Synthetic mouse embryo develops beating heart

- Published

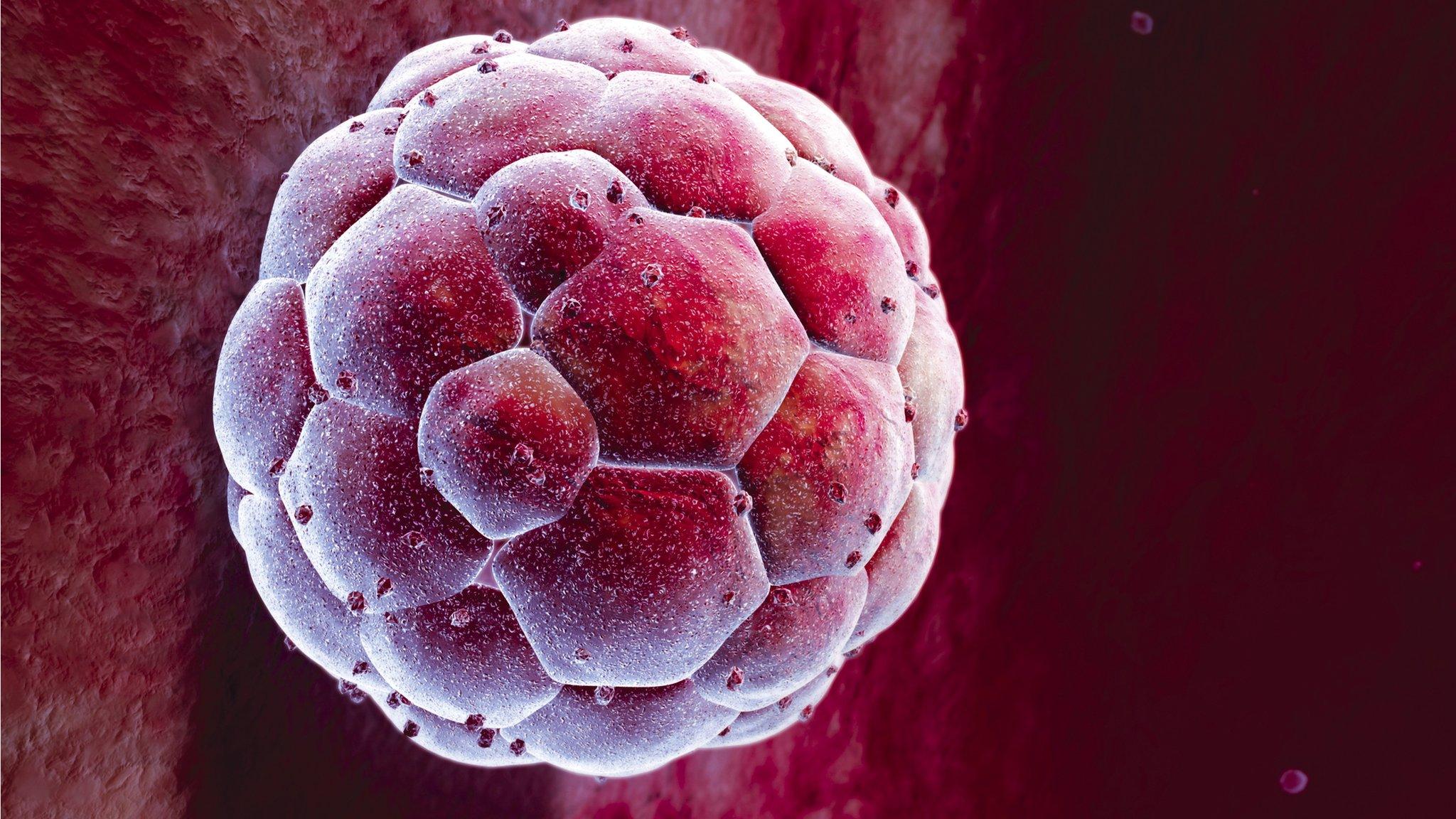

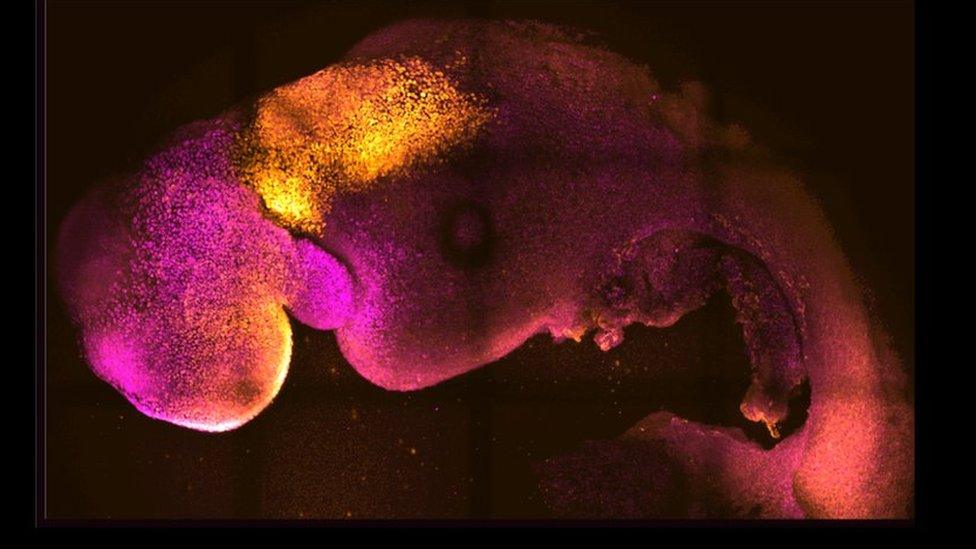

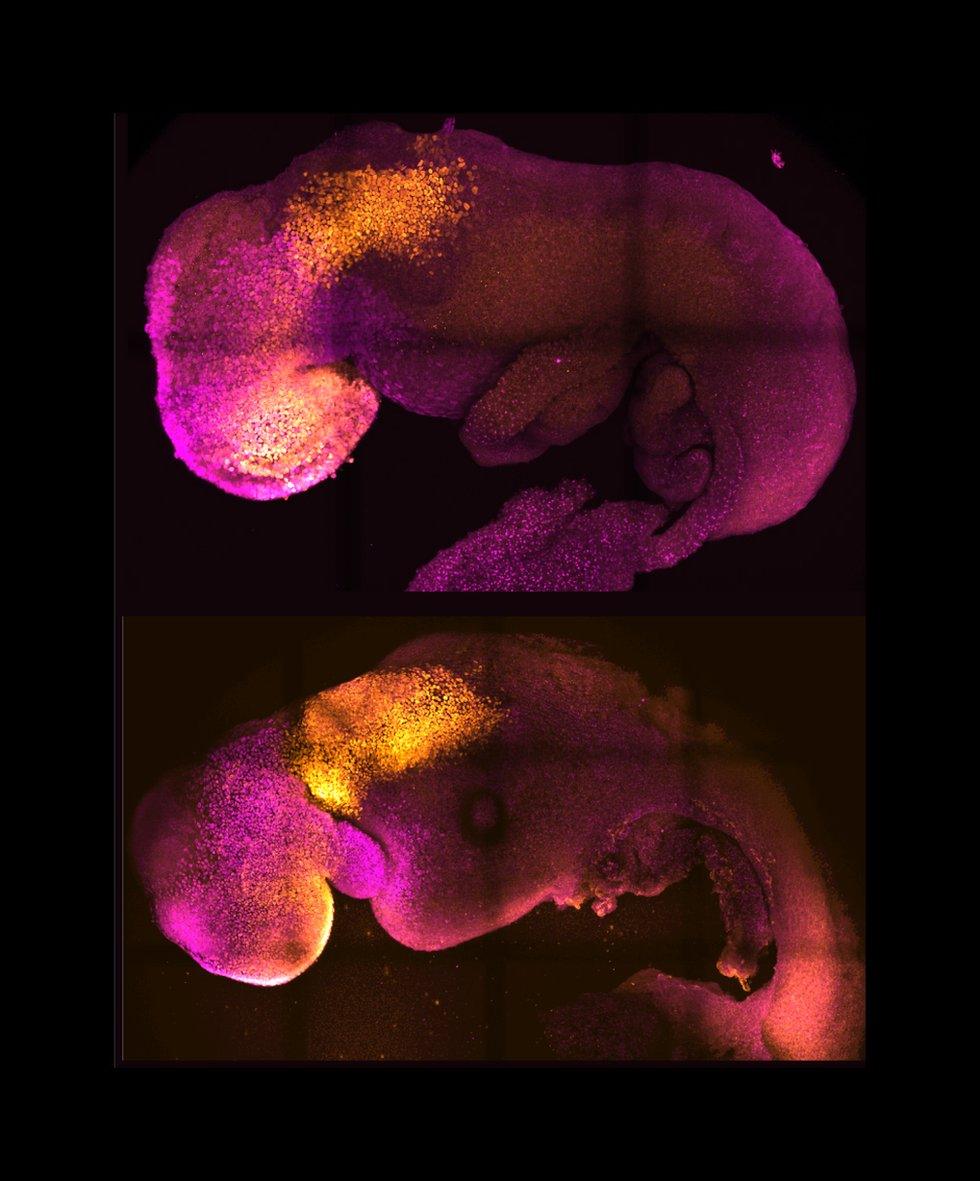

