Our Future Health boss defends big pharma 'conflict'

- Published

Sir John Bell believes that without commercial companies, many scientific breakthroughs would never happen.

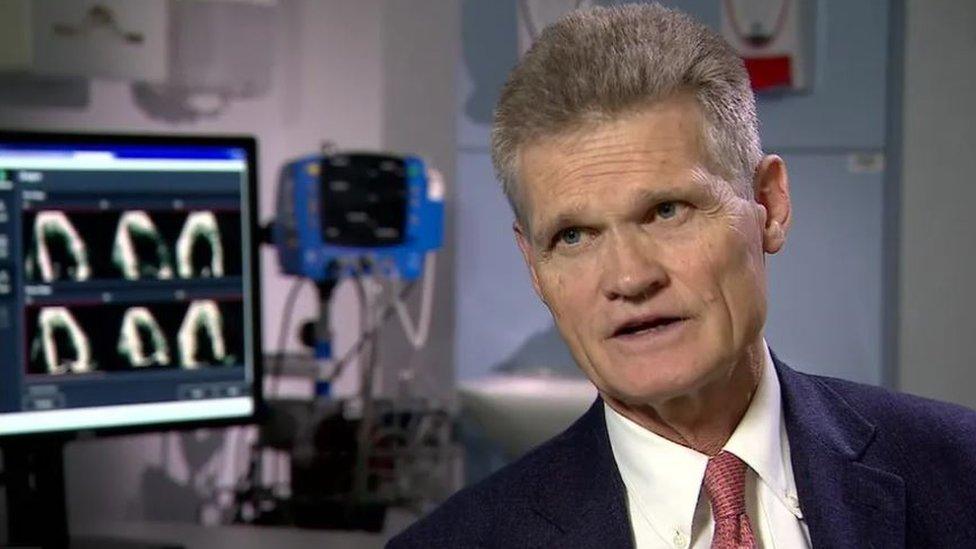

A scientist overseeing an NHS project to genetically test millions of patients has defended having a financial stake in its partner drug company.

Our Future Health chair Prof Sir John Bell has £773,000 of shares in Roche.

He told BBC Radio 4 he did not think his shareholding was relevant.

But the executive director for Genewatch, a not-for profit group that monitors genomics has questioned the potential "conflict".

Funded by the government and the health industry, Our Future Health (OFH), external is a national study set up to analyses people's genes and lifestyle to prevent disease.

It recently enrolled its millionth volunteer, and it is hoped five million adults will eventually sign up.

The study's aim is to find better ways to prevent, spot and treat illnesses like cancer and dementia early on.

It is collecting health and genetic data to create a long-term archive of health information.

Radio 4 asked Sir John if he felt comfortable with having such a stake in Roche and if he is influenced by it.

He said: "No, I don't feel anxious about that at all...I spent 20 years on the board of Roche and I'm no longer on the board.

"I don't think is is a material issue to the discussion and I don't feel at all anxious about that being a conflict."

Genewatch's Dr Helen Wallace said she is especially worried that companies involved with OFH may try to influence it to promote huge NHS investment in mass genetic screening that could do "more harm than good".

"Genetics has lots of important applications in health, for example, diagnosing genetic disorders in children, looking at the genetic changes that happen in a cancer," she said.

"But what we're concerned about is a push to collect the genome of every healthy adult and try to predict the diseases that you're going to get."

She added :"There are spin-out companies like Genomics PLC from Oxford University, which wants to try and interpret what the genetic information means for your future health.

"And then there are all the big technology companies that want to store the data and do their own analysis.

"In practice, different companies, different research groups give you different answers."

OFH involves collecting health and genetic data and creating a long-term repository of health information

Sir John is one of the leading professors of medicine at Oxford University and played a crucial role in the pandemic as part of the team developing the Astra Zeneca Covid-19 vaccine.

Dr Wallace told Radio 4 documentary The Screening Dilemma that she thinks "people like Sir John Bell have too many conflicts of interest".

"People like him have commercial interests that make it hard for people to believe that they will always act in the public interest, rather than the interest of the drug company.

"So it potentially could undermine public trust in the decisions that could be made by Our Future Health."

He said he was the government's Life Sciences Champion and has work with a number of biotech companies over the years but also said there was no denying the role commercial interests play in the health industry.

"If you think the drugs we all use for all these diseases occur because somebody has waved a magic wand and they appear on the table - that's not the way it works.

"This is why you need people who understand the industry. You have discovery, science going on in academia - funded often by government charities. It then gets picked up by biotech companies and larger commercial ventures.

"That's the that's the kind of ecosystem in which we all live. If you take any one of those bits out, the ecosystem doesn't work."

Health correspondent Matthew Hill underwent testing with Our Future Health in Swindon

As part of the documentary The Screening Dilemma, health correspondent Matthew Hill volunteered to have his blood taken by OFH in a portacabin in Swindon, Wiltshire.

I arrive at a Tesco car park in Swindon. This week the millionth person signed up to OFH, and I expect part of its initial success has been to make it convenient for people to come for these tests.

I'm here to have various blood tests done as part of the study.

I am struck by how busy the the waiting room -s, with several patients of varying ages and ethnicity willing to take part. Their motivation seems to be generally altruistic.

One woman called Sue tells me: "It's to check on my own health and it's more for my future health, for my grandchildren.

"They look at your DNA and it could prevent something for them in future."

Another woman says: "It's a really good project that can help eliminate things along the line before it gets too late."

Phlebotomist Jamie tells me as she takes my samples: "As far as I am aware they will be looking at some genetic markers.

