The NHS crisis - decades in the making

- Published

The NHS is in the middle of its worst winter in a generation, with senior doctors warning that hospitals are facing intolerable pressures that are costing lives.

A&E waits and ambulance delays are at their worst levels on record.

The health service was already under pressure - the result of long-standing problems - but Covid, flu and now strike action by staff have all added to the sense of crisis this winter.

So how did the NHS get to this point?

A squeeze on funding

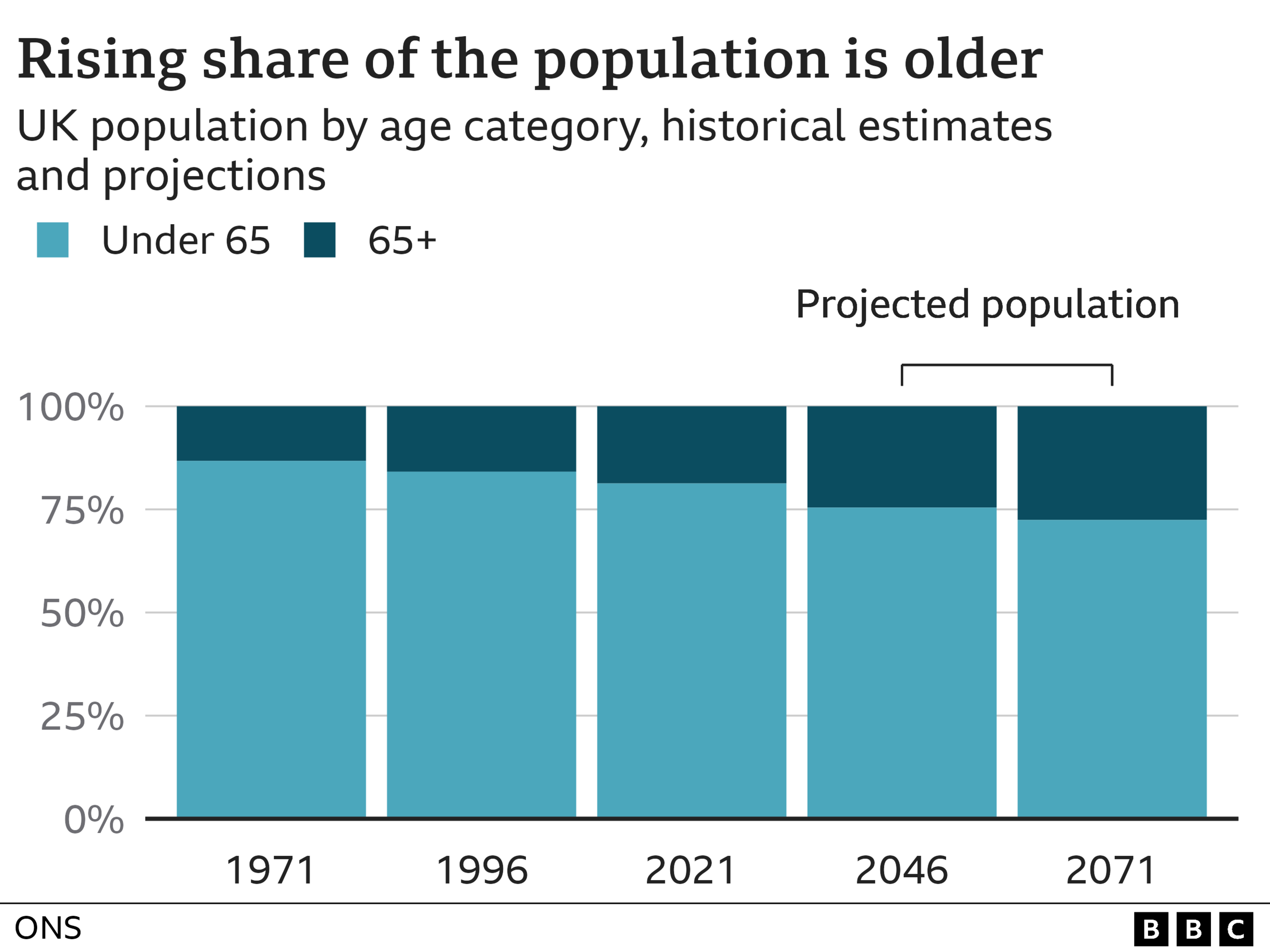

Advances in medicine over recent decades have meant people are living longer.

