Remembering the Kurdish uprising of 1991

- Published

After more than a month of intensive air attacks and a short land offensive by the US-led coalition against Saddam Hussein's Iraq, the Gulf War of 1991 drew to a close. The goal to liberate Kuwait following Iraq's invasion in August the previous year had been met, yet Saddam remained in power and turned his wrath on the Kurd and Shia communities.

Photographer Richard Wayman had worked with many of the Kurdish groups active in Iraq and Turkey during the 1980s and decided he needed to be there. Here, he recounts his time covering the uprising of 1991.

Two days after the liberation of Kuwait, the then US President, George Bush made a statement to the Iraqi population, external, "In my own view… the Iraqi people should put Saddam aside, and that would facilitate the resolution of all these problems that exist and certainly would facilitate the acceptance of Iraq back into the family of peace-loving nations."

Thus emboldened, in early March, the Shia in southern Iraq, and the Kurds in the north, made almost simultaneous uprisings against the regime.

At the height of the uprising, control of 14 of the country's 18 provinces had been wrestled from Saddam Hussein's forces and fighting even spread to within miles of the capital, Baghdad.

I was a freelance photojournalist and from my London base I tried to piece together the logistics of getting out to Iraqi Kurdistan as soon as possible.

In the days before internet communications and mobile phones, getting usable or correct information was time-consuming. Often what was "correct" one day was "wrong" several days later. It took a few days for information to filter through. The best way, I felt, was just to get a flight out to eastern Turkey and see how the land lay, which is what I did and so managed to reach the border with Iraq.

The Turkish army had closed the border and journalists waited in the border town of Cizre for a way across.

After several frustrating days trying to get across the border legally, I teamed up with a couple from German ZDF TV and we made for Silopi - even closer to the border. After befriending some Turkish border guards at a farmhouse on the border itself we negotiated "safe passage" to cross the River Khabur which marked the border at this point.

On the border between Turkey and Iraq, a Turkish frontier watchtower in the foreground and an Iraqi fort in the distance with the Khabur River inbetween. The image was taken with a long lens giving some compression of perspective.

Late one night we pushed our raft, made of truck tyre inner tubes, into the fast flowing and cold waters of the river. On the far bank, an Iraqi border fort stood on a ridge invitingly.

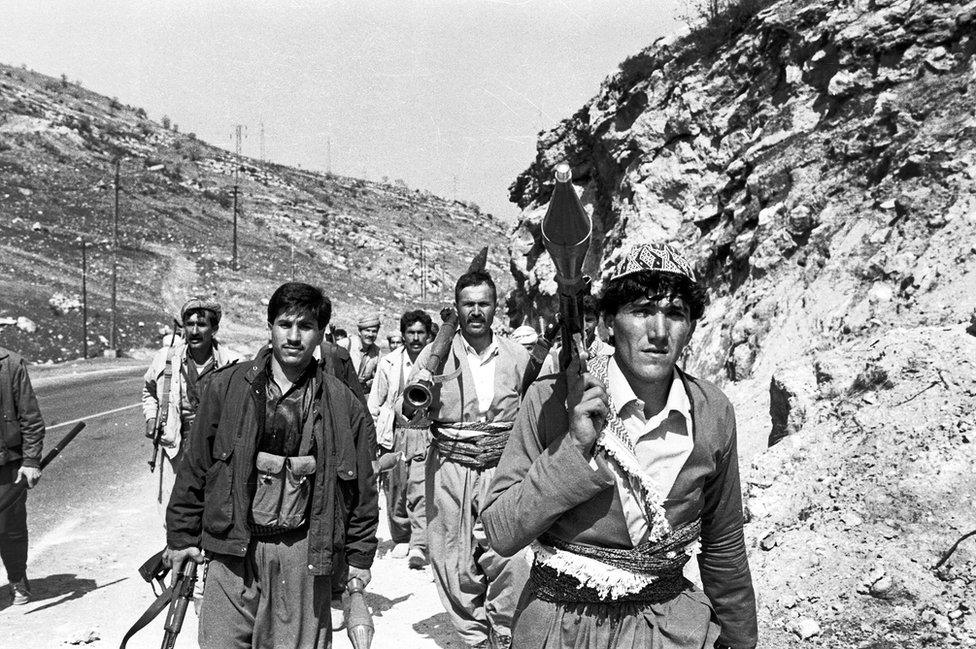

In the dawn light the following morning, a group of Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga walked us through a mined area to the safety of their fort.

