NHS 75: Happy birthday - but can it survive to 100?

- Published

- comments

The NHS turns 75 on Wednesday, but the landmark anniversary has been greeted with dire warnings it is unlikely to survive until its 100th birthday without drastic change. So what is the solution? From sin taxes to cutting back on medical treatment for the dying, experts have their say.

When the NHS was created the main focus was on short bouts of treatment for injury and infection, but now the challenge is completely different.

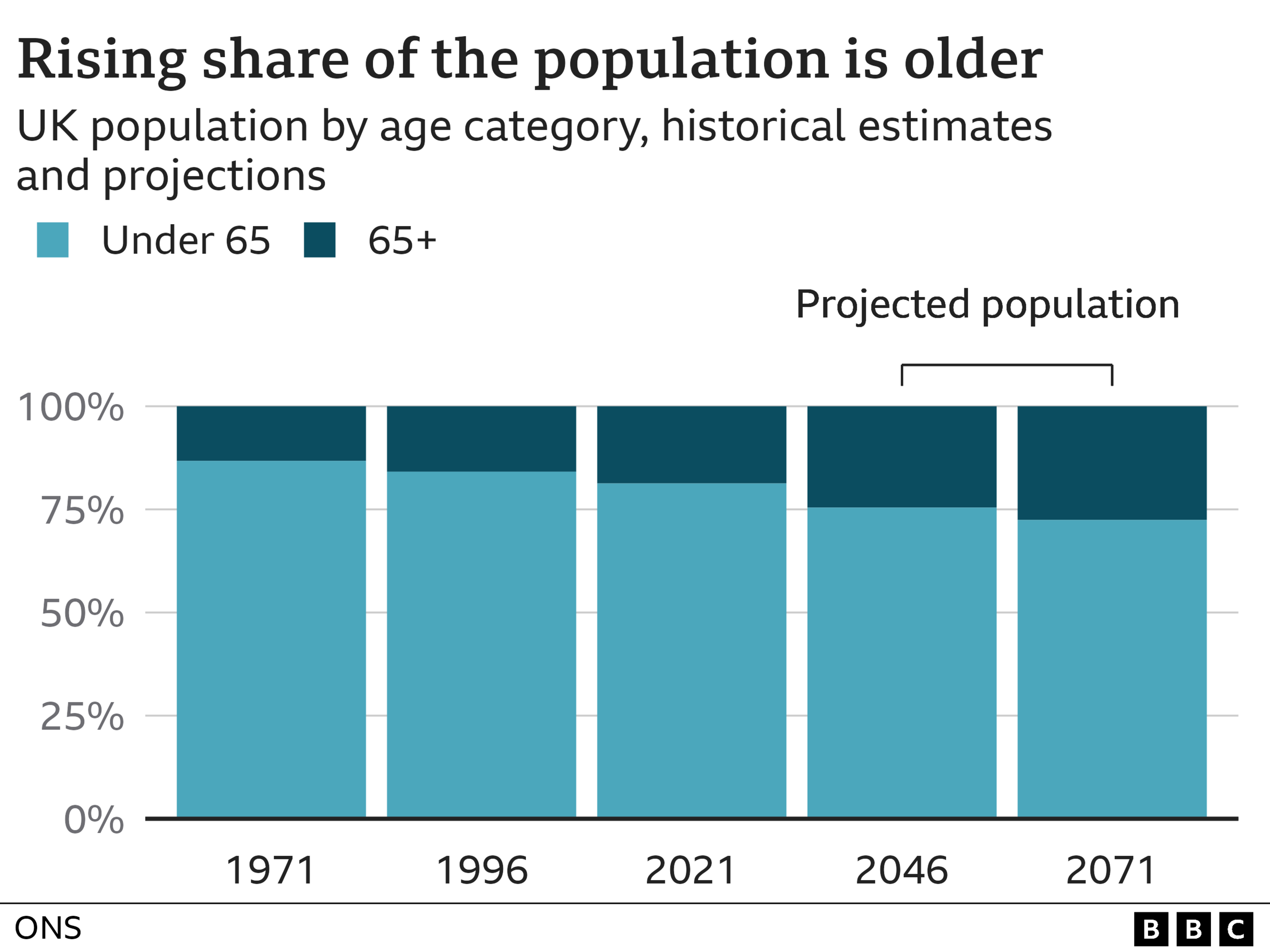

The ageing population means huge numbers of people are living with chronic health problems, such as heart disease, dementia and diabetes that require long-term care and for which there is no cure.

