Don’t call me urban! The time of grime

- Published

- comments

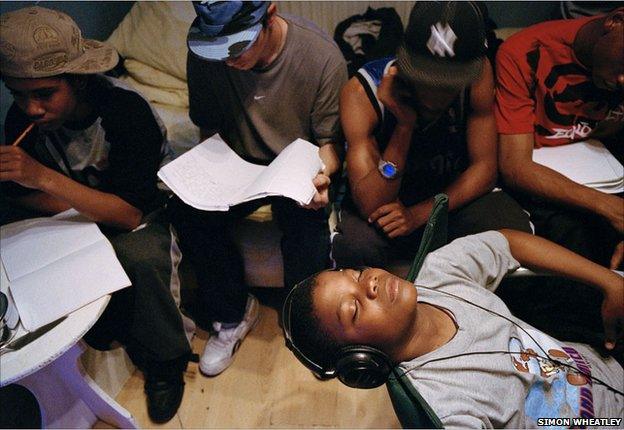

Simon Wheatley: "Jammer's basement studio. This was one of my first assignments for RWD magazine. The Guardian ran an interview with him a year or so back and referred to his studio as grime's Abbey Road, so I’m pleased it's in the book."

Hooded youths on street corners, dealers and gangstas, but this is not New York, this is London in the 21st Century, a city that spawned grime, a new genre of urban music, external from its deprived inner boroughs.

Yet grime artists were caught in a paradox, on the one hand associating with the glitz and materialism of US hip hop and on the other the reality of life on under-funded housing estates, many of which were no longer fit for purpose.

Photographer Simon Wheatley has dedicated more than 10 years to documenting the grime scene in London, capturing the lives of those whose futures would be shaped by their involvement in the movement.

Some of those he met, such as members of grime music collective Roll Deep, have emerged into the mainstream as significant artists. But there are others who also command large and dedicated followings and yet remain out of the media spotlight.

Of course there are those who have moved away to forge new lives and sadly some who lost theirs during the turbulent years of postcode wars, external.

Wheatley's pictures just ooze a feeling of isolation and the tension within many of the frames almost reaches out and grabs the viewer. Wheatley states that: "The title of the work is inspired by the discrepancy that exists between the 'cool' perceptions of black culture on the one hand and on the other, the often-harsh reality of actually being born black on a London council estate."

Yet the project didn't start out that way. It began life as a study of council estate architecture of the late 1960s and early 1970s - architecture that was being pulled down all over the capital. Wheatley said: "I found the idea that architecture that was seen to be rather 'futuristic' had been unsuited to the future that had followed, and I found that paradox rather interesting - as well as the social dynamics of urban regeneration, particularly the effects on the less affluent."

The project took him to Lambeth Walk, an area that was struggling with unemployment and massive change as the once thriving street market became little more than a few traders hanging on to their pitches, external. Here he spent time with many older people who felt trapped in their homes, afraid to go out. But alongside this he was photographing youths in the area and realised that those pictures were stronger.

He said: "I became aware that what I was witnessing in terms of the anti-social behaviour of some of the youths was becoming an epidemic in London, and that this was an important time to continue documenting. A generation earlier youngsters had been respectful of their elders but this seemed to have changed."

The project may not have progressed beyond this had his initial architecturally-inspired pictures of Lambeth been picked up by a magazine as he would then have moved on to something new. But the work remained largely unnoticed and so he carried on the project switching from medium format to 35mm as the project progressed.

The critical part of the work, as with any project, is of course access. Introductions were a key part of the process and what ultimately led to the project's success. Wheatley explained: "The first 'gang' of youths I photographed were youngsters who I had seen growing up on Lambeth Walk. They'd also seen me wandering around with an old camera and probably just thought me a bit odd, certainly not a threat as an undercover cop.

"I'd hang around them for short periods of time until they got bored of me being there, when they could get dangerous. It helped that one of them had a brother who was a DJ I'd done some work for but that only went so far.

"Later on, after I'd moved to east London and was documenting the grime scene that had burgeoned there, things became a lot easier in terms of access. I was recognised as a music photographer as I had been working for underground music magazine RWD, external, and the youths would be pleased to have me around, knowing that I'd shot this or that crew.

"North-west London was also welcoming enough after the singer NY, external introduced me to some people from Street Life Kings (SLK). Generally, there were some who would always remain suspicious of who the strange chap with a camera might be and I'd know when to leave. Once down in Kennington things got really heavy. That was a bit later, in late 2007, when I'd become complacent about the access I'd been enjoying with my music connections.

"But Peckham was really hard to get into. People were convinced I was undercover down there. That was towards the end of the project when the youth violence in London was becoming an ever-younger phenomenon and I was keen to explore the world of the 13-15-year-olds.

"But while a 16-18-year-old might be seriously alienated and negative, I could still reason with him in some way, his mind was capable of digesting me. But I found that the younger youths whose minds were less evolved lived in a world of pure hype and it was very hard to reason with them.

"In the end I got the pictures I felt the book needed after Lewisham opened up and someone's younger cousin helped me negotiate parts of the Pepys estate in Deptford. I remember seeing an eight-year-old boy hanging out one winter's evening with the crew I was photographing and I was thinking 'wow, it's getting even younger, I need to see that too,' but that was really at the end of my project. It was time to get the book out there, and hopefully contribute something to the debate on the issues of London's inner-city youth."

Photographer Simon Wheatley's exploration of the grime music scene in inner-city London is on show at Rich Mix in Bethnal Green Road, external, London, until 24 June.

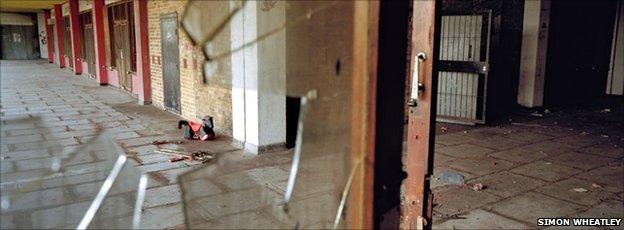

Simon Wheatley: "With a friend who knew the area well I climbed over the breeze blocks to photograph the decaying, soon-to-be demolished remains of a notorious housing estate in North Peckham. It was the area where Damilola Taylor had been killed, and the little rocking horse was like a haunting reminder of a lost childhood."

Simon Wheatley: "On a housing estate in E3 a girl, whose street name was 'Tomboy', was a 16-year-old MC about to go to jail where she'd deliver the baby she's carrying. For a long time I’d look at this picture and wonder what happened to her and to her baby, but I’m happy to say we're back in touch now and that she's become a good mum."

Simon Wheatley: "This portrait of Crazy Titch has become an iconic grime photograph. Some people see the book and say 'oh, you took that picture,’ but really it was just a throwaway shot on the end of the roll. Crazy Titch went to jail on a 30-year sentence, and for many he was 'the' grime MC."

Don't Call Me Urban! The Time of Grime by Simon Wheatley is published by Northumbria University Press.