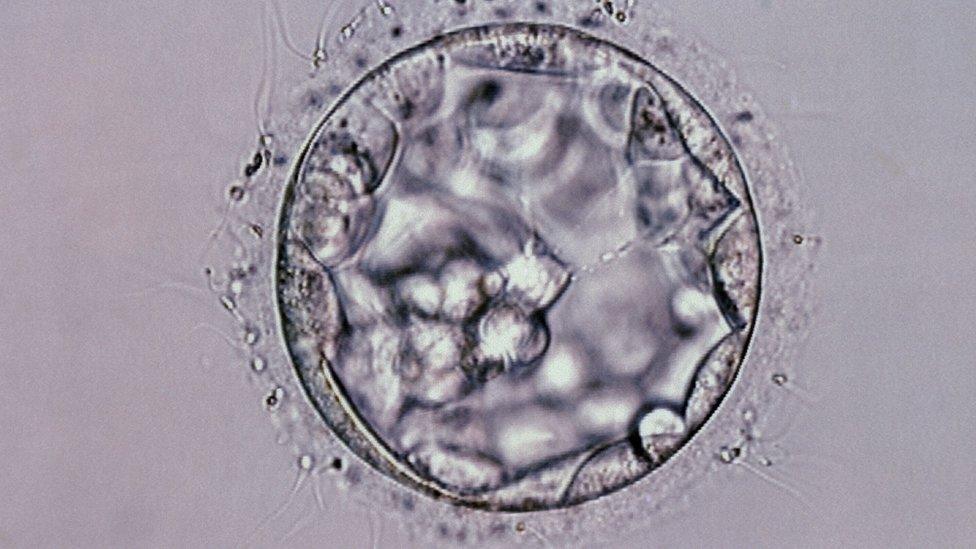

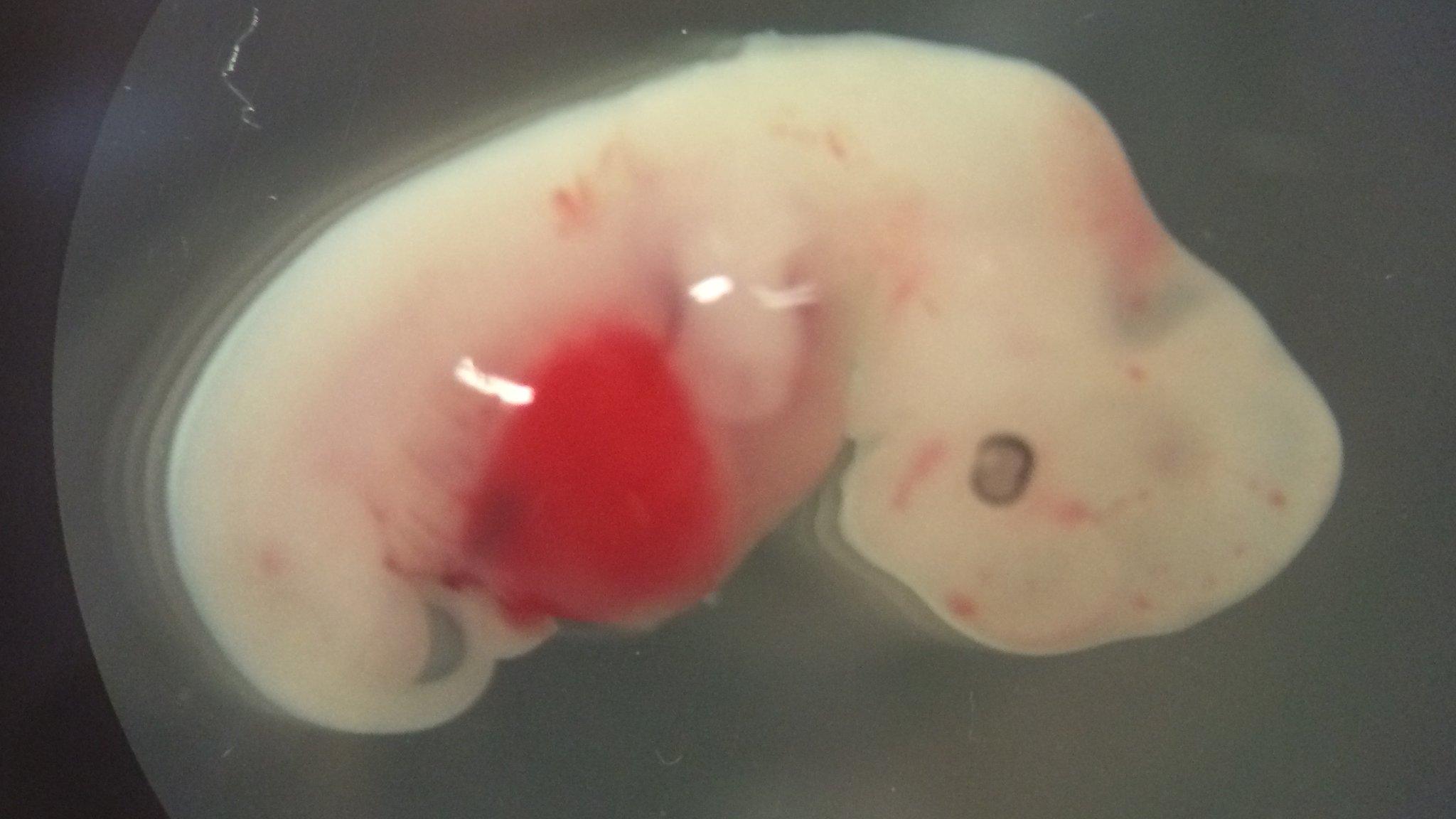

The synthetic embryo shows comparable brain and heart formation, scientists say

Scientists in Cambridge have created synthetic mouse embryos in a lab, without using eggs or sperm, which show evidence of a brain and beating heart.

The mouse embryos, developed using stem cells, only lasted for eight days.

But the research team say it could improve understanding of the earliest stages of organ development - and why some pregnancies fail.

