Ambulance delays outside A&E reach new high in England

- Published

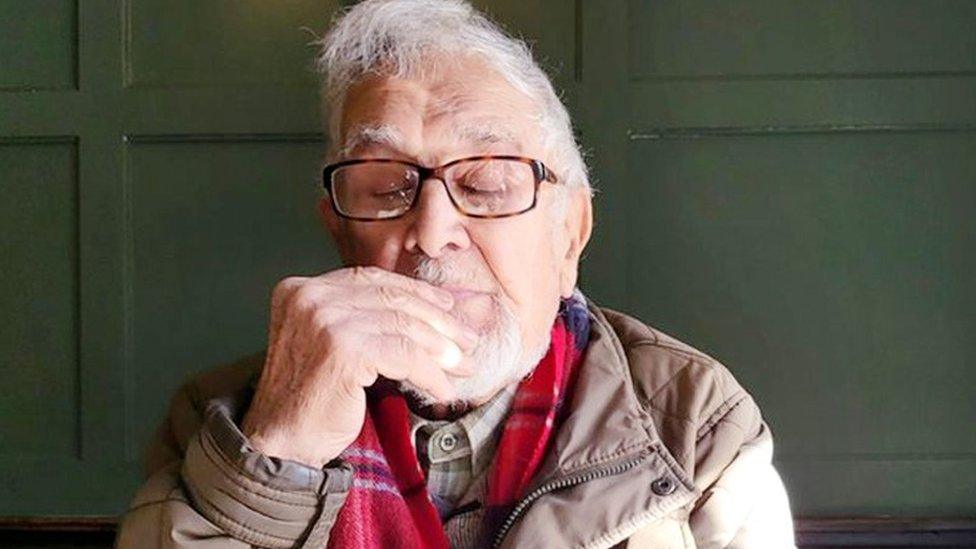

Unison members set up a picket line outside the London Ambulance Service HQ in Waterloo, London

The pressure on emergency care is greater than ever in England, latest figures show, amid fears of a spike in demand after the ambulance strike.

A quarter of ambulances, more than 16,000, were delayed for more than an hour outside A&Es - even before Wednesday's action by ambulance crews.

NHS bosses are warning of many more new patients ahead of Christmas.

And there is particular concern over those who did not seek medical help during the industrial action.

Hospitals were quieter than normal during Wednesday's ambulance strikes, but NHS bosses have said they are worried about a rebound effect, created by people turning up in large numbers after avoiding seeking help on strike days.

Meanwhile, the number of patients with flu in hospitals in England has gone up by two-thirds in one week, with calls to the NHS 111 service increasing to near-record levels as parents seek advice about strep A.

The Department for Health and Social Care said its number one priority this winter "was to keep patients safe and ensure they can access care when and where they need it".

Rising delays outside A&Es

Thousands of paramedics, call handlers and technicians took action in England and Wales on Wednesday and are set to strike again on 28 December.

Data from NHS England for the week to Sunday 18 December shows that delays getting ambulance patients into hospital for treatment are higher this month than during any previous winters.

The target for handing over patients from an ambulance to hospital staff in England is 15 minutes.

But four in 10 ambulances arriving at A&E waited at least 30 minutes before unloading patients - up from three in 10 the previous week.

And a quarter waited more than an hour (up from 17%), which contributed to 46,000 hours of ambulance staff time being lost to delays handing over patients.

The figures may explain why eight out of England's 10 ambulance services declared a critical incident on Tuesday - the evening before the ambulance strike began - because of extreme pressure.

Some are now reducing their alert level, but say they are still under immense pressure.

Thousands of hospital beds are also occupied by patients ready to be discharged, and these numbers are going up sharply every week.

'Not able to get out on the road'

Analysis by Jim Reed, health reporter

On the picket line this week, striking paramedics repeatedly raised the problem of long handover delays. And today's figures reflect that.

In England last week, a record 46,085 working hours were lost because ambulance crews could not quickly pass on their patients to other medical staff when they arrived at hospital.

One ambulance service calculates each hour lost costs £133 because crews are not able to get back out on the road to the next person who needs help.

A handover delay does not always mean waiting in the back of the vehicle - although this is often the case.

The patient may have been moved into A&E itself, but still have to be looked after by paramedics.

The new figures, though, show how difficult it has become for crowded hospitals to find space for new arrivals.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said 7,000 new real, and virtual, hospital beds were being created, and it was investing £500m to speed up the process of discharging patients from hospital into social care.

It said money was also going towards recruiting more call handlers and upgrading ambulance vehicles.

Knock-on effects

On Wednesday, only the most serious 999 calls were responded to, but there was no evidence of people going to A&E in taxis or in their own cars, NHS Providers, which represents hospital trusts, told the BBC.

Matthew Taylor, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said there had been a reduction in 999 calls on Wednesday, but an increase in people phoning 111, as well as more people being referred to out-of-hospital services.

He also shared concern over further strikes in January, saying it was the worst possible time for the NHS to be facing industrial action.

Jason Killens, chief executive of the Welsh Ambulance Service - where 50% of staff went on strike, warned of an anticipated rise in demand for ambulances after fewer people called 999 on Wednesday.

Unions had agreed that ambulance workers would respond to category one 999 calls and the most serious category two calls (emergencies, including strokes and major burns) during strikes, but there would be no guarantee of a response to less urgent calls, such as falls.

Ambulance workers in England and Wales are demanding a pay rise above inflation, which they say will improve morale and help retain staff. However, they are also protesting about being stuck in ambulances outside A&E departments for long periods, rather than attending to new emergencies.

Government ministers say most ambulance staff have received a pay rise of at least 4%, taking average earnings to £47,000. A further pay increase would mean taking money from frontline services, they add.

A plan to improve how emergency care works in England is being prepared, and will be published in January.

Nurses in England, Wales and Northern Ireland have staged two strikes this month, and have warned of more disruption in the new year unless progress is made in negotiations over pay.

Nurses in Scotland who are members of the Royal College of Nursing and the Royal College of Midwives are also set to strike after rejecting the latest pay offer of an average increase of 7.5% - an offer accepted by members of Unison and Unite.

Have you been affected by the strike? Are you an ambulance worker? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published21 December 2022

- Published21 December 2022

- Published21 December 2022

- Published20 December 2022

- Published2 May 2023

- Published20 December 2022

- Published19 December 2022

- Published1 December 2022

- Published24 November 2022

- Published16 June 2022

- Published12 May 2022