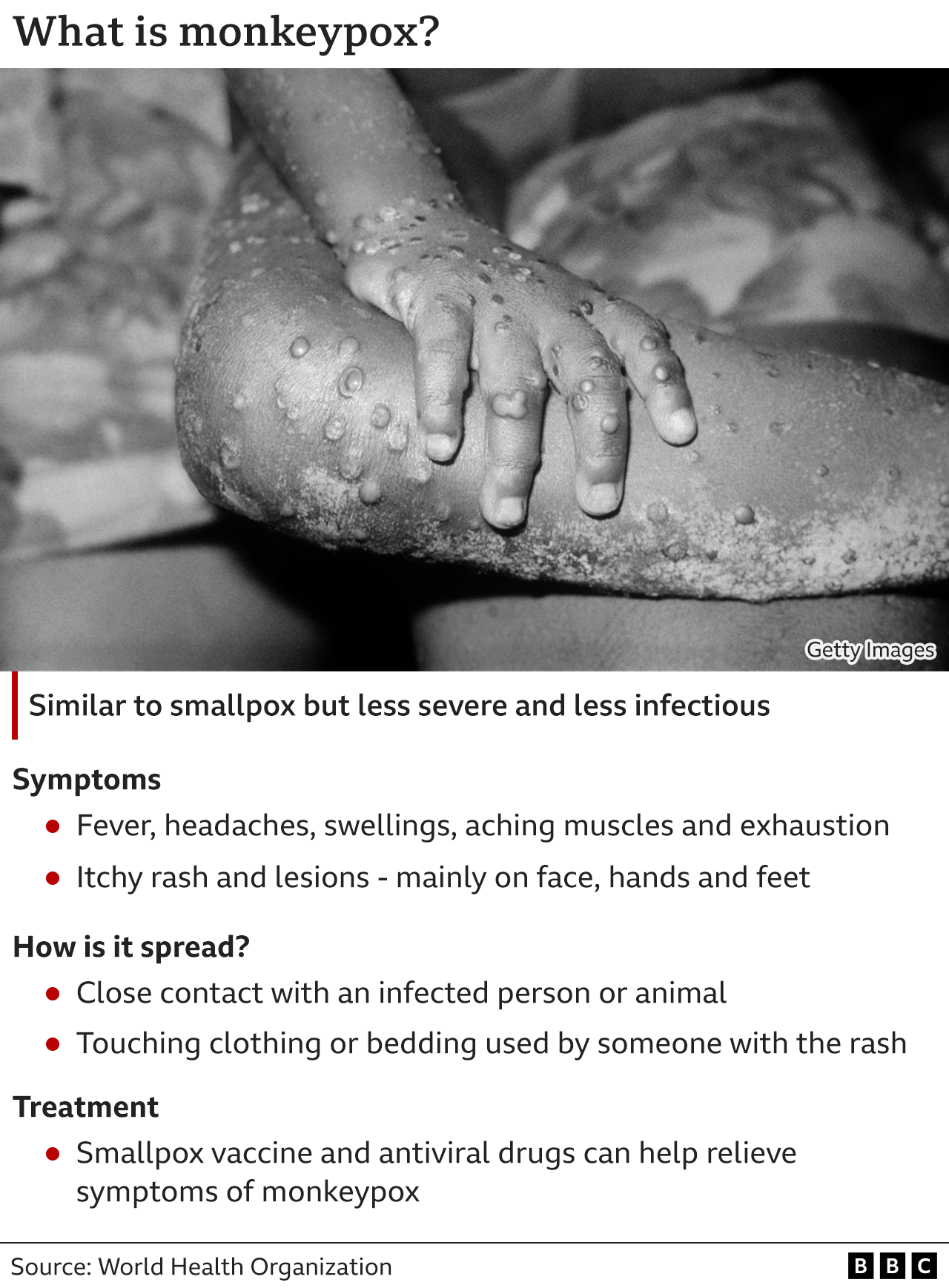

The virus's natural home is wild animals, which are actually thought to be rodents rather than monkeys. Somebody in the rainforests of Western and Central Africa comes into contact with an infected creature and the virus makes the jump across species. Their skin erupts in a rash, which blisters and then scabs over.

The virus is now outside its usual home and struggles to spread so it needs prolonged close contact to keep going. So outbreaks tend to be small and burn out on their own.

Small numbers of cases have cropped up elsewhere in the world before, including the UK, external, but all can be immediately linked to somebody travelling to an affected country and bringing it home.

That is no longer the case.

For the first time the virus is being found in people with no clear connection to Western and Central Africa

It is not clear who people are catching it from

Monkeypox is spreading during sexual activities with most cases having lesions on their genitals and the surrounding area

Many of those affected are gay and bisexual young men

"We're in a very new situation, that is a surprise and a worry," Prof Sir Peter Horby, the director of the University of Oxford's Pandemic Sciences Institute, told me.

