'I wouldn't bring a member of my family to this hospital,' says medic

- Published

Cameron Stone spent 26 hours in A&E last weekend until this bed could be found in Gloucestershire Royal

Steve Barclay is back as England's health secretary, just as the NHS prepares for what its chief executive Amanda Pritchard says could be a "very, very challenging winter".

The government has said "intensive work" is under way in the 15 most under-pressure hospital trusts in England, to speed up ambulance delays, free up beds and reduce waiting times in A&E.

The BBC has been looking at one of those trusts - in Gloucestershire - and speaking to some of the families affected.

'Chaotic'

On Friday 21 October, Cameron Stone, 20, arrived at Gloucestershire Royal Hospital by car after being referred by his GP. He had been unable to keep food and drink down for a week and was dehydrated with a painful abdomen.

"A&E was chaotic - more like a supermarket queue than a hospital," said his mother, Debbie Barnfield.

Cameron was put on a drip in A&E. Ten hours later he was moved to a small side room with other patients and given a reclining chair on which to spend the night.

"He was absolutely shattered and had a fever. All we could do was give him a towel to keep him warm," said Ms Barnfield.

The next day - 26 hours after he first arrived - Cameron was put on a trolley and wheeled into a different overspill room for the night, before being moved into the acute medical ward as a bed became free.

"I really feel for the doctors and nurses because they are literally run off their feet. I don't know who is to blame but it's an absolute shambles," said Ms Barnfield.

Cameron Stone spent the night in the overspill area of A&E last weekend

Emergency departments across the UK are struggling to quickly treat patients.

Only 57% of people who turned up at major A&E departments in England last month were seen, admitted or discharged within four hours, well below the 95% national target.

The latest figures from Gloucestershire Royal show it performs slightly worse than average, with 55% dealt with in four hours.

One medic, speaking anonymously to the BBC, said: "I wouldn't bring a member of my family to this hospital. And winter is going to be worse unless something changes fast."

'Handover delay'

Where Gloucester - like many other hospitals - really has difficulties is when people arrive by ambulance.

When paramedics try to unload those patients they are often told it is too busy and have to queue outside - a so-called handover delay.

Almost two-thirds of ambulances which arrived in Gloucester and Cheltenham last winter were stuck outside for at least half an hour, the second worst performance in England, according to NHS statistics.

Board papers show the situation did not improve over the summer.

"It's so demoralising when you're sat there waiting, hearing the calls coming in, and there are no ambulances available because they're all in your queue," said one paramedic, who wanted to remain anonymous.

"A couple of months ago, we had 30 ambulances outside the hospital, and we don't even have 30 ambulances in the whole of Gloucestershire."

Those delays mean paramedics cannot quickly get back on the road to the next patient.

The average ambulance response time for a category two emergency, such as a stroke or suspected heart attack, is now 48 minutes in England, well above the 18-minute target.

Aaron Valentine in the back of the ambulance itself, waiting for hospital admission

Aaron Valentine, 24, has Crohn's disease, a debilitating condition which affects the digestive tract.

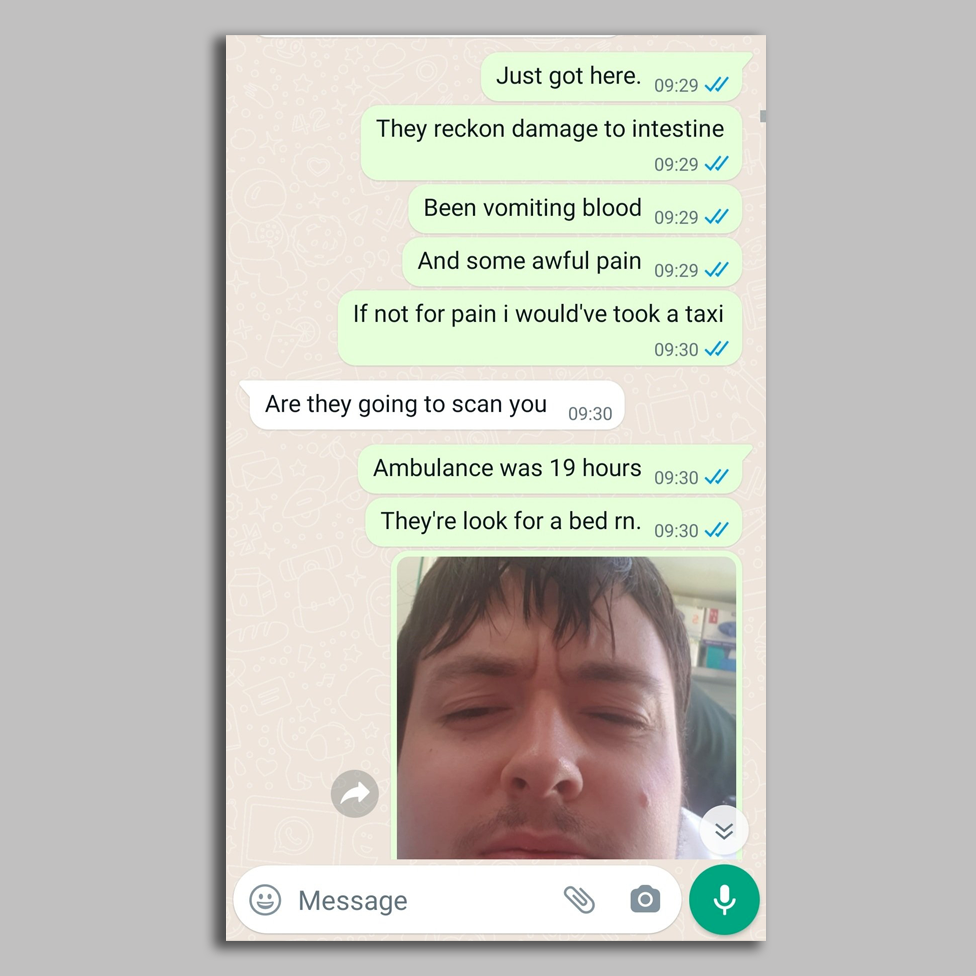

On the morning of 13 June, he started to experience severe abdominal pain. Over the next 13 hours - between 12:17 BST and 01:33 the next morning - he dialled 999 a total of five times.