It is already estimated about £7 out of every £10 spent in the NHS goes on people with these conditions. On average, those over 65 have at least two.

Listen to The NHS: Who Cares podcast series with Dr Kevin Fong as he explores the challenges facing the NHS and looks for solutions.

And the situation is only going to worsen. "The numbers are going to grow," Health Foundation director of research and economics Anita Charlesworth says. "The baby boomer generation is reaching old age.

"Their health is going to be shaped by the lives they have lived - and they are a generation that have lived through the rapid increase in obesity. Their ill health is baked in. The next two decades are going to be very challenging."

Increases in the NHS budget will be needed but this must be accompanied by a shift in how resources are distributed, she says, so more is spent "upstream" in the community, including on social care, which sits outside the NHS, and prevention, to help people better manage their conditions without hospital care.

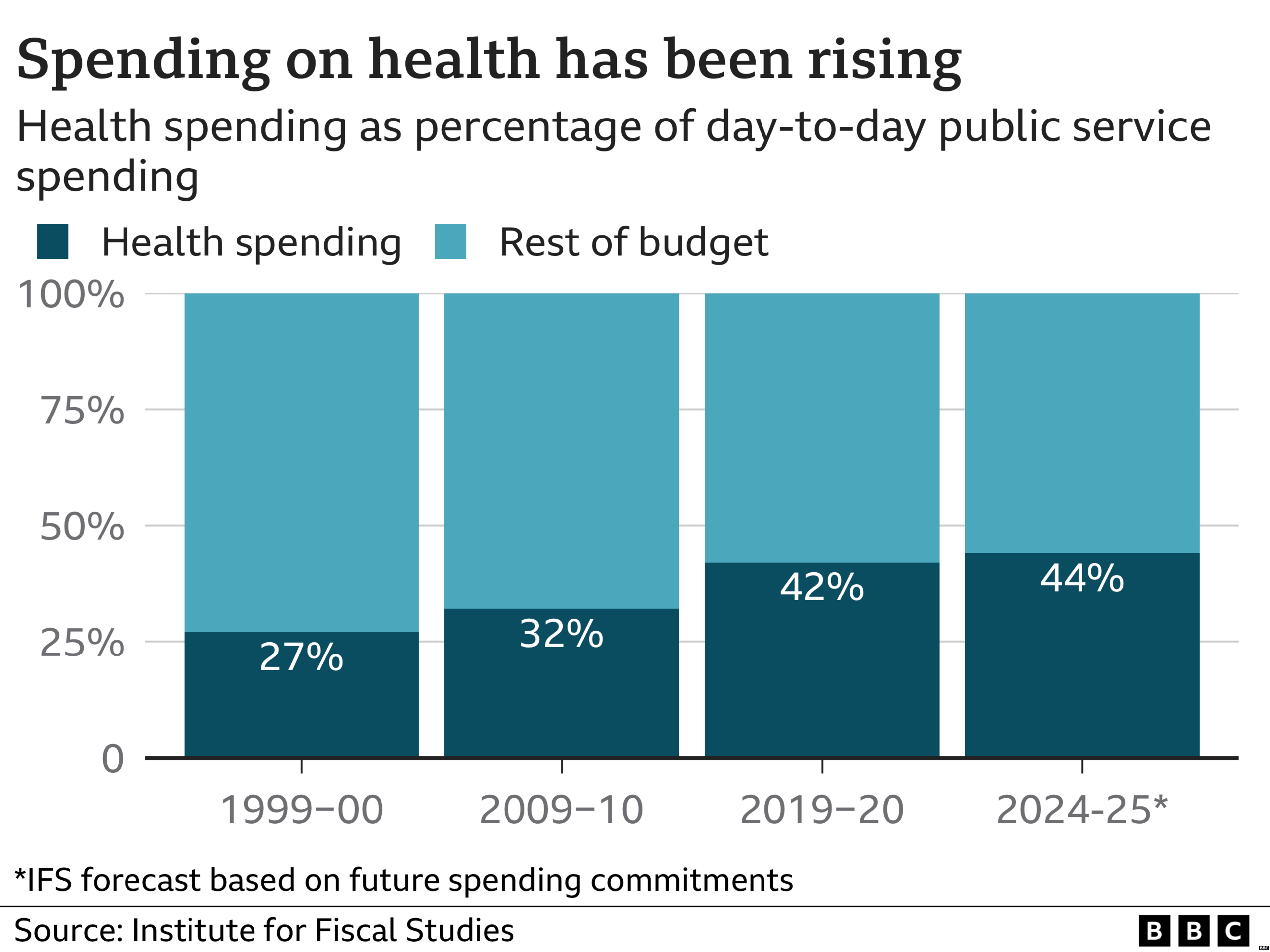

But given the amount of public money spent on the NHS has been rising ever since the health service was created - it now accounts for more than 40p out of every £1 spent on day-to-day public services, once things such as welfare are excluded - many are asking whether such spending is sustainable.

Former Health Secretary Sajid Javid, who has floated the idea of charging to see a GP, arguing the NHS should be willing to learn from the approaches adopted by other countries, has called the current direction of travel "unsustainable".

But Ms Charlesworth, who used to be director of public spending at the Treasury, says extra money can be found, pointing out countries around the world are having to do the same.

"This is not unique to the the UK and our system," she says. "It is a global phenomenon. But increasing investment in the NHS is going to require economic growth - without that, you have to cut other services or increase taxation."

