Did we all believe a myth about depression?

- Published

A study showing depression isn't caused by low levels of the "happy hormone" serotonin has become one of the most widely shared medical articles.

It has provoked a wave of misleading claims about antidepressant drugs, many of which increase the amount of serotonin in the brain.

This research, external doesn't show the drugs aren't effective.

But the response to it has also sparked some genuine questions about how people treat, and think about, mental illness.

After Sarah had her first major psychiatric episode, in her early 20s, doctors told her the medication she was prescribed was like "insulin for a diabetic". It was essential, would correct something chemically wrong in her brain, and would need to be taken for life.

Her mother had type 1 diabetes, so she took this very seriously.

Sarah stayed on the drugs even though they seemed to make her feel worse, eventually hearing menacing voices telling her to kill herself and being given electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Yet the claim she needed the drug like a diabetic needs insulin wasn't based on any medical evidence.

"You feel betrayed by the people that you trusted," she says.

Her reaction to the drugs was extreme but the "chemical imbalance" message she was given was not unusual.

Sarah and her mother, who took insulin for type 1 diabetes

Many psychiatrists say they have long known low levels of serotonin are not the main cause of depression and this paper doesn't say anything new.

Yet the unusually large public response to it suggests this was news to many.

But some made an inaccurate leap from saying antidepressants don't work by fixing a chemical imbalance, to saying they don't work at all.

And doctors fear, in the confusion, people might stop taking their medication abruptly and risk serious withdrawal effects.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, external (NICE) says these drugs shouldn't be stopped abruptly except in medical emergencies and reducing the dose slowly can minimise withdrawal symptoms.

Sarah has since developed speech and movement difficulties

What did the research show?

This latest research looked at 17 studies and found people with depression didn't appear to have different levels of serotonin in their brains to those without.

The findings help to rule out one possible way the drugs might work - by correcting a deficiency.

"Many of us know that taking paracetamol can be helpful for headaches and I don't think anyone believes that headaches are caused by not enough paracetamol in the brain," Dr Michael Bloomfield points out.

So do antidepressants work?

Research suggests antidepressants on average do work marginally better than placebos (dummy drugs people are told could be the real thing). There are debates among researchers about how significant this difference is.

Within that average is a group of people who experience much better results on antidepressants - doctors just don't have a good way of knowing who those people are when prescribing. And there is a group who will fare much worse.

Some people who take anti-depressants say the drugs have helped them during a mental health crisis, or allow them to manage depression symptoms day to day.

Prof Linda Gask, at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, says antidepressants are "something that help a lot of people feel better quickly", especially in a crisis.

But one of the authors of the serotonin paper, Prof Joanna Moncrieff, points out most research by drug companies is short-term, so little is known about how well people do after the first few months.

"You have to say we will continue to review them and we won't keep you on them any longer than you need to be on them," something which often doesn't happen, Prof Gask agrees.

While there are risks to leaving depression untreated, some people will experience serious side-effects from antidepressants - which the serotonin study's authors say need to be more clearly communicated.

These can include suicidal thoughts and attempts, sexual dysfunction, emotional numbing and insomnia, according to NICE.

Since last autumn, UK doctors have been told they should offer therapy, exercise, mindfulness or meditation to people with less severe cases of depression first, before trying medication.

Local health teams might offer group therapy, recommend exercise or community activities

How was the research talked about?

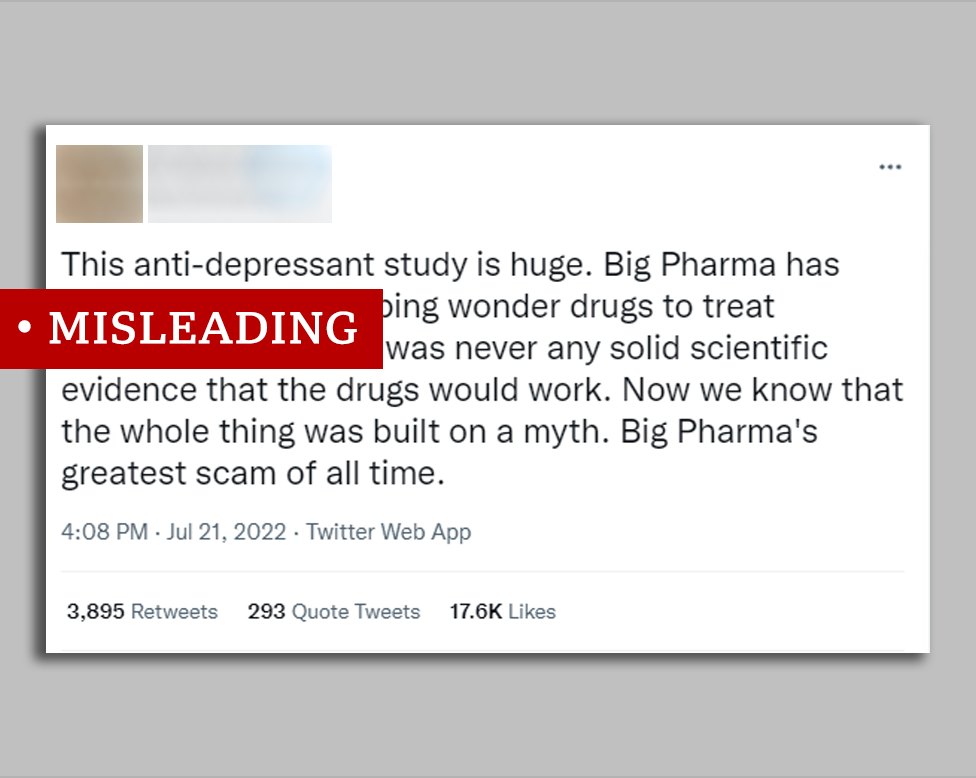

One typical misleading response claimed the study showed the prescribing of antidepressants was "built on a myth".

But the study didn't look at antidepressant use at all.

Serotonin plays a role in mood, so tweaking it can make people feel happier at least in the short term, even if they didn't have abnormally low levels to start with. It may also help the brain make new connections.

Others have claimed this study shows depression was never an illness in people's brains but a reaction to their environments.

"Of course it's both," Dr Mark Horowitz, one of the paper's author, says.

"Your genetics affects your sensitivity to stress," for example.

But people having an understandable response to difficult circumstances might be better helped with "relationship counselling, financial advice, or a change of jobs" than medication.

However, Zoe, who lives in south-east Australia and experiences both severe depression and psychosis, says rebranding depression as "distress" that would go away if we "just fix all the social problems" is also too simplistic and overlooks people with more severe mental illnesses.

Psychosis runs in her family, but episodes are often triggered by stressful events such as exam deadlines.

Zoe says she has found medication, including antidepressants, life-changing and has been able to make a "calculation" side-effects are "worth it" to avoid severe episodes.

And that's one things all of the experts who spoke to BBC News agree on - patients need to have more information, better explained so they can make these difficult calculations for themselves.

For details of organisations offering advice and support, go to BBC Action Line.

Some contributors asked that their surnames be withheld

Follow Rachel on Twitter, external or email your stories about antidepressants to rachel.schraer@bbc.co.uk.