Behind the contact sheet

- Published

- comments

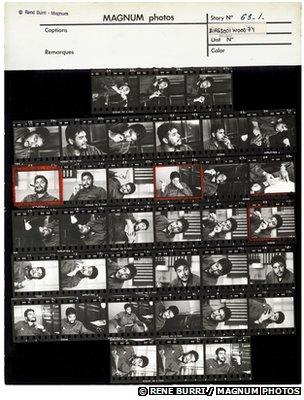

Rene Burri's photograph of Che Guevara was taken during a two hour interview in New York in 1963

The contact sheet is often described as the photographer's sketch book. It is the result of those moments of exploration, moments spent waiting for a scene to develop before the final moment when, 'click', you know you've got the shot in the can.

The godfather of photojournalism, Henri Cartier-Bresson is famously known for analysing other photographers' contact sheets as a means to judging their work.

You can learn so much from what is left out from a final edit as well as seeing how the photographer explored their chosen subject. Although Cartier-Bresson used to cut up his own contact sheets, preserving only those that worked well as sequences or the best individual frames.

The out-takes also remove a little of the mythology around the final image as it begins to show what else was happening around the moment of capture. And that's no bad thing. They also offer the photographer a chance to discover something new when revisiting those sheets many years later.

A new book from the archives of the Magnum Photo Agency brings together 139 contact sheets by 69 photographers, each one accompanied by the thoughts of the photographer.

Here are a few that caught my eye whilst flicking through.

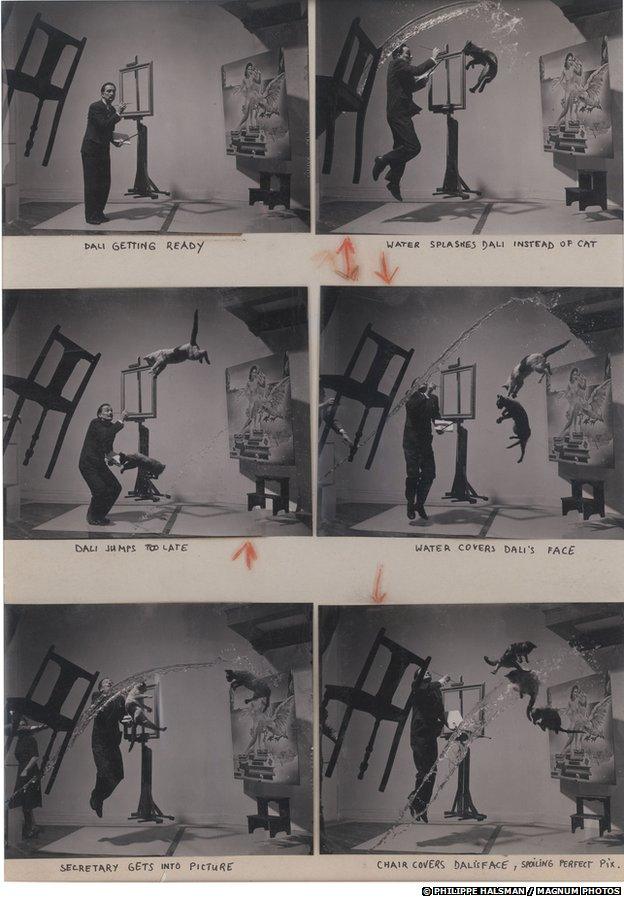

Philippe Halsman: Dali Atomicus, 1948

Halsman's photograph of Salvador Dali, external is well known and captures something of the surrealist spirit of his work. Viewing it now, when pictures like this are edited via the computer screen, it is fascinating to see the frame slowly build to the final composition. Each out-take contains a small note below the picture of the fault within it.

The photograph was taken in Halsman's New York studio with a 4x5 twin-lens reflex camera designed by Halsman. The picture required four assistants plus Halsman's wife to co-ordinate the various aspects of the picture. Halsman wrote at the end of the shoot: "My assistants and I were wet, dirty, and near complete exhaustion - only the cats still looked like new."

