Million-year-old viruses help fight cancer, say scientists

- Published

Relics of ancient viruses - that have spent millions of years hiding inside human DNA - help the body fight cancer, say scientists.

The study by the Francis Crick Institute showed the dormant remnants of these old viruses are woken up when cancerous cells spiral out of control.

This unintentionally helps the immune system target and attack the tumour.

The team wants to harness the discovery to design vaccines that can boost cancer treatment, or even prevent it.

The researchers had noticed a connection between better survival from lung cancer and a part of the immune system, called B-cells, clustering around tumours.

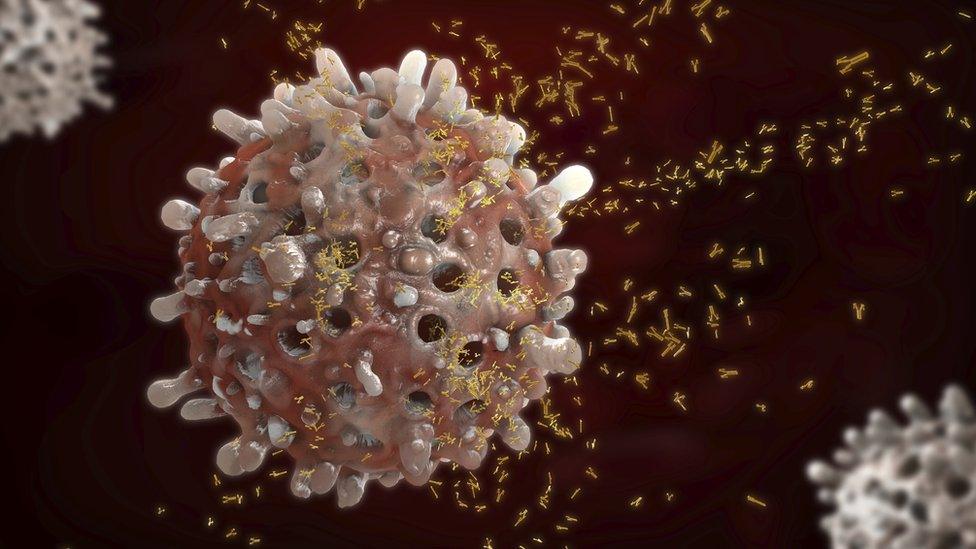

B-cells, a part of the immune system, produce masses of antibodies that can help to attack invaders

B-cells are the part of our body that manufactures antibodies and are better known for their role in fighting off infections, such as Covid.

Precisely what they were doing in lung cancer was a mystery but a series of intricate experiments using samples from patients and animal tests showed they were still attempting to fight viruses.

"It turned out that the antibodies are recognising remnants of what's termed endogenous retroviruses," Prof Julian Downward, an associate research director at the Francis Crick Institute, told me.

Retroviruses have the nifty trick of slipping a copy of their genetic instructions inside our own.

More than 8% of what we think of as "human" DNA actually has such viral origins

Some of these retroviruses became a fixture of our genetic code tens of millions of years ago and are shared with our evolutionary relatives, the great apes

Other retroviruses may have entered our DNA a few thousand years ago

Some of these foreign instructions have, over time, been co-opted and serve useful purposes inside our cells, but others are tightly controlled to stop them spreading.

However, chaos dominates inside a cancerous cell when it is growing uncontrollably and the once tight control of these ancient viruses is lost.

These ancient genetic instructions are no longer able to resurrect whole viruses but they can create fragments of viruses that are enough for the immune system to spot a viral threat.

"The immune system is tricked into believing that the tumour cells are infected and it tries to eliminate the virus, so it's sort of an alarm system," Prof George Kassiotis, head of retroviral immunology at the biomedical research centre, told me.

The antibodies summon other parts of the immune system that kill off the "infected" cells - the immune system is trying to stop a virus but in this case is taking out cancerous cells.

Prof Kassiotis says it is a remarkable role reversal for retroviruses which, in their heyday, "might have been causing cancer in our ancestors" due to the way they invade our DNA, but are now protecting us from cancer, "which I find fascinating", he adds.

The study, published in the journal Nature, external, describes how this happens naturally in the body but the researchers want to enhance that effect by developing vaccines to teach the body how to hunt for endogenous retroviruses.

"If we can do that, then you can think not only of therapeutic vaccines, you can also think of preventative vaccines," said Prof Kassiotis.

The research came out of the TracerX study which has been tracking lung cancers in unprecedented detail and this week showed cancer's "near infinite" ability to evolve. It led the researchers running the trial to call for more focus on preventing cancer as it was so hard to stop.

Dr Claire Bromley, from Cancer Research UK, said: "All of us have ancient viral DNA in our genes, passed down from our ancestors, and this fascinating research has highlighted the role it plays in cancer and how our immune system can recognise and destroy cancer cells."

She said "more research" was needed to develop a cancer vaccine but "nevertheless, this study adds to the growing body of research that could one day see this innovative approach to cancer treatment become a reality."

Follow James on Twitter, external.