"I was literally vomiting as I was on the phone and they were saying, 'we'll be there as fast as we can'," he said.

Paramedics arrived at 07:00 - 19 hours after that first call. When they got to Gloucestershire Royal, Aaron had to wait for another five hours in the ambulance, and then in A&E itself for two hours, before a free bed could be found on a ward.

"We weren't at the height of the pandemic and it wasn't a Friday night where you get a lot of drunk people," he said.

"How can the system go on when it cannot function on an average day?"

Aaron's Whatsapp exchange with his mum after he arrived at hospital in an ambulance

The BBC has spoken to two families whose elderly relatives with dementia were both held in ambulances for hours outside the same hospital.

John Thompson's 82-year-old mother had a suspected broken hip after falling in the summer heatwave.

The paramedics had to build a makeshift air-con system out of silver foil blankets to try to keep her cool for "four or five hours" between scans and other tests.

Steve Winfield, 70, died at Gloucestershire Royal Hospital in April 2022

In late April, Edna Wilson, 86, called 999 for her long-term companion Steve Winfield, 70, who had vascular dementia.

The ambulance had to wait outside, this time for more than 14 hours.

"[The paramedics] phoned me and said we're changing the mattress because he's not comfortable and he's very tired. So I just told him to close his eyes and go to sleep," Mrs Wilson said.

The next day she was called by a doctor to say that Steve had died in the hospital itself.

'A broken system'

While the situation in the south-west of England might look desperate, the region is far from a special case. Hospitals up and down the country are experiencing the same sort of pressures driven by many of the same factors.

Gloucestershire has a growing and ageing population, with admissions creeping up over time.

Its two main hospitals are finding it hard to move some of those patients out of a ward and into community or social care.

At one point over the summer, 260 of the 936 beds in Gloucester were taken up by patients medically fit enough to leave but still in hospital.

The reasons for that are complex - from NHS bureaucracy, to a shortage of social care staff, to the closure of some smaller community hospitals.

One staff member told the BBC that social care services in the region are "stretched beyond breaking point".

The result is a bottleneck - and then a backlog - that moves right through the hospital until A&E starts to fill up and those ambulances need to be held outside.

Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Trust

10.8%Vacancy rate in April 2022

4.3%rate in April 2021

9.7%England rate in June 2022

The NHS is having problems recruiting enough doctors, nurses and support staff.

In April, 11% of positions in Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Trust were unfilled, a rate which had more than doubled in a year.

This month the Care Quality Commission (CQC) downgraded the overall rating of the trust from "good" to "requires improvement", with its surgical services rated as "inadequate"., external

CQC's head of its inspection said Gloucestershire Royal was "incredibly busy and we saw the impact that staff shortages were having on the service".

The anonymous medic said there was a sense of "denial and complacency" about the problems.

"I can't wait to leave this place," they said.

A queue of ambulances waits to unload patients outside Gloucestershire Royal Hospital this year

The hospital trust's chief executive, Deborah Lee, said she was "personally devastated" to read the CQC's findings.

"I'm absolutely clear this picture has to change," she told BBC Radio Gloucestershire.

The trust said more nurses, health care assistants and social workers are being hired, and there is extra funding for more hospital and care home beds.

Like other trusts, it has started "pre-empting" more patients - moving them out of A&E into a side room or corridor of a specialist ward until a dedicated bed becomes free.

A trust spokesman said ambulance delays have "significantly reduced" this month, with an average handover time of fewer than two hours and no queues outside A&E of more than four hours.

"We know that for some patients, coming into our busy emergency departments, their experience is not what we would like," he said.

South Western Ambulance Service said it had "significantly increased" the number of crews working in the region and was embedding more paramedics directly in the busiest A&Es to speed up handovers.

The concern from staff is what happens this winter.

"We're already running at full pelt. We rarely have empty beds and if one becomes free then it's filled within a day," one nurse told the BBC.

"It's just nuts and and it's going to get worse."

A 'horrendous' night

On the night of 29 September, Wayne Cooke, who has a history of heart problems, started to suffer from serious chest pains.

The mechanic who lives in rural Gloucestershire, contacted his brother, Dean Ives, who called 999 four times between 01:01 and 01:37.

It took three hours for paramedics to arrive because, Dean was told, they were having a "horrendous night" queueing outside Gloucestershire Royal.

"I was stood by the window waiting for some blue lights thinking we might end up losing him," he said.

Wayne Cooke (l) and his brother Dean Ives at home in Gloucestershire

When help did come, the treatment was "fantastic" and Wayne was taken to Cheltenham General Hospital to have stents fitted.

He is now recovering, but Dean is thinking about the next time Wayne might need an ambulance.

"If I have to dial 999 it will be a case of 'are they going to turn up?' or 'are they going to be stuck at hospital?'."

In a statement, the Department of Health said it was investing £150m to improve ambulance response times in England and £20m to upgrade the ambulance fleet.

A spokesman said: "Our plan sets out a range of measures to help ease pressures, including an extra £500m to speed up discharge and free up hospital beds, reducing waits in A&E and getting ambulances quickly back on the road."

You can follow Jim on Twitter, external.

Have you been affected by issues covered in this story? Please get in touch by emailing: haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Or fill out the form below

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published21 October 2022

- Published19 October 2022

- Published7 October 2022