Why are doctors demanding the biggest pay rise?

- Published

On Monday, thousands of junior doctors in England will start a 72-hour strike. They want a 35% pay rise. Yet doctors are among the highest paid in the public sector. So why do they have the biggest pay claim?

The origins of the walkout by British Medical Association members - the biggest by doctors in the history of the NHS - can be found in a series of discussions on social media platform Reddit in late 2021.

A collection of junior doctors were expressing their dissatisfaction about pay.

The numbers chatting online grew quickly and by January 2022 it had led to the formation of the campaign group Doctors Vote,, external with the aim of restoring pay to the pre-austerity days of 2008.

The group began spreading its message via social media - and, within months, its supporters had won 26 of the 69 voting seats on the BMA ruling council, and 38 of the 68 on its junior doctor committee.

Dr Vivek Trivedi and Dr Rob Laurenson stood for BMA election on a Doctors Vote platform

Two of those who stood on the Doctors Vote platform - Dr Rob Laurenson and Dr Vivek Trivedi - became co-chairs of the committee.

"It was simply a group of doctors connecting up the dots," Dr Laurenson says. "We reflect the vast majority of doctors," he adds, pointing to the mandate from the wider BMA junior doctor membership - 77% voted and of those, 98% backed strike action.

Among some of the older BMA heads, though, there is a sense of disquiet at the new guard. One senior doctor who has now stood down from a leadership role says: "They're undoubtedly much more radical than we have seen before. But they haven't read the room - the pay claim makes them look silly."

Publicly, the BMA prefers not to talk about wanting a pay rise. Instead, it uses the term "pay restoration" - to reverse cuts of 26% since 2008. This is the amount pay has fallen once inflation is taken into account.

To rectify a cut of 26% requires a bigger percentage increase because the amount is lower. This is why the BMA is actually after a 35% increase - and it is a rise it is calling for to be paid immediately.

The argument is more complicated than the ones put forward by most other unions - and because of that it has raised eyebrows.