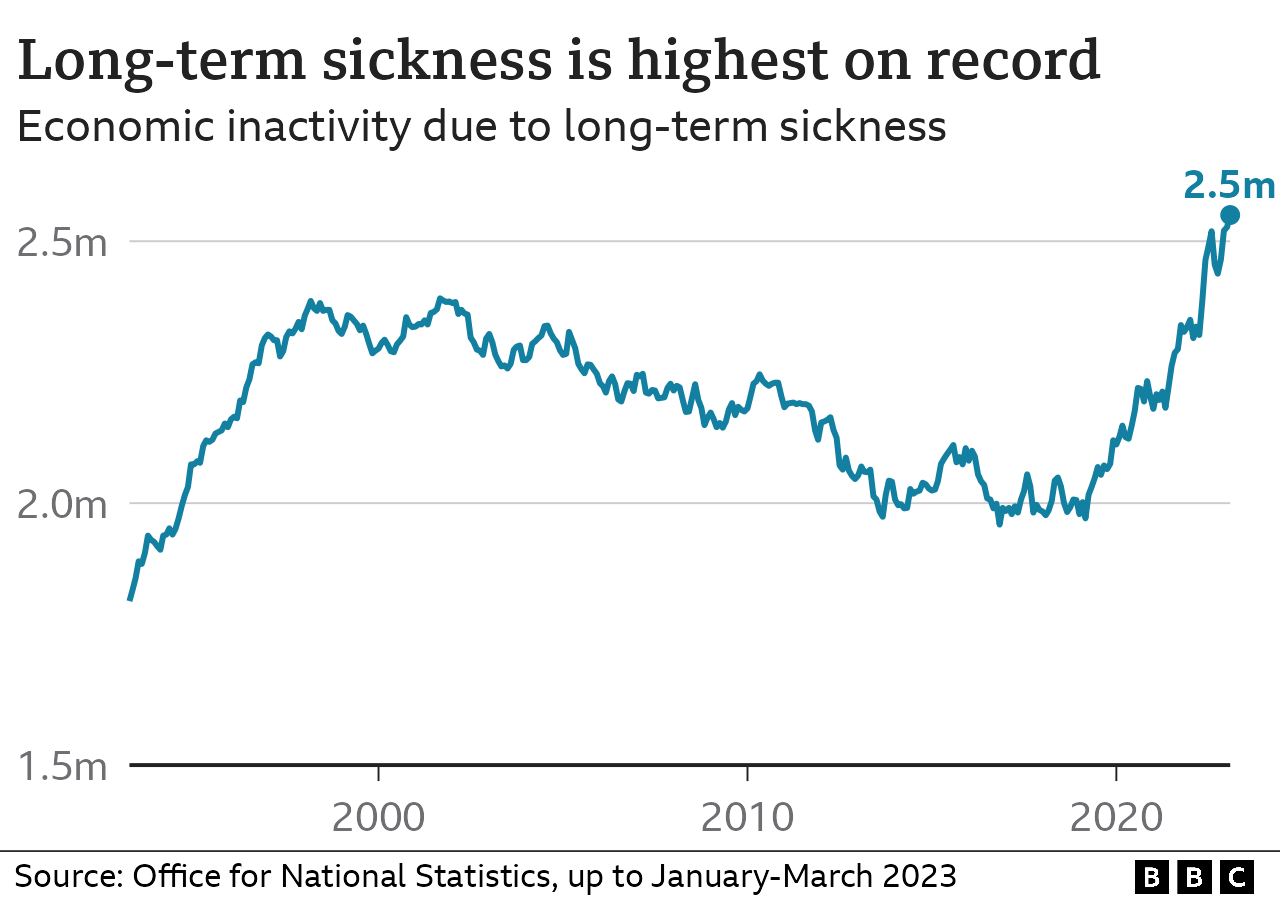

Healthcare spending should be seen as an investment in the country, rather than a cost, Ms Charlesworth says, pointing to data showing 2.5 million people are out of work because of poor health - equating to one person off long-term sick for every 13 in work.

"Economic growth depends on good health," she says, "but at the moment, we have got too many people on waiting lists - and there is a particular problem with mental health too."

