In pictures: Roma slums in Romania and Slovakia

- Published

Roma family in Ocna Sibiului, Romania

More than 70% of Europe's Roma (Gypsies) live in dire poverty, often marginalised and victims of discrimination.

Europe is estimated to have 10-12 million Roma, many of them concentrated in eastern, former communist countries.

Back in 2005 the Decade of Roma Inclusion was launched - a global initiative by the EU, UN and World Bank to improve housing, jobs, health and education for the Roma.

The BBC's Delia Radu visited Roma in Romania and Slovakia to find out what, if anything, was achieved by that initiative.

The top picture shows Constantin Moldovan and his children on the outskirts of Ocna Sibiului, a town in Romania's central Transylvania region.

Desperately poor, they often skip meals and the family of 11 squeezes into a two-room, crumbling house.

The community lives under steep slopes prone to landslides - so locals call them "People of the Ravines".

"Of course we're scared whenever the earth comes down," said Mr Moldovan, as a hissing noise accompanied a minor shower of sand and clay.

"But what can we do? The local authorities aren't interested in giving us any help," he complained.

Across the road lives Petruta Paraschiva Otvos. When I visited 10 years ago she told me how she had been buried alive in a landslide in her backyard, then dug out by her neighbours and taken to hospital.

Since then she has done menial jobs in Spain, together with her four children, and they managed to build this new home, with four rooms for four families.

She is proud to have a two-storey house, but told me they often skipped meals, too, to save money. She often borrows money from neighbours to buy bread and medicines for her disabled husband, who lost a leg many years ago and has only a meagre pension.

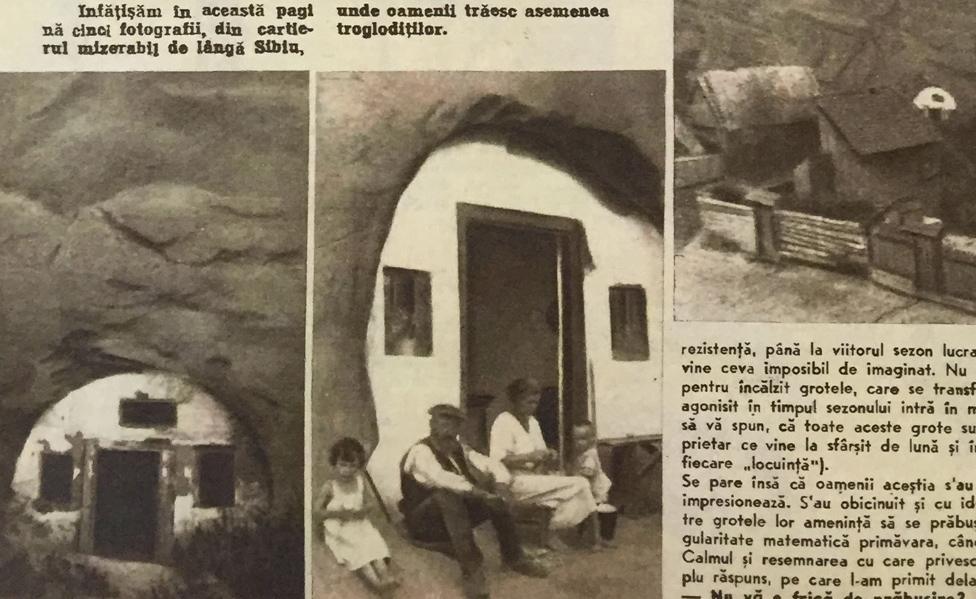

The poorest of the poor in Ocna Sibiului carve out a hole in the hillside and call it home: social housing from Mother Nature.

A Roma woman in her 40s lives in this cave dwelling. She works as a cleaner.

The local authorities say anyone who lives in a cave dwelling isn't a native of the town. They say the poor Roma get a lot of aid but waste it.

When I asked about the landslide danger, the authorities said they had provided plots of safer land elsewhere in the town.

But that begs a question: if the poorest Roma cannot afford decent food and clothing, how can they afford to build a new house from scratch?

The cave dwellings are not new: they were featured in a 1936 magazine article entitled "The poorest people in Romania".

The plight of the "troglodytes" back then was recorded by The Illustrated Reality.

Roma have had settled communities in Europe for centuries, but are often treated as outsiders. Their roots go back to India - their nomadic ancestors brought with them a language related to Sanskrit.

Some of Transylvania's Roma have prospered.

Ilie and Rodica Ciociu and their grandson live in Apoldu de Sus. They are among the minority of Roma who have stable jobs.

Ilie runs his own small business, having finished a business course. Ten years ago he was in the wool trade, constantly fearing that the police would seize his merchandise. But now he is in the Roma Party and a local councillor.

Rodica handles Roma health issues. But in the summer she picks strawberries in Germany, like some other Roma in the village who get seasonal work on German farms. That earns them enough to improve their homes - and sometimes they can live off their earnings for months.

Many other Roma in Apoldu de Sus live in ramshackle mud houses. Ilie Pasu's mud house collapsed and now he lives in a shipping container, to which he added a flimsy roof.

A report , externalon the Decade of Roma Inclusion acknowledged that poor housing remained a persistent problem in Roma communities.

Ilie Pasu shares this cramped container with five children and his pregnant wife. He is looking for work.

In a 2013 survey, external by the EU's Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 27% of Roma men complained of discrimination when looking for work, based on their ethnicity.

Ten years ago when I visited Apoldu de Sus I met Roma who said Romanian employers avoided them because of their Roma identity.

The bleak district of Ferentari is not far from the centre of Romania's capital Bucharest.

About half of Ferentari's residents are Roma. Most people call this street "the ghetto", though its real name is "Orchards Alley". It is the most deprived and arguably the most dangerous street in Bucharest.

The locals live in overcrowded flats, mostly in one room without any central heating or gas. The area is rife with drugs and in the park nearby there is a bin for needles. Rubbish uncollected for weeks litters the streets.

In Slovakia more than 5,000 Roma live crammed into a shanty town in Jarovnice, separated from their Slovak neighbours.

It is the largest Roma settlement in Slovakia, where Roma complain that ghettoisation is particularly deep-rooted.

Sometimes walls keep Roma out of ethnic Slovak neighbourhoods.

In Jarovnice's case, the dividing line is a polluted creek.

According to the UN children's agency Unicef, in Eastern Europe only 20% of Roma children are enrolled in primary school.

In 2005, many Roma children in Jarovnice skipped school, especially during the winter. The reason was very simple: they had no shoes.

A decade on, extreme poverty still keeps many Roma children away from school. Those who do attend do not mix with their Slovak peers. Most Slovak parents bus their children to a school outside the village.

That segregation prompted the EU to launch a discrimination case against Slovakia.

A rare success story in the The Decade of Roma Inclusion was the creation of a fund providing grants for Roma children. As a result, the number of Roma children who finish secondary school is growing.

Delia Radu's radio documentary was broadcast on BBC World Service.

- Published28 February 2014

- Published29 January 2013

- Published18 October 2012