ONS: Why is the number of deaths higher than expected?

- Published

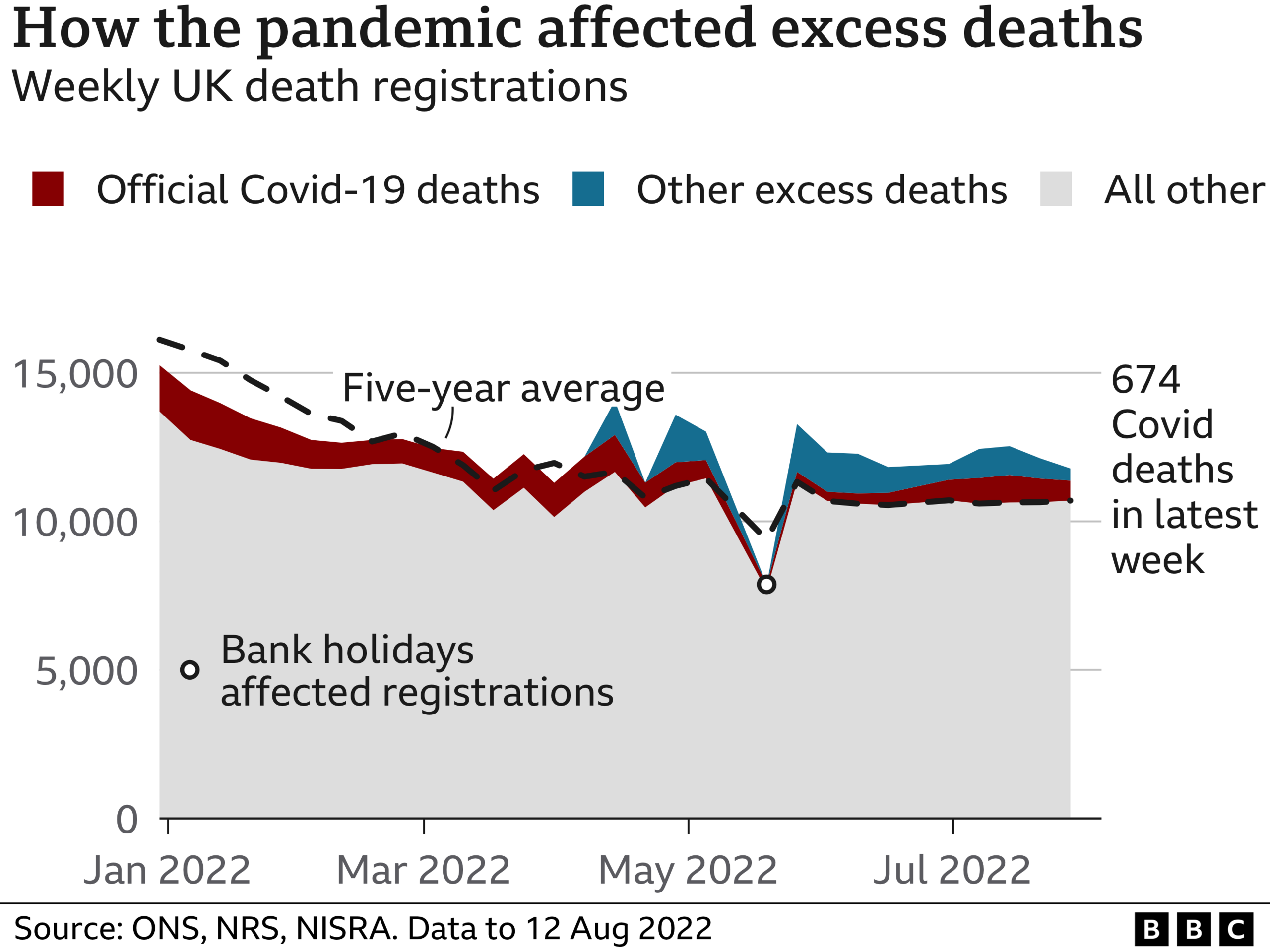

The threat from Covid may have receded, but renewed concerns are being raised about the high number of total deaths being recorded.

Data from the national statisticians for the UK suggests during the past 10 weeks the number has been 12% higher than would have been expected, based on the average for previous years.

