Covid inquiry: The questions we really want answers to

- Published

A massive inquiry to understand the UK's response to, and the impact of, the Covid-19 pandemic, throws its doors open later. Following a statement from chairwoman Baroness Heather Hallett, a film featuring bereaved families will be played. Not one of us was left untouched by the effects of the pandemic, and we all have questions. I asked a range of people who were in the eye of the Covid storm what one question each of them most wants answered.

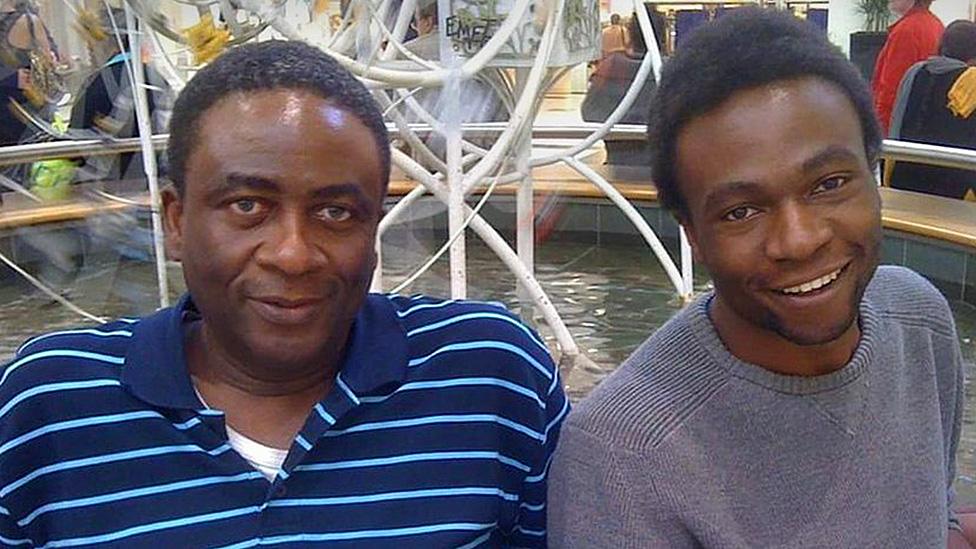

Lobby Akinnola had been due to return to his family home in Royal Leamington Spa, Warkwickshire, to celebrate his 29th birthday when lockdown began in March 2020.

Instead, he stayed at home, in London, apart from his parents and four siblings. A month later, his father, Femi, was dead.

"It changed my life forever," Lobby says. "He was isolating in the living room of our home and that's where he died. He was 60 and fit and healthy. We never expected him to die."

Lobby Akinnola wants to ensure the death of his father, Femi, and others were not in vain