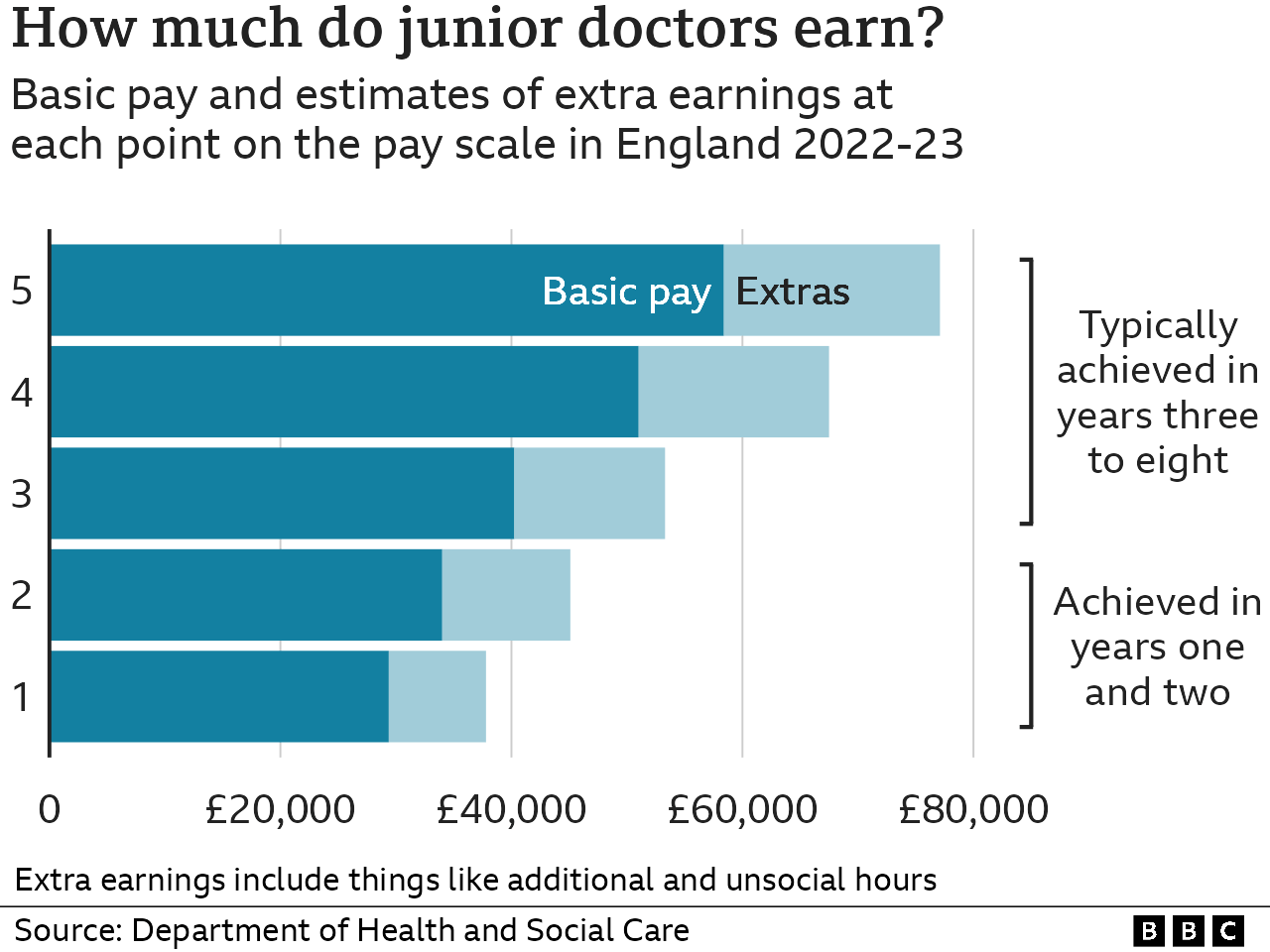

Firstly, no junior doctor has seen pay cut by 26% in that period. There are five core pay points in the junior doctor contract with each a springboard to the next. It means they move up the pay scale over time until they finish their training.

A junior doctor in 2008 may well be a consultant now, perhaps earning four times in cash terms what they were then.

Secondly, the 26% figure uses the retail price index (RPI) measure of inflation, which the Office for National Statistics says is a poor way to look at rising prices. Using the more favoured consumer price index measure, the cut is 16% - although the BMA defends its use of RPI as it takes into account housing costs.

"The drop in pay is also affected by the start-year chosen," Lucina Rolewicz, of the Nuffield Trust think tank, says. A more recent start date will show a smaller decline, as would going further back in the 2000s.