Covid-related deaths are - as they have been for much of the past year - pretty low, accounting for about 4% of deaths in July, making it the sixth-biggest cause of death. So what else could be causing this spike?

The hot weather the country has experienced in recent weeks is a factor - albeit a small one.

Data from the Office for National Statistics, external shows on the days with extreme heat - around half of the days during July - deaths rates were more than 6% higher in England than they were on other days.

Many factors could be at play

Another issue is the ageing population. The headline excess deaths data does not take into account the fact that there are now more older people. This may be responsible for more than half of the excess.

What about the rest? One theory is that people have been left more frail because of a previous Covid infection - research suggests an infection can lead to a higher risk of heart problems subsequently.

The pandemic has also led to people becoming unhealthier, with alcohol consumption and physical-inactivity levels increasing.

And in the early stages of the pandemic, many people stayed away from the NHS - visits to A&E dropped by more than 50%. Some have suggested the public health messaging and fear it caused went too far.

The drop-off in people using the NHS has raised fears of an increase in late diagnoses for cancer and a worsening of chronic illnesses, such as heart disease.

There are no signs of cancer deaths increasing yet - these could take some years to filter through. But Macmillan Cancer Support estimates there are still more than 30,000 missing cancer cases - people who have not yet been diagnosed and whose survival chances will be put at risk by later-stage diagnoses.