That is a success story. But it means the NHS, like every health service in the developed world, is having to cope with an ageing population.

That puts a huge strain on the health service. Half of over-65s have two or more health conditions and are responsible for two-thirds of all hospital admissions.

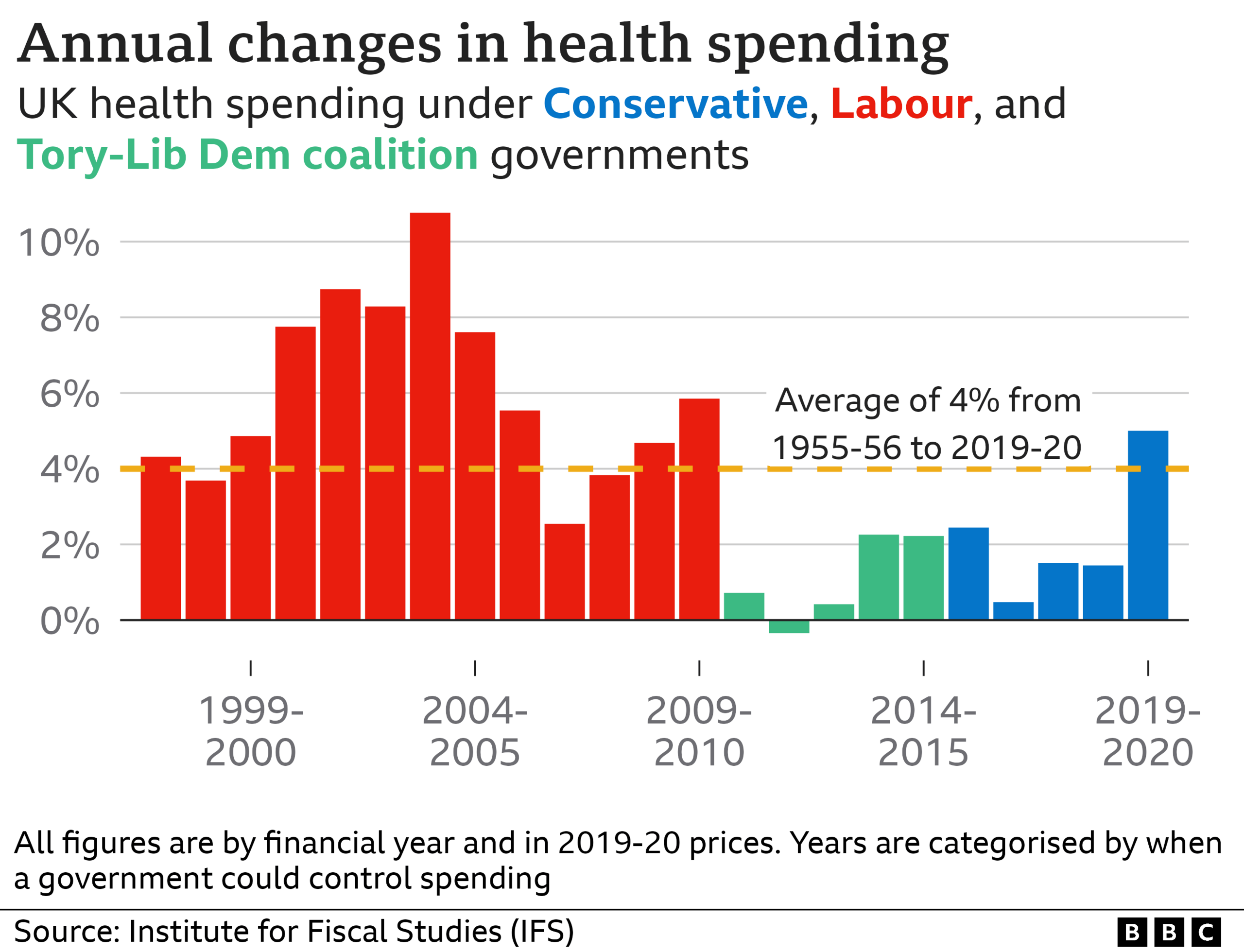

To help the health service cope with this demand as well as pay for the advances in medicine, the NHS budget has traditionally risen by an average of 4% above inflation each year.

But since 2010, the average annual rate of increase has been half that.

Of course, that is when a Conservative-led government came into power, although it is worth bearing in mind Labour were also signed up to this squeeze following the 2008 financial crash.

Labour - despite previous big increases in funding - were promising less for the health service than the Tories in the 2010 election, while in 2015 there was little between the two parties.

The government points to extra funding for the NHS during this parliament and topped up further in the Autumn Statement, external but a decade of austerity has come at a cost.

Bed numbers have fallen, while staffing shortages have increased.