While he says this is "not Covid-Two", he said "we need to act" to prevent the virus getting a foothold as this is "something we really want to avoid".

Dr Hugh Adler, who has treated patients with monkeypox, agrees: "It's not a pattern we've seen before - this is a surprise."

So what's going on?

We know this outbreak is different, but we don't know why.

There's two broad options - the virus has changed or the same old virus has found itself in the right place at the right time to thrive.

Monkeypox is a DNA virus so it does not mutate as rapidly as Covid or flu. Very early genetic analysis, external suggests the current cases are very closely related to forms of the virus seen in 2018 and 2019. It is too early to be sure, but for now there is no evidence this is a new mutant variant at play.

But a virus doesn't have to change in order to take advantage of an opportunity, as we have learned from unexpected large outbreaks of both Ebola and Zika virus in the last decade.

"We always thought Ebola was easy to contain, until that wasn't the case," said Prof Adam Kucharski, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

It's not clear why gay and bisexual men are disproportionately affected. Are sexual behaviours making it easier to spread? Is it just coincidence? Is it a community that is more aware of sexual health and getting checked out?

It may also be getting easier for monkeypox to spread. The mass smallpox vaccinations of the past would have given older generations some protection against the closely related monkeypox.

"It is probably transmitting more effectively than in the smallpox era, but we're not seeing anything suggesting it could run rampant," said Dr Adler, who still expects this outbreak to burn itself out.

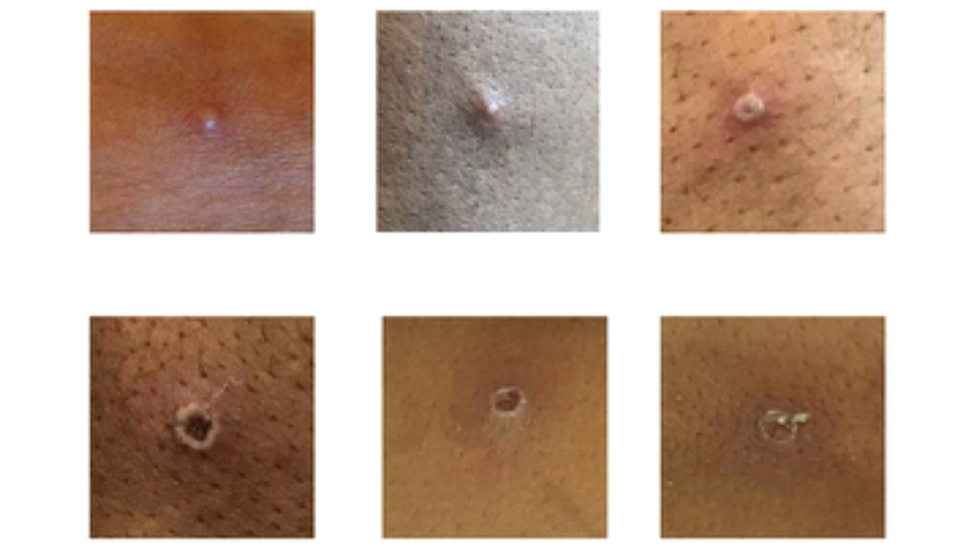

The rash changes and goes through different stages, and can look like chickenpox or syphilis, before finally forming a scab, which later falls off

Understanding how this outbreak started will help predict what happens next.

We know we're only seeing the tip of the iceberg as the cases being detected don't fit into a neat picture of this person passed it on to that person etc. Instead many of the cases appear unrelated, so there are missing links in a chain that seems to spread across Europe and beyond.

A recent massive superspreading event, in which large numbers of people gathered and caught monkeypox at the same venue such as a festival and then took it home to different countries, could explain the current situation.

The alternative explanation for so many unconnected people getting infected is if the virus has actually been bubbling along unnoticed for quite some time involving a lot of people.

Either way, we can expect to continue to find more cases.

"I don't think the general public need to be worried at this stage, but I don't think we've uncovered all of this and we are not in control of this," said Prof Jimmy Whitworth, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But remember we are not in the same situation as we were with Covid.

Monkeypox is a known virus rather than a new one, and we already have vaccines and treatments. It is mostly mild, although it can be more dangerous in young children, pregnant women and people with weak immune systems.

But it spreads more slowly than Covid and the distinctive and painful rash makes it harder to miss than a cough that could be anything. This makes the job of finding people who may have been infected and vaccinating those at risk of catching it easier.

However, the World Health Organization's regional director for Europe, Hans Kluge, has warned that "as we enter the summer season... with mass gatherings, festivals and parties, I am concerned that transmission could accelerate".

Follow James on Twitter , external