'Truly remarkable' drug helps motor neurone disease

- Published

Watch Les Wood walking unaided after the treatment, in a home video from 2017

Scientists say they have slowed and even reversed some of the devastating and relentless decline caused by motor-neurone disease (MND).

The treatment works in only 2% of patients but has been described as "truly remarkable" and a "real moment of hope" for the whole disease.

One leading expert said it was the first time she had seen patients improve - but this is not a cure.

The MND Association said there was "mounting confidence" in the therapy.

MND, also known as amyotrophic-lateral sclerosis (ALS), is caused by the death of the nerves that carry messages from the brain to people's muscles. It affects their ability to move, talk and even breathe.

The disease dramatically shortens people's lives and most die within two years of being diagnosed.

Les Wood has been able to enjoy holidays in Spain with his wife again

Les Wood, 68, from South Yorkshire, was the first British patient in the international trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, external.

MND had forced him, an electrician, and his wife, Val, a nurse, to give up their careers, as walking and using his hands became more difficult.

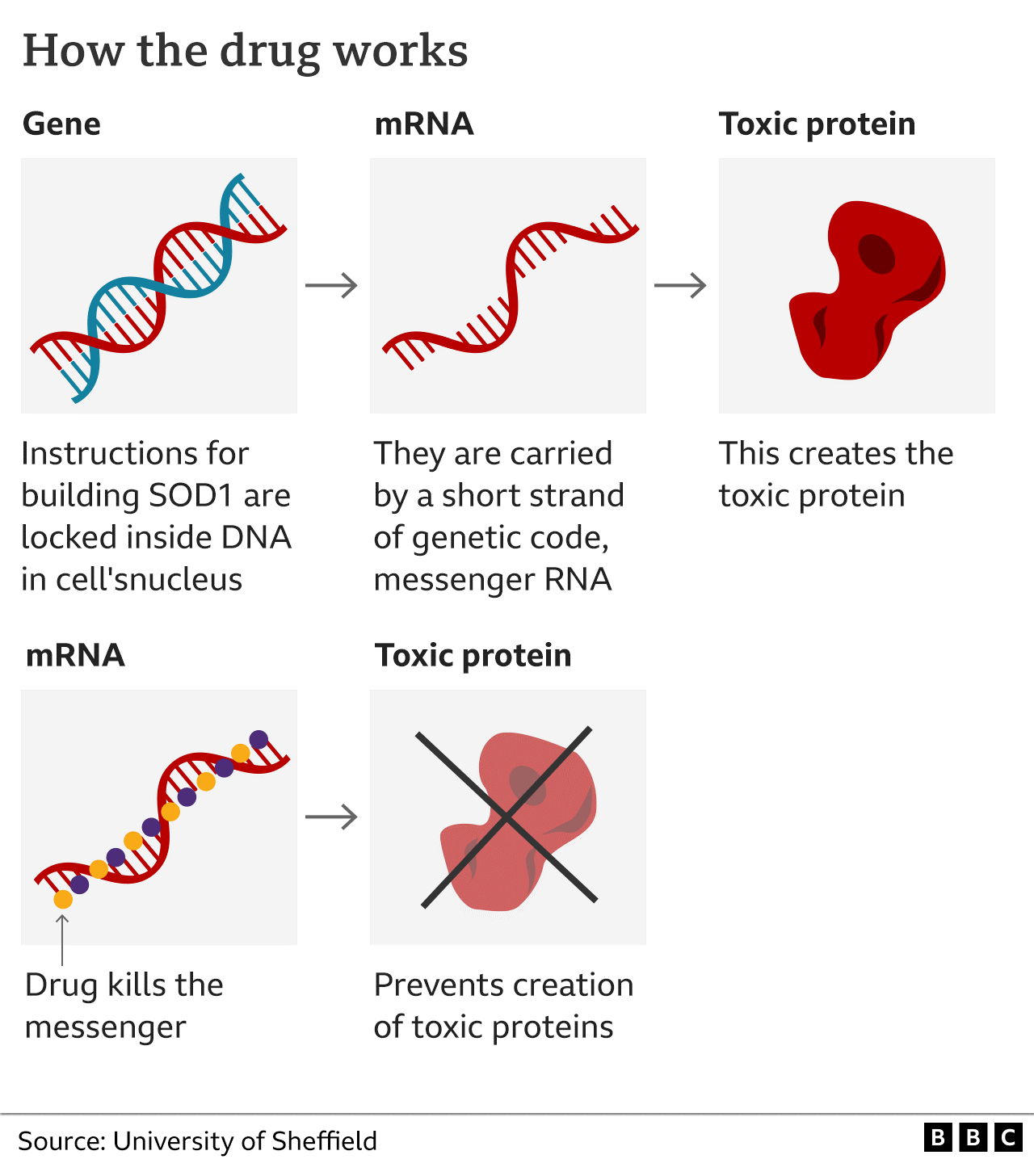

A mutation in a specific part of his genetic code leads to the production of a toxic form of the protein SOD1, which kills motor neurones. These mutations cause about 2% of MND cases but one in five of those that run in families.

The trial on 108 people, funded by pharmaceutical company Biogen, used an innovative type of medicine called gene silencing. The drug tofersen effectively mutes the defective DNA so less SOD1 is produced.

The treatment requires monthly lumbar punctures, in which a needle is passed between the bones in the spine to put the drug directly into the spinal fluid.

After six months of therapy, those getting the drug had lower levels of SOD1 but were physically no better.

After a year, however, it was slowing the pace of the disease - and some patients' symptoms improved.

Les had his first dose in 2016 - and in home videos recorded a year later, he said: "I could genuinely say, hand-on-heart, I felt better.

"I actually walked in the house, without sticks, I thought, 'This drug's working.'"

