Inside the secret talks to end nurse and ambulance strikes

- Published

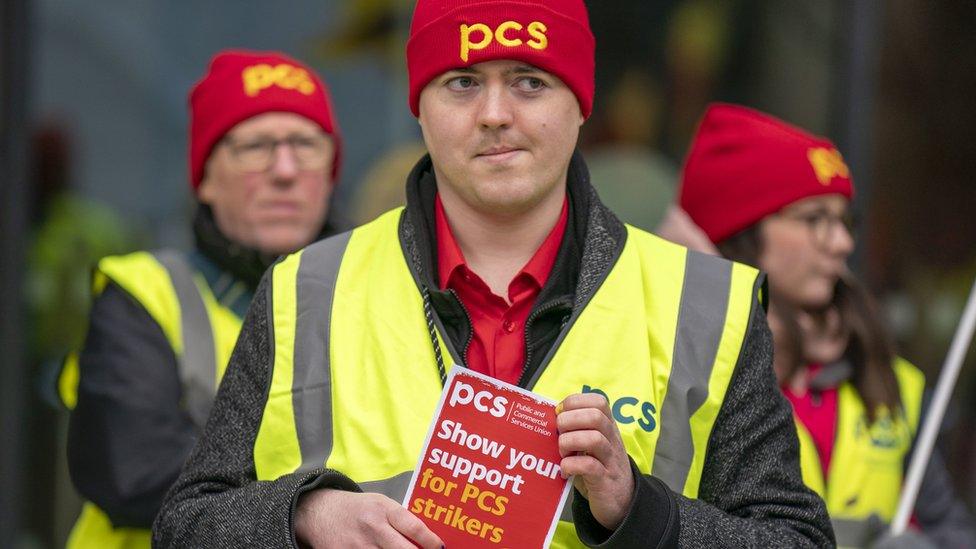

With nurses staging their most extensive strike and other unions walking out, the NHS faced one its most bitter disputes

It was one of the most bitter disputes in the history of the NHS, with the Royal College of Nursing staging its most extensive strike action ever. But as a deal with ministers was reached in England this week, the BBC can now reveal details of the secret and unprecedented talks.

On cold, frosty mornings on nurses' picket lines the rhetoric was fiery and noisy. Striking nurses condemned the government for failing to open pay talks. Ministers criticised walkouts affecting patients.

But behind the scenes it was a very different story. Secret contacts were being made between the two sides.

From early January there were confidential approaches from an unofficial source to the Royal College of Nurses (RCN), the nurses' union, about the possibility of talks beginning in England. This involved putting out feelers to see what might bring the nurses' union to the table.

Strikes by nurses and other health unions - representing paramedics, midwives and other NHS staff - had been triggered when ministers insisted on sticking to the recommendations of the independent pay review body (PRB). It had proposed average increases of 4%.

The RCN's original demand for a wage rise of 5% above inflation - equivalent at one point to 19% - was unaffordable, ministers said.

The government is ultimately responsible for setting NHS pay in England, funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. NHS Employers are involved in detailed negotiations.

But now these secret contacts had been made, it was not obvious to the RCN how closely they were linked to Downing Street or other parts of Whitehall.

The approaches seemed highly unorthodox. Usually it would be obvious whether ministers or officials were making a proposal.

But all became clear on 21 February with a call from Downing Street to the Royal College of Nursing. There was an invitation to talks which would include the idea of a one-off payment for the current financial year, a key demand of the nurses. The public announcement came as a big surprise even to some civil servants.

The prime minister was signalling a change of tack. Previously there had been denials that any more money was available. In return for the invitation to talk the RCN had to agree to call off an escalated two-day strike in England affecting all care, including emergencies.

The Royal College of Nursing's Pat Cullen had a high profile in the media and seemingly high public support

And so began the chain of events which led to last Thursday's pay offer to nurses, paramedics, midwives and other health staff in England.

There were shades of international diplomacy and intrigue in the negotiations. Back-channels and deniable contacts had steered a damaging dispute into calmer waters.