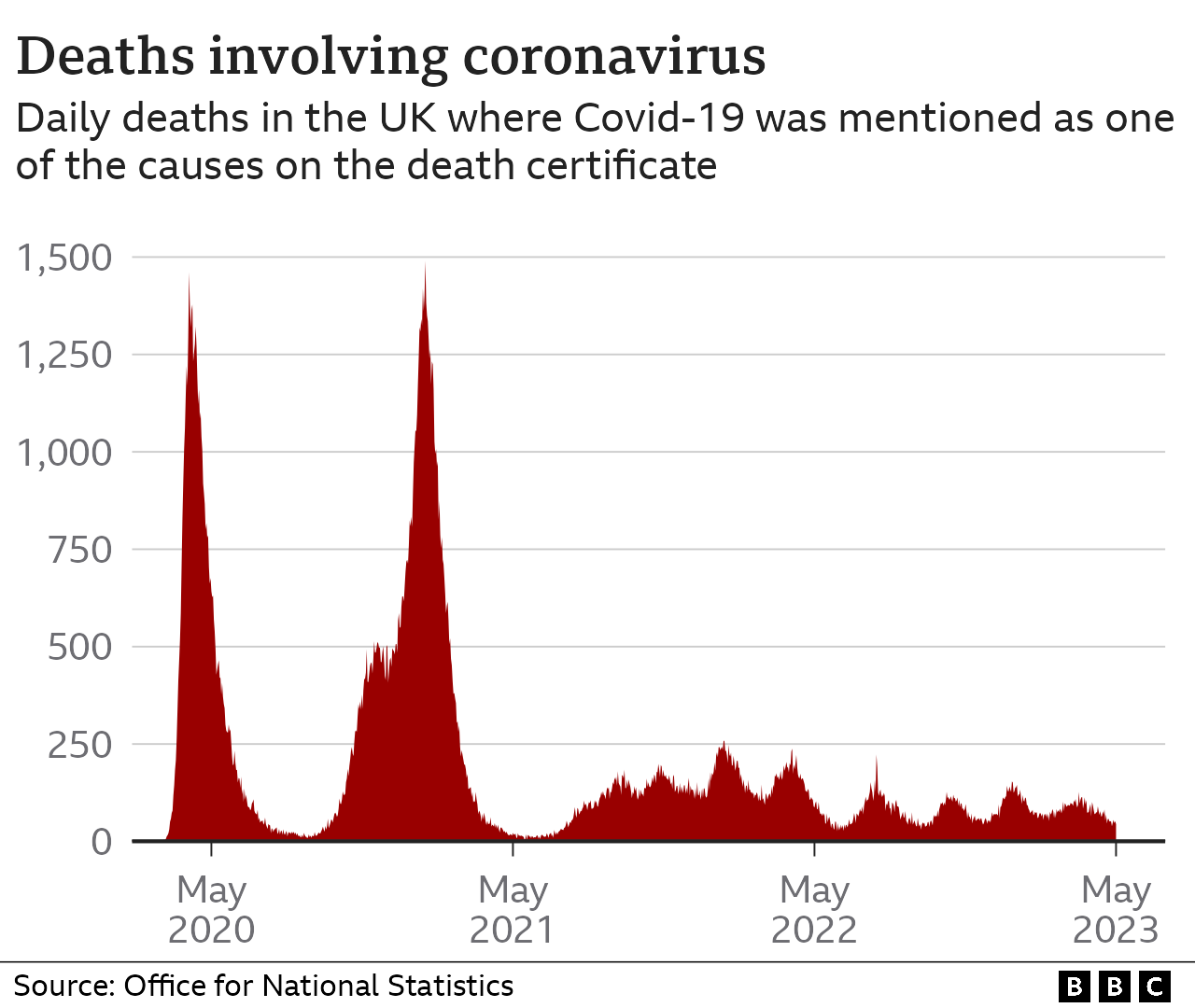

Femi is one of nearly 250,000 people killed by Covid in the UK - and Lobby, part of the Covid Bereaved Families for Justice campaign group, wants to ensure these deaths were "not in vain".

For him, the key question is: How can we better protect people when there is another pandemic?

A crucial part of that will be looking at why people belonging to ethnic minorities were at such greater risk. There is no "physiological reason" why they had worse outcomes, Lobby says. Instead, he believes it is linked to society - the jobs and housing conditions people belonging to ethnic minorities experience.

But the people who died from Covid - and those still struggling with complications known as long Covid - are not the only victims of the virus. As restrictions were imposed on the UK, at the start of the pandemic, the government's chief medical adviser, Prof Sir Chris Whitty, warned about the indirect costs. They have been huge.

Children were unable to attend school, businesses were closed, non-Covid treatment delayed and mixing banned, stopping everything from socialising to seeing dying loved ones in their final days.

The legacy of that remains, in terms of rising rates of mental-health problems, lost learning and the economic hit. It's also there in the continued high rates of non-Covid deaths and ill health as the impact of missed treatment for conditions such as cancer and heart disease materialises.

So a crucial element of the inquiry must be to look at why the government imposed restrictions - and whether they were always necessary.

One senior public health official, who played a key role in the pandemic and is due to give evidence, says it is hard to see how the first lockdown could have been avoided once the virus was here. Put simply: "We did not know what we were dealing with." But after the first wave was over and scientists understood more, the government should not have been so quick to reimpose restrictions.