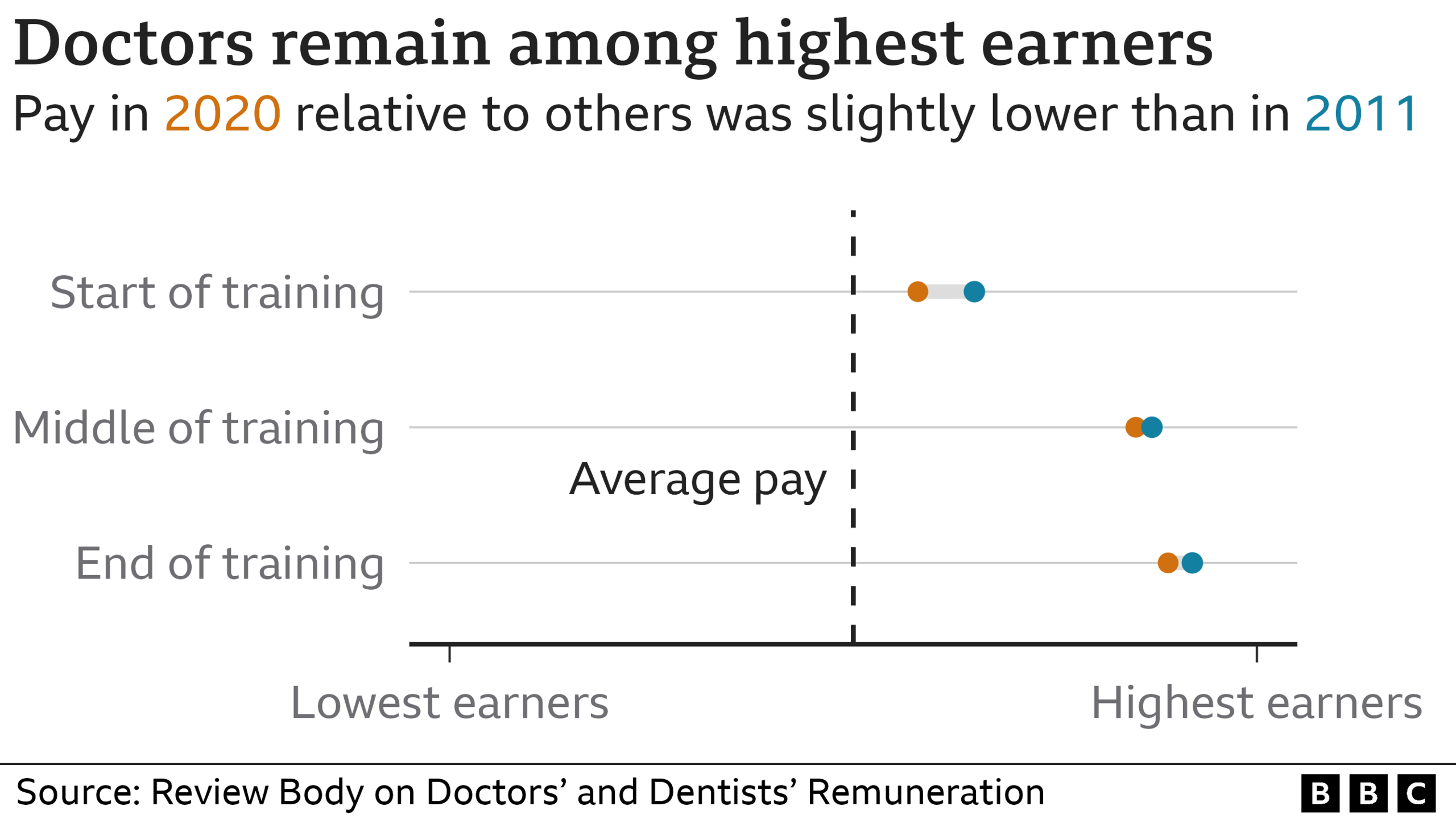

Another way of looking at pay is comparing it with wages across the economy by looking at where a job sits in terms of the lowest to highest earners.

The past decade has not been a boom time for wage growth in many fields, as austerity and the lack of economic growth has held back incomes.

Last year, the independent Doctors' and Dentists' Remuneration Body looked at this. It found junior doctors had seen their pay, relative to others, fall slightly during the 2010s, but were still among the highest earners, with doctors fresh out of university immediately finding themselves in the top half of earners, while those at the end of training were just outside the top 10%.

Then, of course, career prospects have to be considered. Consultants earn well more than £100,000 on average, putting them in the top 2%. GP partners earn even more.

A pension of more than £60,000 a year in today's prices also awaits those reaching such positions.

Little control

But while the scale of the pay claim is new, dissatisfaction with working conditions and pay pre-date the rise of the Doctors Vote movement.

Studying medicine at university takes five years, meaning big debts for most. Dr Trivedi says £80,000 of student loans are often topped up by private debt.

On top of that, doctors have to pay for ongoing exams and professional membership fees. Their junior doctor training can see them having to make several moves across the country and with little control over the hours they work. Their contract means they are required to work a minimum of 40 hours and up to 48 on average - additional payments are made to reflect this.

This lasts many years - junior doctors can commonly spend close to a decade in training.

It is clearly hard work. And with services getting increasingly stretched, it is a job that doctors say is leaving them "demoralised, angry and exhausted", Dr Trivedi says, adding: "Patient care is being compromised."

But while medicine is undoubtedly tough, it remains hugely attractive.

Junior doctor posts in the early years are nearly always filled - it is not until doctors begin to specialise later in their training that significant gaps emerge in some specialities such as end-of-life care and sexual health.

Looking at all doctor vacancy rates across the NHS around 6% of posts are unfilled - for nurses it is nearly twice that level.

Many argue there is still a shortage - with not enough training places or funded doctor posts in the NHS in the first place.

But the fact the problems appear more severe in other NHS roles is a key reason why the government does not seem to be in a hurry to prioritise doctors - formal pay talks to avert strikes have begun with unions representing the rest of the workforce

"If we have some money to give a pay rise to NHS staff," a source close to the negotiations says, "doctors are not at the front of the queue."

Update: This article was updated on 18 May 2023 to make it clear doctors can be required to work up to 48 hours and the footnote on the first chart has changed 'overtime' to 'additional hours'.

Are you taking part in the strike action? Has your appointment been cancelled or delayed? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Or fill out the form below

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022