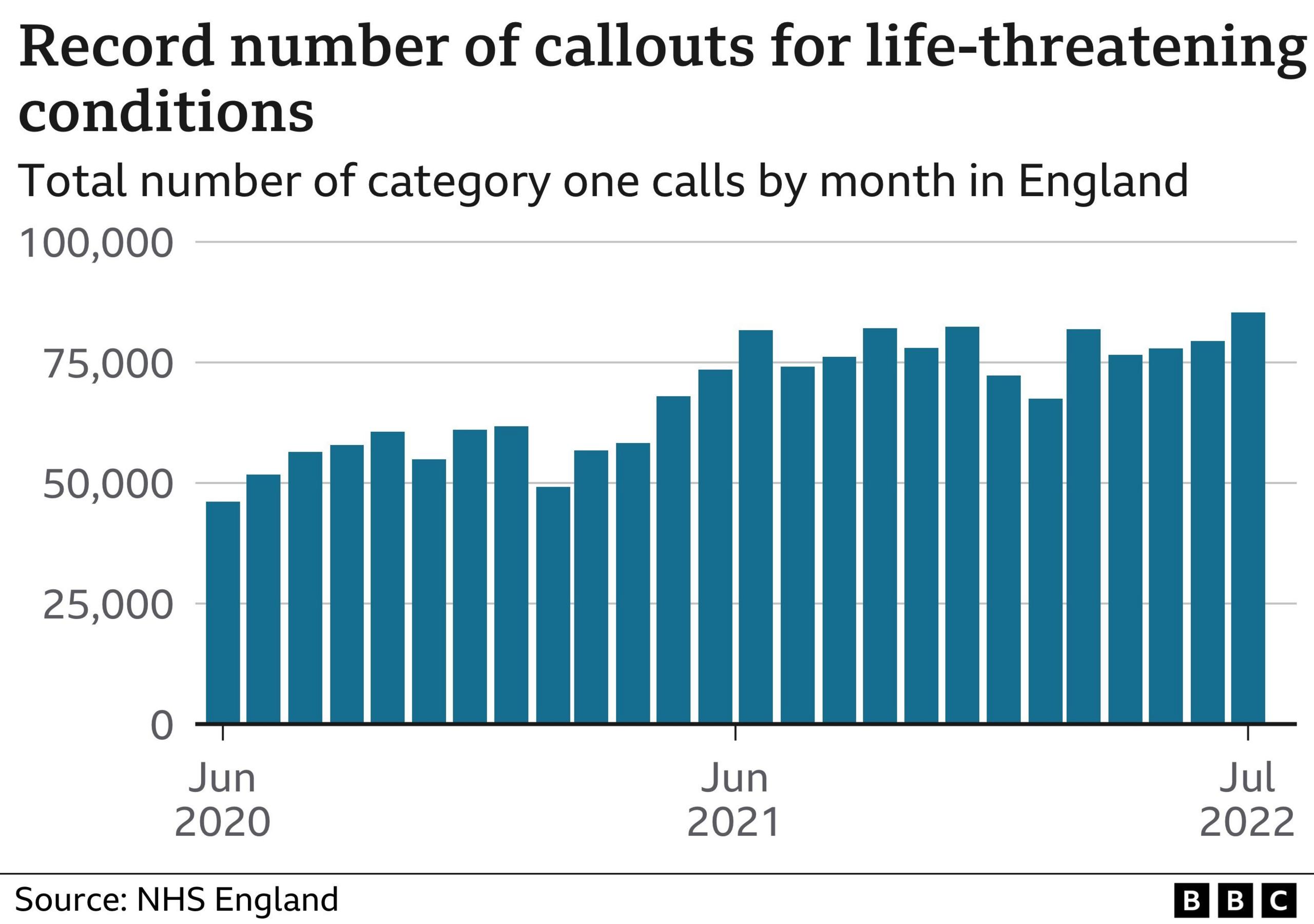

And, of course, there is a strong suspicion that the way the emergency care system is struggling at the moment is playing a key role, too.

Performance was deteriorating before the pandemic, following a decade of squeezed funding, but the pandemic has exacerbated the situation with demand and waits both rising.

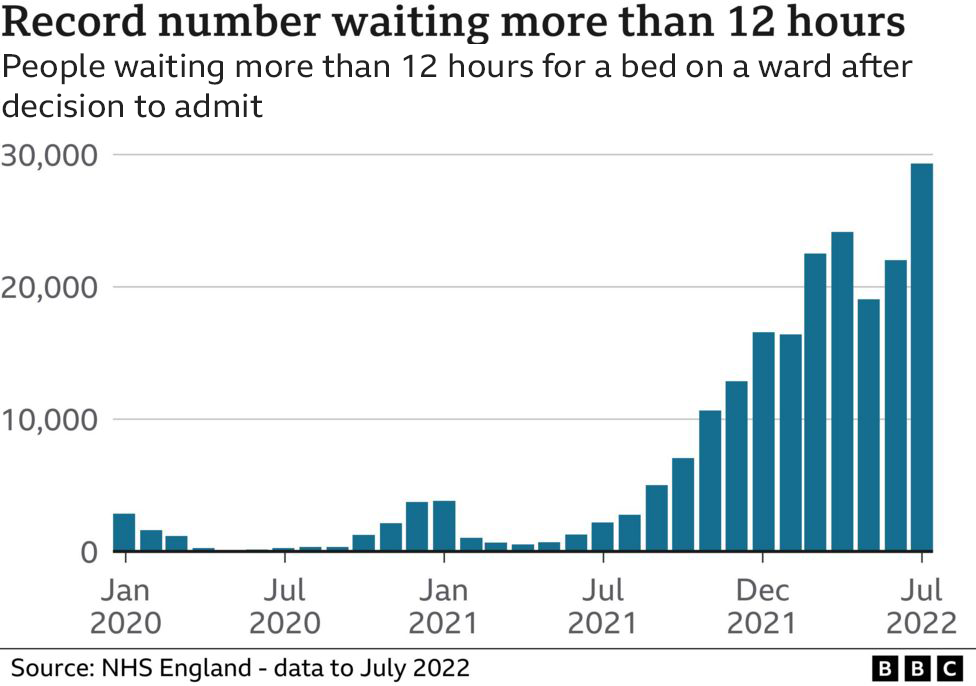

Perhaps most worryingly, it is taking ambulance crews much longer than they should to get to 999 calls, and when patients do reach hospital they face further delays - 12-hour waits are at record levels in England.

And these are just the tip of the iceberg - because of the way waiting times are collected these waits include only the time taken after the decision to admit a patient. They may well have spent hours already waiting to be seen in A&E.

Such delays, of course, put people at risk.

Earlier this month, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine warned the system was experiencing a "sharp demise" in performance and that patients were being harmed.

It said it dreaded to imagine what would happen this winter, when pressures typically get worse, and urged ministers to take more action.

Whatever the cause, though, one thing is certain - the pandemic's impact on health is going to last quite some time yet.

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022