Father of girl, 4, fighting for life with Strep A infection is 'praying for a miracle'

- Published

Dean Burns, whose daughter Camila has Strep A, urged parents to get their children checked if they have concerns

The father of a four-year-old girl left fighting for her life in hospital after contracting Strep A has said they are "hoping and praying for a miracle".

Camila Rose Burns, four, has been on a ventilator at Alder Hey Children's Hospital in Liverpool since Monday.

Six children have died with an invasive form of the Strep A bacterial infection in recent months.

Dean Burns urged parents with any concerns about their children's health to "scoop them up" and to get checked.

Experts say there are more Strep A cases than usual this year.

Strep A infections are usually mild, causing illness ranging from a sore throat to scarlet fever, but they can develop into a more serious invasive Group A Strep (iGAS) infection.

Health officials confirmed on Friday that six children had died with iGAS - including five under-10-year-olds in England - since September. Hanna Roap, a primary school pupil from Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan, in Wales, has also died and her family said their hearts have been "broken into a million pieces".

No deaths have been confirmed in Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Mr Burns, from Bolton, told BBC News Camila was showing signs of improvement, but he fears "anything could take her back the other way".

In a message to other parents, he added: "Any doubts, if they don't look right, just scoop them up and take them [to seek medical advice]. Get them checked out rapid."

Dean Burns said he has been in hospital by his daughter Camila's side since Monday

Mr Burns said Camila fell ill on Saturday and was taken to hospital in Bolton the following morning, after he realised she was hallucinating.

He said her condition had deteriorated so much by Monday morning that she had to be put on a ventilator, before being transferred to the specialist children's hospital for treatment - where her family have been by her bedside since.

Describing his daughter as "our special little girl", Mr Burns said the family "just have to keep hoping and praying for a miracle so that she heals and comes back to us".

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has said the last time there was an intensive period of Strep A infection was in 2017-18, when there were four deaths in England in the equivalent time frame.

The rise in Strep A cases and deaths is most likely due to high amounts of the bacteria circulating and increased social mixing, it said.

Speaking earlier on Saturday, infectious diseases paediatrician Prof Beate Kampmann said parents should seek medical help if they were worried.

She explained Strep A caused "an asymptomatic infection in the majority of people, then there is a sore throat, then scarlet fever, and in a very, very small minority will there be invasive Group A Strep".

She said there had been three times as much scarlet fever this year than was seen pre-pandemic, adding: "It starts off with a high fever, very sore throat and very red tongue, which has this sort of papillae - eventually developing a rash which feels a bit like sandpaper.

"The rash starts in the elbows and behind the neck. It tends to then peel after about 10 days because the disease is caused by a toxin that is produced by this bacterium."

Prof Kampmann said if children became really unwell, or if parents were in doubt, they should seek help. She also said children with a fever should be kept off school.

She continued: "The good news is that Group A Strep is very, very treatable with penicillin."

But she added, "if your child is deteriorating in any way, you feel that they're not eating, drinking, being quite flat and lethargic you need to take them to the doctors and to get them checked out".

The latest data shows there were 851 cases of scarlet fever reported in the week of 14-20 November, compared to an average of 186 cases a week for the preceding years.

Watch: How common is Strep A and what are the symptoms to watch out for?

Virologist Dr Chris Smith said the general rise in Strep A infections could be due to a drop in immunity following the pandemic.

He told BBC Breakfast: "There's something about the vulnerability of the population and particularly younger people.

"What has changed is that younger people have been through three years, almost, of relative isolation from each other.

"They haven't caught the normal infections at the normal rates and at the normal times that normal children of that sort of age bracket would have done."

There have been 2.3 cases of the invasive Strep A disease per 100,000 children aged one to four in England this year, compared with an average of 0.5 in pre-pandemic seasons of 2017-19, the UKHSA said.

There have also been 1.1 cases per 100,000 children aged five to nine, compared with a pre-pandemic average over the same period of 0.3.

UKHSA advises people to call 999 or go to A&E if:

your child is having difficulty breathing - you may notice grunting noises or their tummy sucking under their ribs

there are pauses when your child breathes

your child's skin, tongue or lips are blue

your child is floppy and will not wake up or stay awake

What is Strep A?

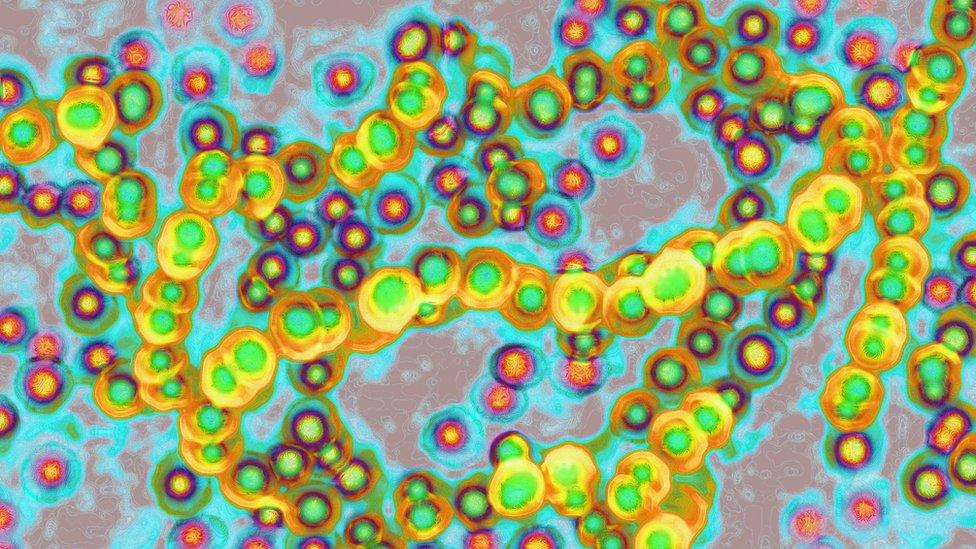

Group A streptococcal (GAS) infection is caused by strains of the streptococcus pyogenes bacterium

The bacteria can live on hands or the throat for long enough to allow easy spread between people through sneezing, kissing and skin contact

Most infections cause mild illnesses such as "strep throat" or skin infections

It can also cause scarlet fever and in the majority of cases this clears up with antibiotics

On rare occasions the bacteria can get deeper into the body - including infecting the lungs and bloodstream. It is known as invasive GAS (iGAS) and needs urgent treatment as this can be serious and life-threatening

Have you been affected by the issues raised in this story? Share your thoughts and experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published2 December 2022

- Published9 December 2022