"You will be offered some feedback in the future, but it could take up to two years."

On its application form OFH asks me if I'm happy to grant access to my health records.

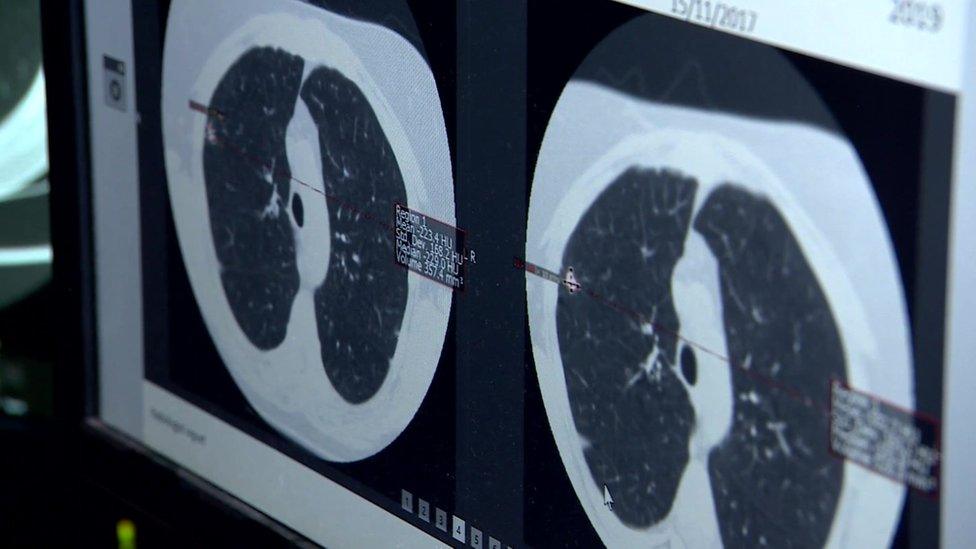

I'm informed it will try to carry out genome sequencing on my blood.

It says: "In the future, we will get in touch to ask if you would like to receive personal feedback from your samples, DNA or other data. You might learn new information about your health or risk of disease from this feedback.

"We will always give you more information and the chance to ask questions before you make your decision, and you can say yes or no.'"

OFH will use genetic testing to look for the early stages of major chronic diseases, trying to identify risk factors in order to understand the factors that are associated with early pre-symptomatic disease, particularly in young people.

Those running the study says it aims are to better treat and prevent common diseases in future, by providing a research database to scientists around the world of up to five million UK individuals genome.

They may also provide those that take part with an individual genetic risk score, like some of the private tests do, however, the exact process for this has yet to be decided.

But while the study could help provide invaluable health data, Dr Wallace still has concerns.

"Most scientists know these tests are poorly predictive of your health, and that means they won't help to prevent diseases," she said.

"Instead, we should be looking at public health, tackling poor diets, stopping smoking, tackling pollution, those are the things that will make a difference to our future health."

Sir John said he agreed tackling lifestyle issues is vital, and said things like blood pressure and cholesterol are an important part of the OFH feedback.

GeneWatch said it is also concerned about allegations made in 2021 that Lord David Cameron, who was then a private citizen, was "lobbying" on behalf of Illumina, the genetics company he worked for.

It had been reported that he encouraged Health Secretary Matt Hancock to speak at a conference co-hosted by Illumina, shortly before it won a £123m government contract in 2019.

According to the Times, external, Lord Cameron wrote to Mr Hancock personally to recommend he attend the conference.

Cameron was cleared of wrongly lobbying Illumina, external, which has 80% of the market share of the industry of DNA sequencing machines.

His spokesman confirmed both men had attended the conference and the former Prime Minister also mentioned his attendance at the conference on his X account.

Mr Hancock's office rejects any suggestion that he responded to lobbying by Illumina and previously stated that "he had no involvement in the awarding of these contracts and all normal processes were followed".

'Pioneer'

There is no suggestion of wrongdoing in how the contract was awarded.

A spokesperson for Lord Cameron said: "Lord Cameron's former role with Illumina was approved in November 2017 by the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA) and their guidance is published online.

"This took account of the relationship between Illumina and the UK Government / Genomics England.

"Lord Cameron has always been clear that he has never been involved in any contractual negotiations related to Illumina's work, nor did he ever seek to influence the Government on Illumina's behalf."

Sir John told Radio 4 that while he was not involved in that process he believes that Illumina was awarded the contract because at the time, it was the only company that had demonstrated the ability to do sequencing at "the cheapest price, and the highest quality".

Sir John is keen that the UK is seen as a pioneer of screening.

And it's true to say that a lot of money has been invested by private industry to get this system of screening right.

But there are concerns among geneticists that giving this kind of feedback, known as polygenic risk scores can do more harm than good.

Oncologist and international cancer advisor, Dr Paul Cornes, said: "It's required billions of dollars of capital and lots of very clever people to be funded to work in these programmes, bringing in genomics and AI, to develop screening tests, and that capital needs a return on investment.

"So there are many people who have an interest in promoting this ahead of the data, which is why, particularly this month, there has been so much concern signalled by medical associations worldwide."

They believe it is essential that the pros and cons of such testing are weighed up by experts from the UK National Screening Committee (NSC).

In a statement the NSC said it: "looks forward to seeing the results of any robust research in the hope that it can influence screening policy recommendations."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published6 November 2023

- Published24 October 2022

- Published11 August 2021

- Published9 November 2020

- Published2 January 2018

- Published30 July 2019