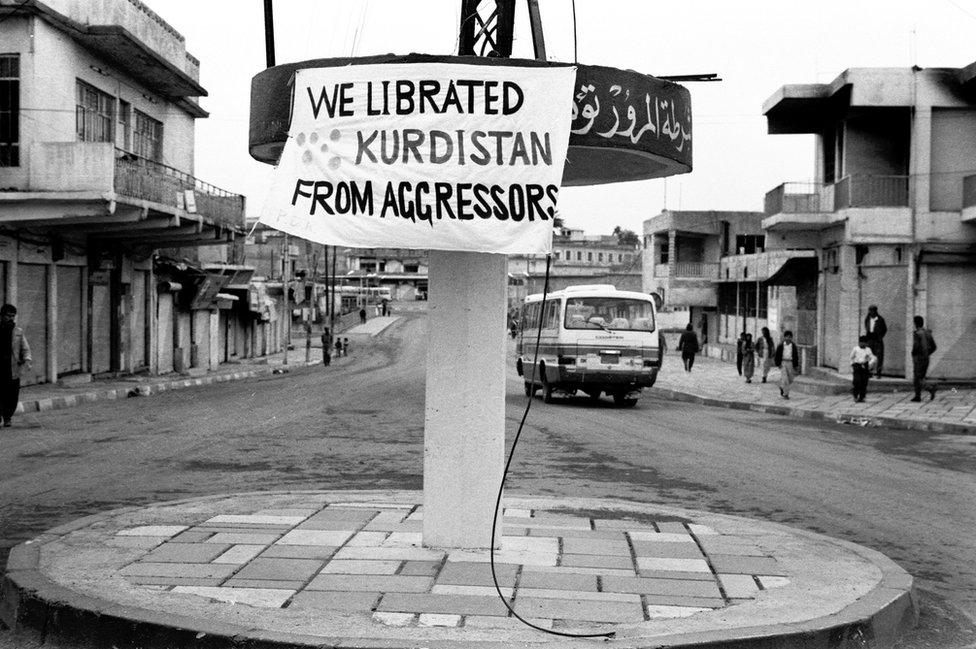

The Kurds were on a high - having recently taken the oil-rich city of Kirkuk from Saddam's forces.

Fighters from the Kurdistan Front with captured prisoners of the Iraqi army

But things began to change very rapidly for them as, within days, regime loyalists regrouped and went on an offensive to reclaim the cities.

They were helped by the fact that about half of tanks of the elite and politically reliable Republican Guard managed to escape from the Saddam-proclaimed "mother of all battles" in Kuwait.

In addition, the Gulf War ceasefire agreement prohibited the Iraqi military's use of fixed-wing aircraft over the country, but allowed them to fly helicopters because most bridges had been destroyed. The allied forces of the coalition had accepted the request of an Iraqi general to fly helicopters, including armed gunships, to transport government officials because of the destroyed transport infrastructure.

A fighter from the Kurdistan Front fires a heavy machine gun at an attacking Iraqi helicopter

Almost immediately, the Iraqis began using the helicopters to put down the uprisings. The outgunned rebels had few heavy weapons and few surface-to-air missiles, which made them almost defenceless against the gunships and artillery barrages.

Kurdish forces attempted to delay the advance of the Republican Guard to allow the evacuation of civilians from Iraqi Kurdistan to the safety of Turkey and Iranian frontiers but were inevitably crushed by superior fire-power of regime forces.

I fled with the refugees, walking to the border with Turkey on a two-day trek. The Kurds were terrified that Saddam's men would use chemical weapons against them - as they had done in 1988.

Kurdish people wait on the Iraq side of the Khabur River frontier with Turkey hoping to be allowed to cross to safety in Turkey. At this time the Turkish military would not allow any Kurdish refugees to cross.

Another Kurdish dream of freedom was thwarted. More than one million Kurdish refugees swamped the borders with Turkey and Iran. Many were to die in the mountains before the setting-up of safe havens by coalition forces on the Iraqi side of the border brought some respite for their plight.

Kurdish children and families carry their belongings towards mountains which mark the border with Turkey.

All photographs by Richard Wayman.