Polio: What is it and how does it spread?

- Published

The virus that causes polio has been found in a concerning number of sewage samples in London and all children aged one to nine years old are to be offered a polio booster jab.

There have been no confirmed cases of people becoming ill with the disease in the UK, but health officials want to ensure children in London are completely protected.

What is polio and how does it spread?

It can be a serious infection, caused by a virus which spreads easily through contact with the faeces (poo) of an infected person or less commonly through droplets when they cough or sneeze.

It mostly affects children under five years old.

The majority of people with the infection have no symptoms but some feel like they have the flu with:

a high temperature

sore throat

headache

stomach pain

aching muscles

feeling sick

A small number of infected people - between one in a thousand and one in a hundred - develop more serious problems where polio invades the nervous system. This causes paralysis, usually of the legs.

This is not normally permanent and movement often comes back gradually.

But it can be life-threatening - particularly if paralysis affects muscles used for breathing.

What age do you get the polio vaccine?

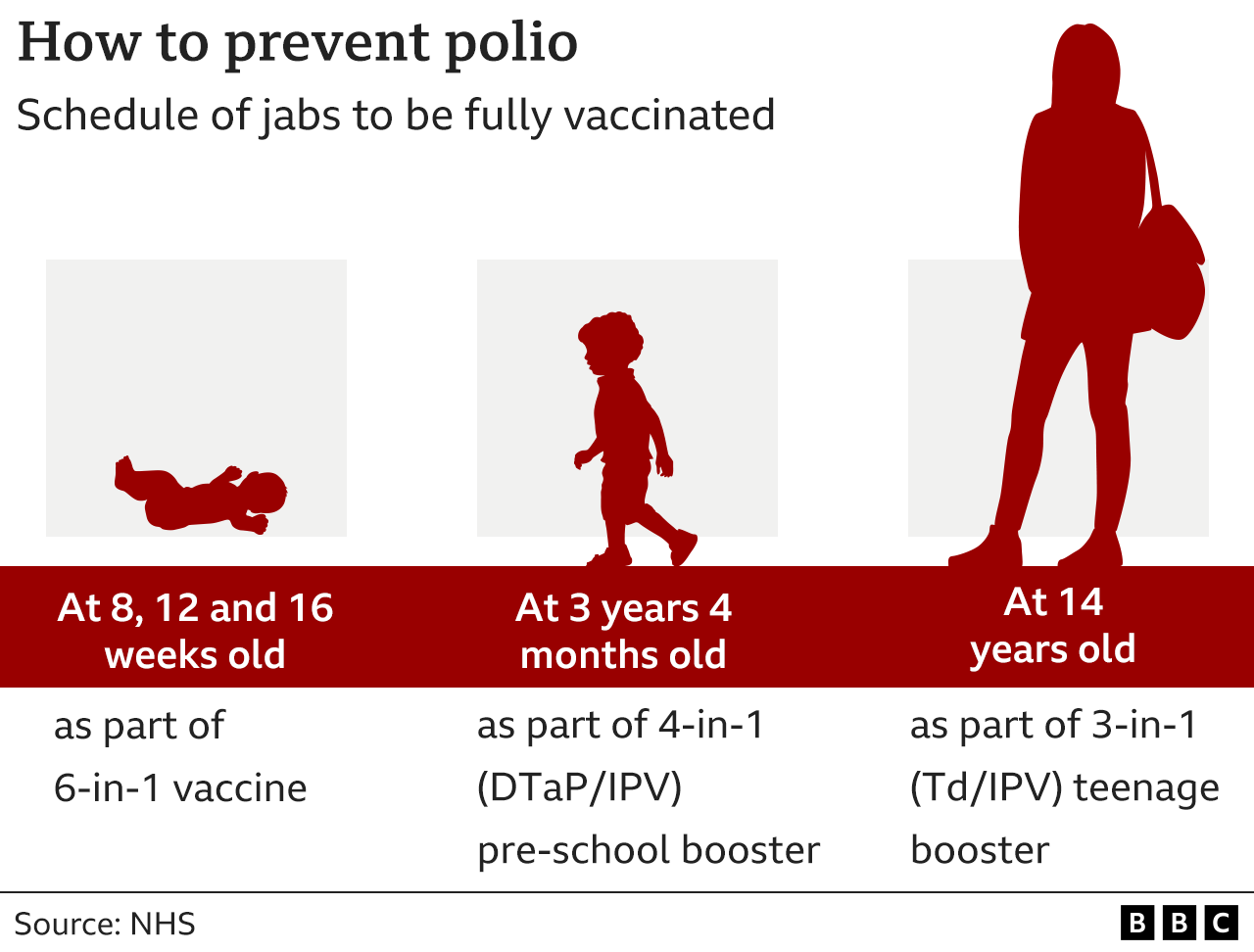

The UK used to use a highly effective oral polio vaccine that came as drops. It has switched to the newer, injectable form.

The NHS offers five doses from the ages of 8 weeks to 14 years as part of routine childhood jabs.

People need to have all five doses of the vaccination to be fully immunised against the disease.

How are children being protected?

Parents and carers of nearly one million children in Greater London will be contacted by their GP within the next month so they can get another polio vaccine, called a booster.

Experts say this will act as an extra precaution to stop polio spreading, even for children who are already up to date with their vaccines.

The NHS in London is contacting contact parents when it's their child's turn to come forward.

Parents are urged to take up the offer of the top-up dose - whether it's a booster or a catch-up one they had missed - as soon as possible.

This is to make sure they have a high level of protection from paralysis.

How many children have been vaccinated?

Take-up of the first three doses is about 86% in London, well below target levels, with the rest of the UK at over 92%.

This may in part be down to some populations in the capital moving regularly, making it harder to access vaccines at the right time.

Figures for 2020/21 suggest some 34,000 children aged five in London had not received their fourth dose out of five.

Is polio a problem worldwide?