The squeeze has driven industrial unrest

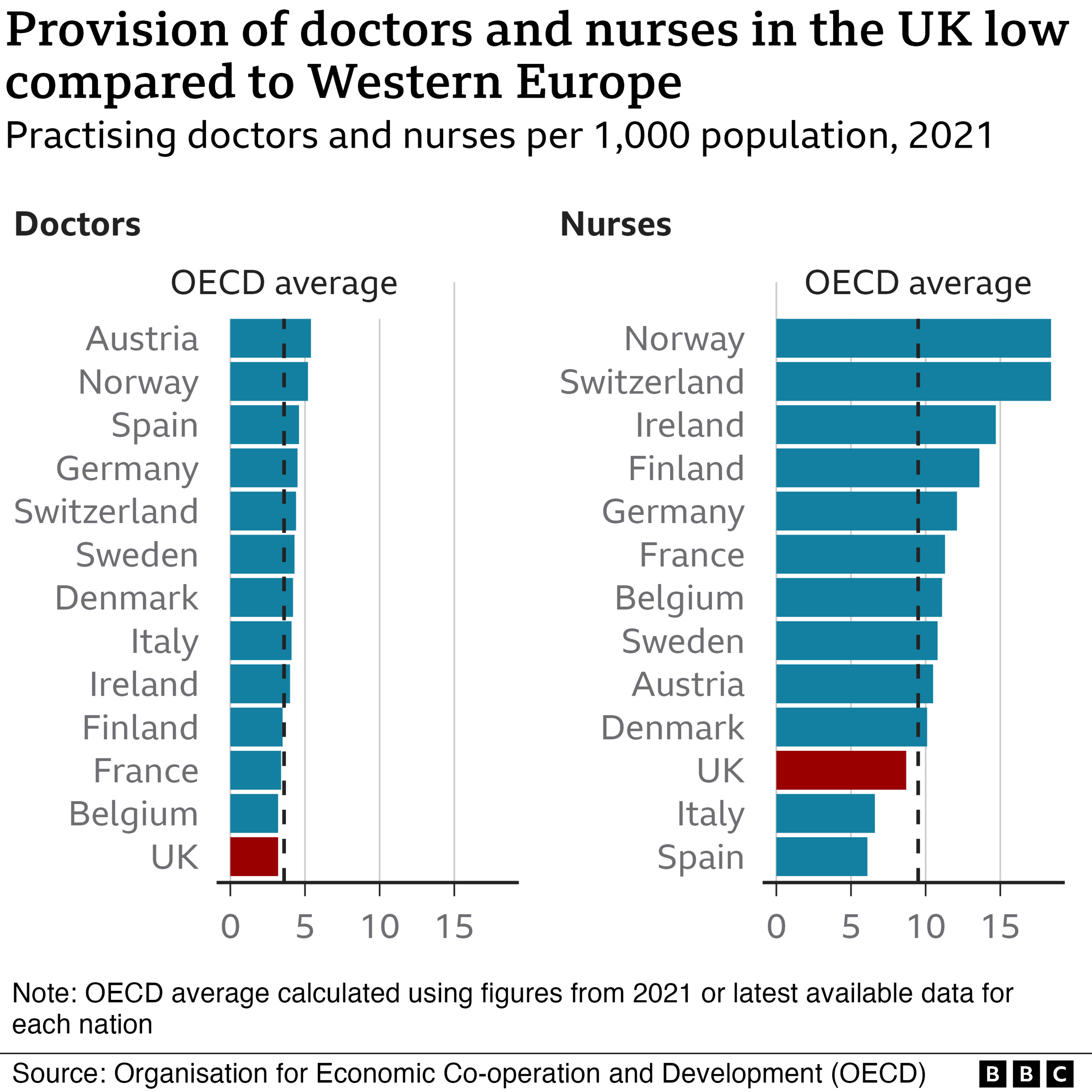

Currently around one in 10 NHS posts are vacant, leaving the UK with fewer doctors and nurses than many of its Western European counterparts.

The lack of staff puts even more pressure on those in post.

Talk to paramedics, nurses and doctors and one of the most common refrains is that the job is no longer enjoyable because they cannot provide the level of care they want for their patients.

Alongside pay, this is a driving factor for those ambulance staff and nurses who took strike action last month and look set to do so again in the coming weeks.

In fact, they argue the two issues are interlinked. Pay for NHS staff has been cut over the past decade once inflation is taken into account.

Until that is addressed, the government has little chance of plugging the staff gaps, they believe.

Social care is a big factor

The problems being seen also have their origins in when the NHS was created in the aftermath of World War II.

The decision was taken to split health (run by the NHS) and social care for the elderly (run by councils).

More than 70 years on, and despite some move towards integration, this division still persists.

This is despite successive governments since the late 1990s all promising major reform.

It means we have a health system that is free at the point of need, but a care system that is means-tested and has been squeezed even more than the NHS.

The waiting list for care is rising sharply, while this sector too has a staffing crisis with one in 10 posts also vacant.

Successive governments have failed to reform the social care system

They are two very different systems, despite being two sides of the same coin.

Without care to keep them independent, the frail elderly are more likely to end up in hospital and less likely to be able to get out.