Now, he says: "MND is a progressive disease - so although my symptoms have continued to worsen, I would not be without the drug and the difference I know it has made to my quality of life."

The drug has to be injected directly into the spinal fluid

For Prof Dame Pamela Shaw, the director of the Neuroscience Institute, in Sheffield, and a veteran of more than 25 clinical trials in the disease, this was something incredible.

She told me: "This is the first where patients participating have reported improvement in their motor function - 'I can walk without my sticks. I can go up my garden steps, which I haven't been able to do for two years. I can write my Christmas cards this year, which I couldn't do last year.'"

The results were a "real moment of hope" and the start of a "new era" in which we can expect progress in other forms of MND too.

In the early stages, the researchers say, the drug is stopping further damage. It cannot lead to the formation of new motor neurones and the remaining ones may be taking a year to recover and form new connections with muscle tissue.

"It may take time for people to heal from the damage that has already been caused," said Dr Timothy Miller, the principal investigator, at Washington University.

"The vast majority of people living with ALS experience a relentlessly progressive downhill course, so the stabilisation of function is truly remarkable."

Motor neurones carry messages to nerve fibres

The treatment directly targets the fundamental cause of this type of MND so it will do nothing for the 98% of patients without the SOD1 mutation - although, it is hoped the other mutations, in more than 30 different genes, implicated could be targeted in a similar way.

"The approach used, of reducing proteins harmful in MND, is likely to have wider applications for more common types of MND," said Prof Chris McDermott, of University of Sheffield.

Tofersen is being considered for regulatory approval in the US and provided free in the UK ahead of a decision on whether the NHS should pay for it.

MND Association research director Dr Brian Dickie said the treatment had the "potential to deliver a significant benefit" for a relatively rare group of people with the disease.

The big question, he added, was whether to give the drug in the earliest stages of the disease, when it "may be even more effective", or even to healthy people with the SOD1 mutation to "prevent the onset of disease".

Follow James on Twitter., external

- Published11 June 2021

- Published3 May 2022