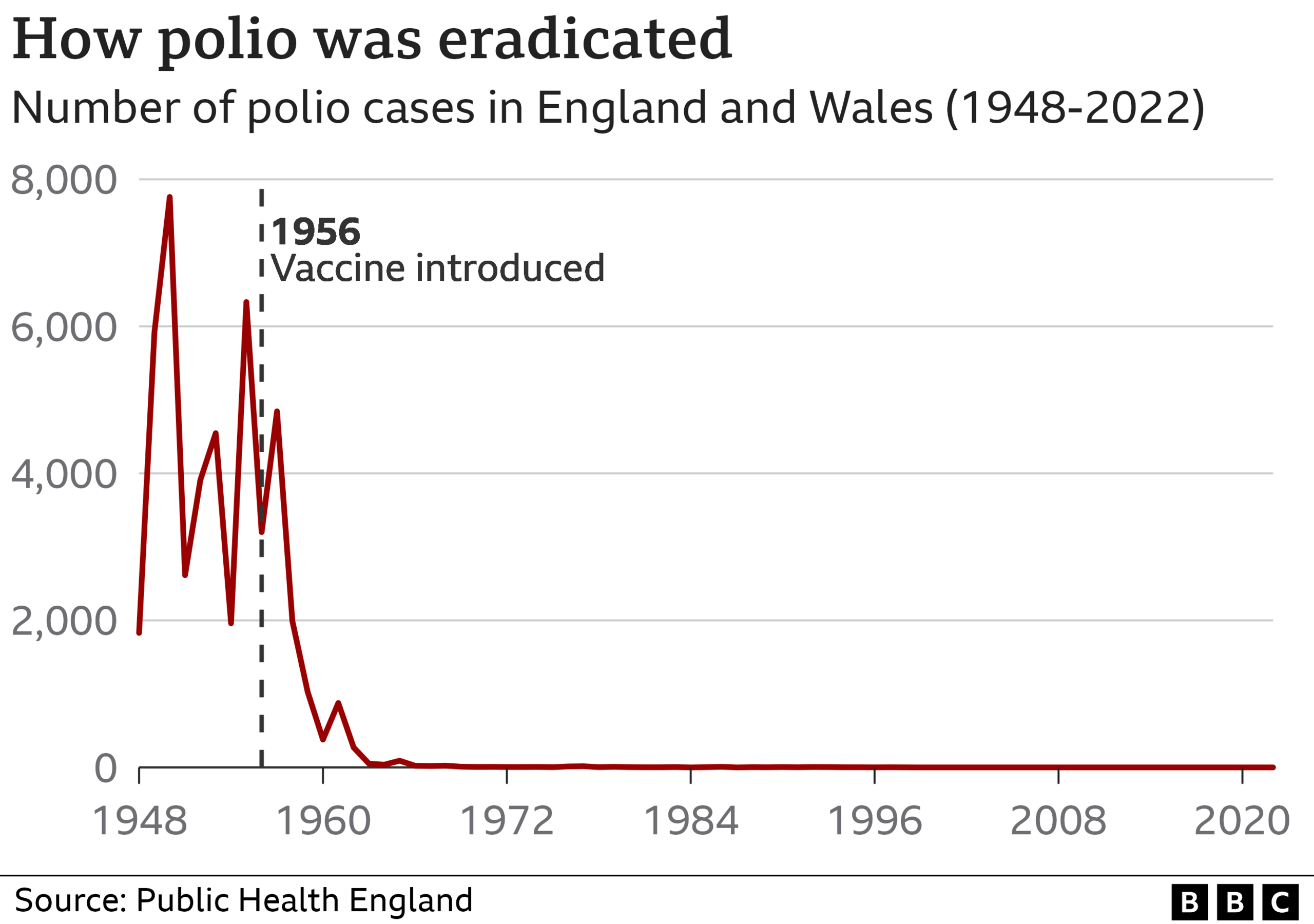

Cases have decreased by more than 99%, external since 1988, from an estimated 350,000 cases in more than 125 countries then to 175 reported globally in 2019.

All continents, except Asia, have been certified as polio free.

The last person recorded to have acquired the wild virus in the UK was in 1984.

There are a few countries where the disease is still found - it includes war-torn Afghanistan and Pakistan, where it has been difficult to vaccinate everyone.

Globally, 83% of infants had received three doses of polio vaccine in 2020, according to the World Health Organization.

Are there different kinds of polio?

Wild poliovirus is the most commonly known form.

But there is another type linked to the oral form of the vaccine.

The vaccine offers excellent protection against wild polio, is easy to use and has been deployed by many countries around the world - keeping millions of people safe.

However, it contains a weakened, live form of the virus which can replicate harmlessly in the gut. But that means some is then excreted in poo.

In rare cases, this weakened form can spread to unvaccinated people.

Over a long period the vaccine-derived virus might change to become more like wild polio.

Many industrialised countries now use the newer injectable form which contains a killed version of the virus.

Both vaccines are safe and effective.

In the last decade - a period during which more than 10 billion doses of oral polio vaccine were given worldwide - vaccine-derived-polio virus outbreaks resulted in fewer than 800 cases.

In the same period, in the absence of vaccination with the oral polio vaccine, more than 6.5 million children would have been paralysed by wild poliovirus.

Why is the polio virus back?

A tiny number of samples of the polio virus are detected each year in the UK during sewage surveillance. However, this is the first time that a genetically-linked cluster has been found repeatedly over a period of months.

The polio virus detected in London most likely came from someone who had recently received an oral polio vaccine.

They will then have shed the weakened vaccine virus in their stools.

It is likely it was then passed on to another person at this point and has since infected some others. None have sought medical help though.

Similar traces of the virus, which could be linked, have also been found in sewage in Jerusalem, in Israel, and in New York state in the United States.

How much of a problem is it?

The UK is so far taking the right approach, according to Sir Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust.

"It's a credit to the surveillance systems, it's a credit UK Health Security Agency for picking this up and then taking the right public health approaches."

And Prof Paul Hunter, professor of medicine at UEA, said getting more people vaccinated would help stop the virus.

Graphics by Visual Journalism Team

Related topics

- Published10 August 2022

- Published22 June 2022

- Published25 September 2015

- Published25 August 2020