Migrant crisis: Memorable pictures by BBC correspondents

- Published

BBC correspondents and film crews are out covering the huge movement of migrants across Europe and some are shooting still pictures as they go. We asked them to send in a memorable picture they had taken, along with a brief back story.

Lyse Doucet

We came across three young men from Aleppo, Syria, waiting on this bridge in northern Greece. They were hoping against hope their fourth family member, 23-year-old Walid was still alive.

His brother Ahmed, head in hands, later asked me to take his picture just in case Walid would see it.

Five days later, Walid's body was found sheltered by a tree at the river's edge. He had tried to swim across the river ahead of the others, not knowing there was a bridge to cross. They paid a terrible price in their journey to Europe, but said it was part of their God-given destiny.

Bethany Bell

I saw this artificial leg, lying at the side of an Austrian lorry park at Nickelsdorf, right on the Hungarian border. It's the first place that migrants reach once they enter Austria.

Most of those who cross the border here do so on foot and are met by the Austrian authorities and the Red Cross, who provide food, medicine and clean clothes.

Many exchange their old, worn-out shoes for fresh ones, donated by Austrian charities. After a big influx of people, discarded shoes and clothes litter the tarmac. But a prosthetic leg is another matter.

Who did it belong to? Why was it needed? Was its owner given a new one by the authorities?

And where is he or she now?

Ben Brown

Exhausted and heavily pregnant, she had just reached the border between Croatia and Hungary at Beremend. She could walk no further. They brought a stretcher for her and wheeled her across no-man's-land.

I couldn't help wondering whether her baby would be born in Hungary, a new child of Europe. What would be his or her future? Would he or she one day listen to tales of the epic journey the migrants of 2015 had made, to build a new life for themselves and their children?

Guy De Launey

These people are walking across the fields close to the border crossing at Sid, leading from Serbia to Croatia. They were among the first refugees to cross using this route, following Hungary's closure of its border with Serbia the previous day.

Taxi drivers had simply dropped them off at the corner of a field and pointed them in the right direction, even though the official border was only a few hundred yards away. The mood among this small group was very upbeat - many of them were shouting "thank you, Serbia!" as they went.

You can see the young man shooting a selfie. Other people were making videos as they walked, short reports to update their families at home. I can't speak Arabic, but it was clear that they were saying: "Here we are in Serbia, about to cross into Croatia..." The relief was palpable.

Since then tens of thousands more have followed this route.

Anna Holligan

I took this photo just after sunrise at the Nickelsdorf border crossing in Austria. We'd been up all night speaking to people who had just arrived.

Mohammed broke down when recounting how their boat started sinking and he saw his children floating on the water. His kids were sitting on a blanket, tucking into bread and steaming bowls of soup, seemingly unaware that just a few days ago they'd come close to death.

A doctor from Aleppo told me the reason he left Syria was because he couldn't see any light at the end of the tunnel.

"After almost five years of civil war, the reason so many are leaving now is because they ran out of hope."

We were all shivering and tired, and then, as the sun rose over the transit camp, hundreds of people emerged from inside tents and under blankets and started a determined march towards the buses. For me this photo represents how so many of the refugees and migrants feel about Europe - this is a place that offers them hope for a brighter future.

Will Vernon

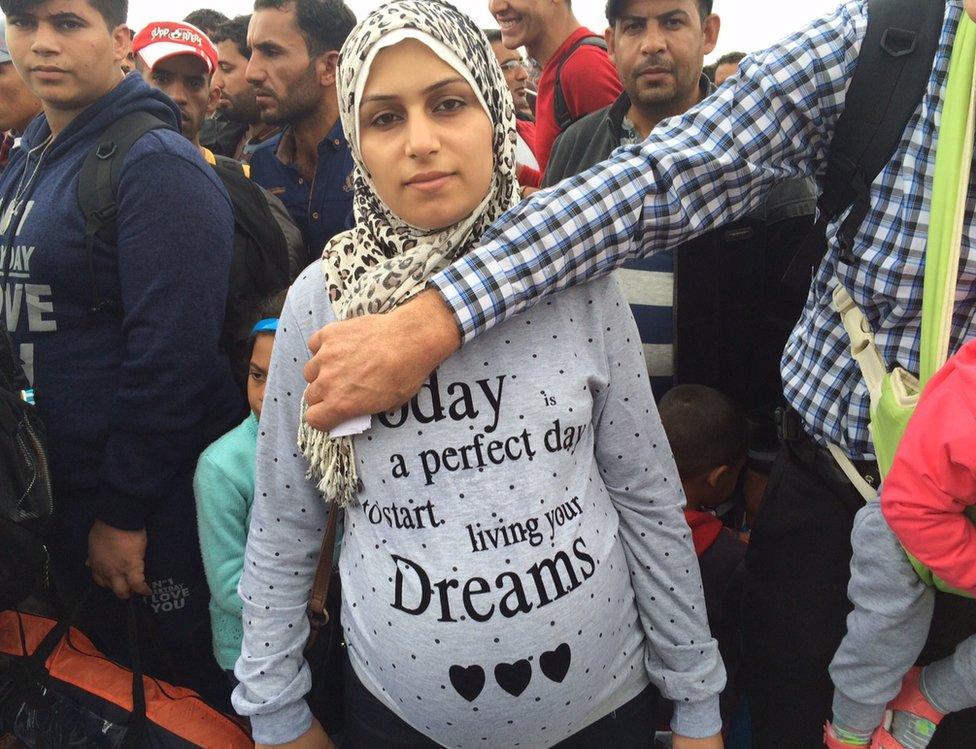

I took this photo of a young migrant woman, presumably Syrian. She stood out as her t-shirt was incredibly apt.