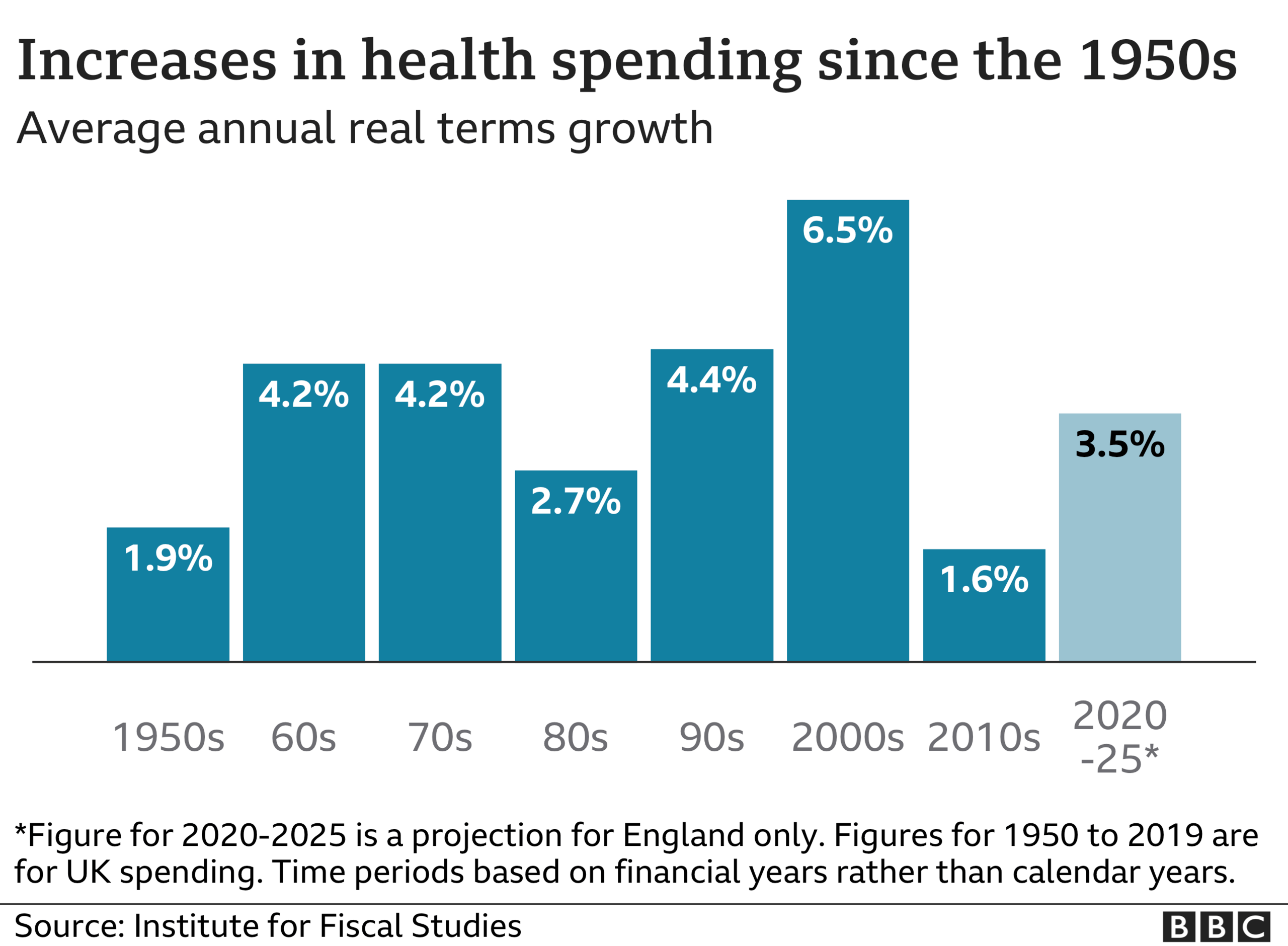

King's Fund chief policy analyst Siva Anandaciva, who recently produced a report for the think tank looking at how the NHS compared with other rich nations, says as much as 5-6% extra a year may be needed in the short-term to tackle the immediate problems with the backlog and ageing infrastructure - the boost to the workforce announced by the government last week will take years to have an impact.

His report showed how the NHS had fewer staff and less equipment such as scanners than many other comparable countries - and to those who suggest a different model of funding may be needed, made it clear the findings were not an argument for moving to another system, adding there was little evidence any one particular approach was inherently better than another.

"History tells us that we do need to spend more on the NHS," Mr Anandaciva says. "Anything less than 2% is managed decline - and what we are spending now 3-4% is just standing still."

He says that will likely mean investing a greater proportion of public spending on the NHS, but says digital technology can make savings in other spending areas whereas the NHS is heavily reliant on labour. "At some point you will need a nurse to provide care," he adds.

Life expectancy gains since the NHS' creation have not been matched by increases in healthy life expectancy - on average, people are now expected to spend more than 20 years living in ill-health, according to the Office for National Statistics, external.

"We had hoped that medical advances would lead to people both living longer and living longer in good health - but that has not happened," Mr Anandaciva says. "It will require us to become much more active and healthier."

Many of the factors that influence the way people live are outside the NHS' control, he says. These so-called social determinants include education, work, housing and neighbourhoods.