Every day more than half of patients who are ready to leave hospital cannot because of a lack of care in the community. Not all of this is down to social care, but much of it is.

This divide is something that does not exist - certainly not to such an acute extent - in many of the social insurance systems across the world that have been developed much more around the needs of the individual.

Pressure from Covid/flu 'twindemic'

Of course, the NHS, like other health systems, has been battered by the pandemic. Waiting lists have grown and staff have been left exhausted from fighting Covid - the latter is another factor that has driven staff to vote for industrial action.

What is more, the tail end of the pandemic has had a sting. Other infections, and in particular flu, have rebounded after the lockdowns suppressed cases and immunity.

The NHS is now in the grip of its worst flu season for a decade - and this has come as the fifth wave of Covid has reared its head.

And while the most recent data suggests hospitalisations for both may have peaked, experts are urging caution because reporting delays over the festive period may have masked what is happening.

There has been another consequence too - the indirect health impacts. This is something England's Chief Medical Officer Prof Sir Chris Whitty warned about at the start of the pandemic and now appears to be taking off.

The lockdown led to people with chronic conditions not always getting the support they needed - patients with heart problems not getting statins and people with respiratory illness not getting their regular checks for example.

This is thought to be one factor behind the rising demand being seen on the emergency care system, as well as the higher-than-expected number of deaths being seen.

A frailer, sicker population is adding to the pressure when the NHS and its staff are least able to respond.

Data analysis by Harriet Agerholm

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022