The stakes could not have been higher, as on the face of it the NHS strikes and widespread disruption had seemed destined to rumble on for months. But so far, these tentative talks were only with the RCN. The other health unions, representing paramedics and a range of health staff, were irritated. They were not invited to the table.

It seemed that the government was deliberately focusing on the nurses' union because of what seemed to be rising public support. RCN's general secretary Pat Cullen had a high profile in the media.

The RCN discussions with ministers remained shrouded in secrecy. Early encounters took place at an undisclosed location to avoid the media.

But that changed on 2 March when the other unions were invited to join the talks. Assurances were given that more money was available but the unions had to agree to keep the process confidential.

The result was an intensive series of meetings at the Department of Health and Social Care in Victoria Street, close to Westminster Abbey.

They took place on the ninth floor in offices which have traditionally been occupied by ministers. Health Secretary Steve Barclay had chosen to move down one floor to an open plan office with civil servants.

Union officials were intrigued to note they were meeting in an office once occupied by Matt Hancock. It was the scene of his kiss with his then-aide Gina Coladangelo, caught on CCTV and the images leaked to a newspaper. They joked about the possible presence of cameras.

The six members of the NHS staff council, representing the main health unions, along with one other official, were used to talks with employers. Sara Gorton of Unison, who chairs the council, says of the unprecedented situation they were in: "The process was unique in that the secretary of state was personally involved and negotiated directly with unions."

What was also highly unusual was the presence of Treasury officials as well as negotiators from NHS Employers and health staff. It seemed they wanted to keep a close watch on money being offered.

Unison's Sara Gorton said it was a unique situation for the health secretary to negotiate directly with unions

One union source said it became clear we were "negotiating with people who weren't used to it". Another added that they had "never worked in this way before".

There was a determination on the part of ministers to avoid leaks. Data sheets given to the negotiators had to be handed back at the end of each day. When the union team took the paperwork for their own private discussions they had to hand over their phones to prevent photos being taken. No paper was allowed to leave the building.

Perhaps in a bid to demonstrate Whitehall austerity there was no regular supply of refreshments. One participant remembers "coffee and an occasional biscuit". Another said they decided to bring in their own glasses for water.

For lunch they were taken down to the department's canteen, escorted at all times around the building. Occasionally they nipped out for fresh air and a quick visit to a local sushi bar.

The days were long with formal talks in full sessions interspersed with negotiating teams retreating to smaller offices. Sometimes they ran on beyond midnight. They knew the outcome of their work would be vitally important for the whole NHS in England.

Steve Barclay was present for much of the process, as was health minister Will Quince - though he had to take his leave one day because the King was visiting his constituency.

According to one union source: "Steve Barclay was constructive and there was not the heated atmosphere seen before Christmas."

One government source describes the secretary of state's style: "What gets him going is seeing a problem through - like a maths problem - he doesn't make a big noise and gets his head down."

Health Secretary Steve Barclay was "constructive" in talks, a union source said

There were tensions at times, but no serious fallings out. Late on Wednesday evening a deal was done. Exhausted participants retired, relieved but knowing it had to be sold to members.

Rachel Harrison of the GMB reflects on the outcome: "They were very long days locked on the ninth floor but it was what we asked for - we wanted to be invited in and they did."

Unions had insisted before entering the talks that it had to be "new money" which funded any pay offer. Ministers, after the deal, said the funding would not come from NHS frontline budgets.

But there is still ambiguity about the source of the money, with government sources saying some would come from existing planned Department of Health and Social Care spending and the rest after negotiation with the Treasury.

The pay dispute started with ministers insisting that they would follow recommendations of the pay review body and not negotiate directly with unions. But it was face-to-face talks which broke the deadlock.

The deal - a one off payment and a 5% pay rise for the year starting in April - included an agreement to review the composition and remit of the PRB.

Yet this is not the end of the process. The dispute will only end once health union members give their approval - and that is far from certain.

There is a separate and ongoing doctors' pay row. There are different pay discussions in Scotland and Wales.

But strikes which have caused frustrating delays for patients and damaged staff morale have for now come to an end in England. As one union source reflects: "What a shame it took so long."

Related topics

- Published18 March 2023

- Published16 March 2023

- Published17 March 2023

- Published17 March 2023