In one 80-day period during autumn 2020, England went from few restrictions, to the "rule of six" limit to gatherings, tiered levels of restrictions by region, a national lockdown and back to tiers.

"We had so many rules and regulations people could not keep up," the official, who asked not to be named because of rules on what they can say in public ahead of the inquiry, says. "It was very top down and heavy handed. It goes against all the evidence of what works during disasters."

So they want to know: How did the UK get to have such complex and confusing rules?

"One of the things Sweden did was rely on the strong social consciousness of their population," the official says. "In the UK, we did not place enough trust in the public - it was damaging.

"We could have given them good information and guidance and let them act. The public showed throughout they were, on the whole, cautious and responsible." And closing schools to all but the most vulnerable children and those of key workers was the "biggest system failure" of the pandemic.

UK children spent six months remote learning, with hairdressers and pubs opening before schools in the first lockdown - a decision repeated for hairdressers in Scotland after the second UK-wide lockdown, in early 2021.

England's children's commissioner, Dame Rachel de Souza, is extremely worried about the impact this has had on children - even now, school attendance is below its pre-pandemic level.

So her big ask is: How are we going to support children to recover and avoid such harm in future pandemics?

"Where they need additional support, be that because they are worried about their mental health or because they have fallen behind at school, they want it quickly," Dame Rachel says.

Dame Rachel de Souza says children must be prioritised

"Children sacrificed so much to keep adults safe, we need to make sure we give something back - prioritising their wellbeing."

For Association of Directors of Public Health president Prof Jim McManus, it comes down one basic question: How do we avoid lockdowns in future pandemics?

"We will only do that if we are better prepared, act at the earliest stage and have good testing and contact tracing in place," he says.

"The UK and much of Europe and North America was largely underprepared for a pandemic of this magnitude - and that cost us."

The UK decided to stop community testing in late March. And in England, it took until May to launch a national large-scale contact-tracing system and September for the government to start giving sick pay to people being asked to isolate

The way care homes were supported is another topic that needs addressing.

About 40% of Covid deaths in the first few months were in care homes, as the lack of testing and personal protective equipment (PPE), heavy use of agency staff and decision to transfer, en masse, hospital patients to care homes let the virus rip through the sector.

And NHS workers want the role of austerity during the 2010s examined.

Adult nurse Stuart Tuckwood had never worked in intensive care but was deployed there to look after the sickest Covid patients during the first and second waves, working through breaks to start with because he was worried about using up the limited PPE.

"The fact I had to work in intensive care because we didn't have enough trained nurses says it all really," he says. "But it wasn't a surprise - staffing shortages were terrible in the lead up to the pandemic."

And the NHS - and other public services - cannot wait until the end of the inquiry to rectify the problems.

The first time nurse Stuart Tuckwood worked in intensive care was during the pandemic

"We need action now," Stuart says, "staff are having to strike to get the pay they need."

So his key question is: What should be done to tackle staffing shortages, so we don't face the situation again?

The wait for the inquiry is something others are worried about.

One epidemiologist who advised government during the pandemic and will also be giving evidence to the public inquiry so does not want to be named fears another pandemic could hit before the necessary changes have been made.

Some say the inquiry could well last five years.

The inquiry team says recommendations will begin next year, as it is being broken down into six different modules.

However, the epidemiologist says: "The modular approach makes sense - but some elements are going to get dragged out too long. We can't wait - pandemics happen every 10 years."

They are particularly concerned with how decision-making became skewed.

"There was no cost-benefit done on the use of restrictions which we would with other policy decisions," the epidemiologist says.

So they want to know: How should the system be changed "so we can work out the trade-offs" of the decisions we make?

"The phrase 'follow the science' became really unhelpful," the epidemiologist says. "There was no acknowledgement of the uncertainty.

"Instead, we got trapped into looking at it through a narrow lens of Covid. Even now, I am worried the inquiry has not quite got the focus right.

"If it just looks at Covid deaths in 2020 and 2021 and not what has been happening with other deaths since, the inquiry will come to the wrong conclusions. This is about more than just the virus."

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022