Other scientists caution that while the technique is promising there are still many hurdles to overcome.

The researchers from the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) are the latest to publish their results in the journal Nature, external.

Researchers from Israel also published similar findings, external recently.

The Cambridge team has been studying the early stages of pregnancy for the past decade but so much of it is hidden from view in the womb.

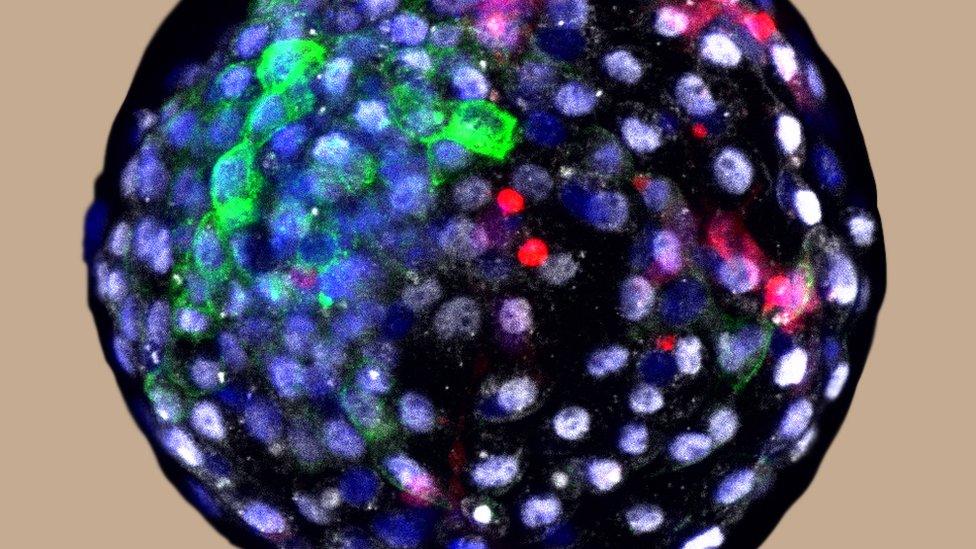

By mimicking natural processes in a laboratory, they found a way to get three types of stem cells from mice to interact and grow into embryo-like structures.

The synthetic mouse embryos only lasted for eight days, due to defects - but they reached the point where a brain began to develop.

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, professor of mammalian development and stem cell biology at Cambridge and professor of biology at Caltech, said it was "a dream come true" and could offer a glimpse into how organs are formed.

Side by side, the natural and synthetic mouse embryos looked very similar after eight days

"This period of human life is so mysterious, so to be able to see how it happens in a dish - to have access to these individual stem cells, to understand why so many pregnancies fail and how we might be able to prevent that from happening - is quite special," she said.

The advance could also mean less reliance on animals for research and a useful way to test new drugs.

'Very early stage'

However, Prof Alfonso Martinez Arias, from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, said: "This is an advance but at a very early stage of development, a rare event which, while superficially looking like an embryo, bears defects which should not be overlooked."

The researchers now plan to work on keeping the synthetic embryos developing for a day or two longer, which is difficult to do without creating a synthetic placenta.

Eventually, their ambition is to develop similar embryos from human stem cells - but this is still a long way off, and ethically much more complicated.

At present, UK law permits human embryos to be studied in the laboratory only up to the fourteenth day of development, but there are no rules around synthetic embryos.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, from the Francis Crick Institute, said that should change.

"Given the similarity with real embryos, it follows that consideration also needs to be given as to whether and how such integrated stem cell-based embryo models should be regulated," he said.

He added that it was important not to think of the embryo-like models "as being the real thing - even if they are getting close".

"If these had been derived from human stem cells, and it is accepted that these should never be transplanted into a uterus, we will never know if they are equivalent."

Related topics

- Published15 April 2021

- Published3 March 2017

- Published26 January 2017

- Published4 May 2016