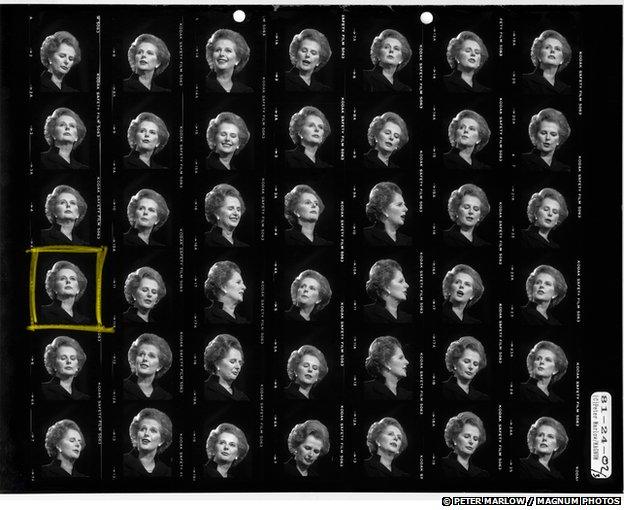

Peter Marlow: Margaret Thatcher, 1981

In 1981 Margaret Thatcher was prime minister, Britain's first and so far only woman to occupy the post. It was a time of huge change within the country and one that, for good or bad, shaped the decades to come. Marlow was a young photographer with the Sygma agency at the time, on assignment for Newsweek.

He had a Rollei flash on his Nikon F2 and "simply blasted away during Thatcher's speech, hoping to get that one shot". He notes that he was one of around 10 other photographers shooting the speech: "Forgetting the politics, she was always friendly and open to the photographers who were with her, in a way that would be hard to imagine today."

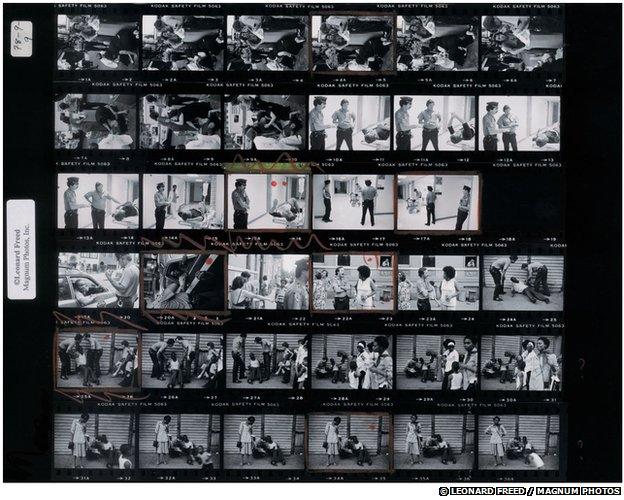

Leonard Freed: Police work, 1978

There are a few stand out frames on this contact sheet by Leonard Freed, but 15a is the one that is most interesting in terms of the build up of events to the captured moment and indeed afterwards. It is a nothing scene, then bang, one moment where victim and police officer inhabit the same moment, then it is gone.

Freed was working for The Sunday Times on a story on violence in New York. Freed's initial shoot took a wide swipe at the theme, but London got in touch and told him to find, "more blood and gore". So he went out and photographed more than 50 murders.

Yet Freed's eye was drawn to the police officers, asking why they do what they do? He writes: "I didn't want to be against them, to show brutality. I was not a spy..."

Of the contact sheet, he adds: "Contact sheets are a waste of money. I find 99.9% of the frames on the contact sheet are mistakes one makes while photographing. Because it is a waste of money, I love them. There are things in life we must do just because we find them unprofitable. Also, contact sheets are private: they belong to me, whereas photographs, once they are out of my hands, take on a life of their own."