Initially she looked quite scared as I approached her, after my cameraman Bhas Solanki had spotted her.

She'd been queuing for hours and had finally reached the front of the queue of thousands of migrants at Mytilini port, on the Greek island of Lesbos. It is the main entry point for migrants arriving in the EU from Turkey.

She was fearful I was an official who would send her to the back of the line. I tried, via a Syrian man who spoke English, to explain how relevant her t-shirt is. We struggled with language problems, so in the end I just asked her husband to move her scarf so I could take a photo. I love her facial expression in this photo.

Gavin Lee

I saw Dara sitting in the middle of a road in the Croatian border town of Tovarnik. A bank manager from Damascus, he was one of 5,000 told to queue "two by two" in lines monitored by riot police.

Dara had sat for 12 hours with the other migrants, waiting patiently for the Hungary-bound buses. Struggling in the 36-degree heat, he'd placed tissue under the sides of his glasses because the skin above his ears was bleeding. His lips were blistered and sore with severe dehydration.

A kind man, despite his pain, he was reassuring others in the queue that things would be okay. I heard him telling them to keep calm and positive.

He'd been travelling on his own for a month to try and reach his sister in Germany, who was granted asylum there from Syria several years ago. A few days later I received the picture on the right from him. He made it to Bonn. Although he's sick with fever he can't believe he's reunited with his sister.

James Reynolds

On the Serbia-Macedonia border I stood on top of a hill with my colleagues Tony Brown and Tim Facey who took the photograph.

We looked down into the valley before us - and saw a line of hundreds of migrants and refugees slowly begin to snake up the long path. The youngest and strongest came first. Families with children followed.

Then, the line thinned out. At the back came the stragglers - the sick and the weak. Amongst them, we spotted a burly man called Azaat. He was carrying his elderly mother on his back - without pause, without complaint.

I've seen so many captivating moments during my time covering this story - but I shall never forget witnessing the man who refused to leave his mother behind.

Bruno Boelpaep

Lana is five years old and left her home in Damascus more than two years ago. She was waiting on the overcrowded platform of Gevgelija train station in Macedonia, near the Greek border.

More than a thousand migrants and asylum seekers were sitting in the blazing sun that day. There were only three trains a day - each with room for about 100 people, so three chances to get to the next stop, the Croatian border.

She had been there for nearly 24 hours with her mother and father and three-year-old brother Bilal, who was suffering from the heat. She was carelessly playing on the tracks, smiling to everyone around her and attracting a lot of smiles in return.

Matthew Price

This is a photo I took of a ship that had been specially chartered to take 1,700 migrants to Athens from the Greek island of Lesbos. As the evening wore on, during the hours of boarding, the windows slowly filled up with men, women and children.

All had arrived on the island in overladen rubber boats, across the water from Turkey, and all wanted to make it to western Europe - mostly Germany.

Beneath the ship were several tents, used by some of the thousands left in the port, waiting for another boat out. Yet it was the reaction to the photo which most sticks in the mind, after I posted it on social media.

"Spelt wrong" commented one person referring to the ship's name. "Should be Tera rist." (Punning on "terrorist.") The name "might suit the agenda of some of the passengers" wrote another. It shocked me - I hadn't even seen the words on the side of the vessel.

Ron Brown

A mum and her very young baby arriving at Croatia's transit camp at Opatovac, shortly after nightfall on Wednesday 23 September. Although hundreds were coming in by bus at this time - many of them families with young children - all was quiet, no doubt because they were exhausted from their journey so far.

Abdujalil Abdurasulov

As a video journalist I have filmed a lot of scenes of misery, when migrants and refugees were stuck on the border, or were rushing to board a train, pulling their crying children. At every location I felt people's sorrow of the past and fear of the uncertain future.

But when I visited a camp in Vienna where they are temporarily placed, I saw a man who was feeding his son and there was something captivating about them. They both happily posed in front of my camera. And then the father said: "My son is safe".

Nick Thorpe

I met Mourad (on the right, in the Las Vegas T-shirt), his brother, brother-in-law, and a Yazidi friend in the Harmanli refugee camp in eastern Bulgaria in early June. They had been there a month, after crossing the Bulgarian-Turkish border fence at their 7th attempt - a 13- or 14-hour walk through the mountains from the Turkish city of Edirne.

They are Kurds from Syria, travelling with their families, including three small children. The group includes an engineering student, a dentist, and an English teacher. They just want to complete their studies, they told me, in any country which will accept them.

Fergal Keane

For Noujain Mustaffa and her sister Nasreen the journey presented extreme challenges. Born with Cerebral Palsy she travelled nearly 4000 miles in her wheelchair. When I met her at Hungary's border with Serbia she was waiting with her sister and a family friend.

The Hungarians had sealed this part of the border. There was no way through. Thousands of migrants milled about, all wondering where they would go next. People were exhausted, angry, despondent. But not Noujain. She spoke of her dreams: how she wanted to be an astronaut and to meet the Queen, all in flawless English she'd learned from watching American soap operas. Noujain never stopped smiling. Her good humour and positivity touched us all.

"I won't let other people tell me who I can be," she said to me. This week Noujain arrived in Germany and claimed asylum as a refugee. Her first priority is to get advanced medical treatment - she hopes to be able to learn to walk.