Mr Anandaciva would like to see employers in particular more involved in the health of their workforce and backs the use of "sin taxes" such as minimum pricing for alcohol and levies on sugar and salt to influence behaviour.

But he says there will also need to be an honest debate on where to prioritise that spending. "At the end of life, our use of healthcare gets more intense and costs more," Mr Anandaciva says. "Would money be better used elsewhere?"

It is a point also made by Prof Sir David Haslam, who used to chair the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, which decides what treatments should be made available on the NHS.

Sir David, who has written a book, Side Effects, about the challenges facing the NHS, says there needs to be more focus on getting "most bang for our buck".

There is too much focus on drugs and treatment that simply extend life rather than services that support people to live in good health, he says.

"For example, research has shown seeing the same GP for years reduces hospital admissions significantly," Sir David says. "If that was a drug, we would hail it as a wonder treatment - but instead, we've watched the number of GPs fall."

'Poor co-ordination'

He says the medical profession overall is too "super-specialised" and calls for more generalists in the community and hospital to treat "the individual rather than their organs".

"It's so wasteful - patients with six or seven conditions can spend all their time going to different hospital departments, seeing different people, often with poor co-ordination between them," Sir David says.

And he also questions the amount of medical intervention at the end of life.

"Too many frail elderly patients are dying in hospital when that may be a completely inappropriate place," Sir David says.

"We have over-medicalised the end of life. When I die, I want to be in the place that is my home, with good care being provided. This is not about rationing care, it is about providing rational care."

Related topics

- Published5 July 2023

- Published5 July 2022