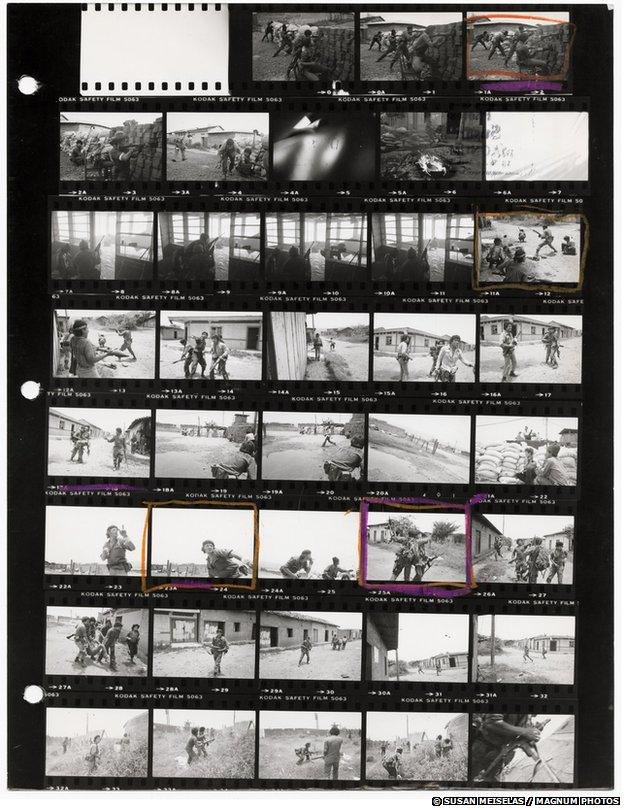

Susan Meiselas: Sandinista, 1979

Susan Meiselas's pictures from Nicaragua are a remarkable document of an old fashioned revolution. Working with two cameras - one loaded with black and white, the other with colour film - she initially became frustrated at being unable to get to where she knew the story was.

Soon though, she had made the necessary contacts and as she worked realised that this was a story that needed to be told in colour. It was a time when newspapers still printed in black and white, indeed colour was very much the domain of the commercial and art photographer. She writes: "Some critics thought it romanticised the young Sandinistas and glamorised the conflict. For me, the black and white became like a sketchbook, because I could process it locally."

The unprocessed colour rolls would be dispatched, by hand to Managua, then to Miami, and eventually to New York, where they would be processed by the Magnum office.

Frame 23a here shows "Molotov Man", famously depicted in colour, external, and a picture that came to symbolise the revolution. Meiselas notes: "I never used a motor drive so, as you can see... I nearly missed the dramatic moment, between the frames of the two Leicas I was using at the time."

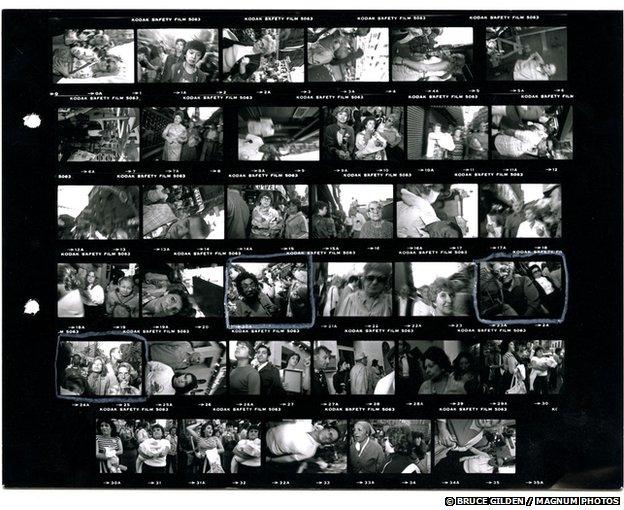

Bruce Gilden: San Gennaro street festival

Bruce Gilden is best known for his close-up street photographs of New York, often mixing flash with daylight which added an aspect of tension to each frame. He writes: "The reason I started using flash in the early 1980s was because I had previously shot 600 rolls and wasn't satisfied. When I added flash, I found that it highlighted the subject... and allowed me to show speed, stress, anxiety and the energy of the city."

There are a few frames that make the cut on this contact sheet of pictures from the San Gennaro street festival of 1984. In frame 20a he was drawn to a boy on the shoulder of a man, which he thought to be a "living collage of New York". In another, 24a, it was two women seemingly unaware of their surroundings, that caused the shutter to be pressed.

Each new contact sheet offers the photographer a chance to reveal something missed, Gilden believes. "I am a tough editor of my work and usually when looking at my contacts I find I can go as many as 50 rolls without getting a good photo. But when I looked at this roll, I had not one but two of my best images ever of New York City. What a coup!"

Magnum Contact Sheets edited by Kristen Lubben is published by Thames & Hudson, external.