The women who served in Vietnam

- Published

Claire Brisebois Starnes enlisted in the Signal Corps of the US Army in 1963 as a skinny 17-year-old who was ordered to eat more bananas to increase her weight. Six years later she volunteered to travel halfway around the world for a tour of duty in Vietnam.

I met Starnes, along with Ruth Dewton and Jeanne Moran Gourley, both Vietnam vets, at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, known simply as The Wall. They are among more than 1,000 women, non-combatants, who served as line and staff officers and enlisted personnel in the US Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.

Vietnam Veterans Lt Col Ruth Dewton, Staff Sgt Claire Brisebois Starnes and Col Jeanne Gourley at the Vietnam War Memorial in the National Mall, Washington DC

Starnes, wearer of a Vietnam veterans' vest, has spent 17 years tracking down those women who served in non-nursing roles. Their stories are told in the book, Women Vietnam Veterans: Our Untold Stories, by Donna Lowery who served 26 years in the military, including 19 months in Vietnam. After half a century of silence, these forgotten women are remembered in this monumental anthology. It is long, heavy, etched with their names, but necessary. It is the women's Wall.

Starnes served as a translator before becoming a photojournalist and overseeing the publications section at Military Assistance Command Vietnam Office of Information (MACV Observer).

''I went there to see what was going on," says Starnes. "I had to go and look for myself. I saw it was not the military running the war, it was politicians running the war.''

Starnes carried an army-issued Nikon camera and her own Petri camera, shooting on both Kodak colour slide film and black and white.

Riding in helicopters to all parts of Vietnam, she soon learned to sit on her flak jacket to protect against the bullets and shrapnel that might hit the undercarriage.

Her photos are extreme: firefights in fields of mud and bodies, children at orphanages, tall buildings blasted apart, Bob Hope entertaining the troops and WACs at downtime, their hair in rollers.

''I had no idea how bad it would be. When I took the pictures, I never let myself feel anything," says Starnes.

"You had to tune out emotionally. It was only when I got home that I started to realise what I'd seen.''

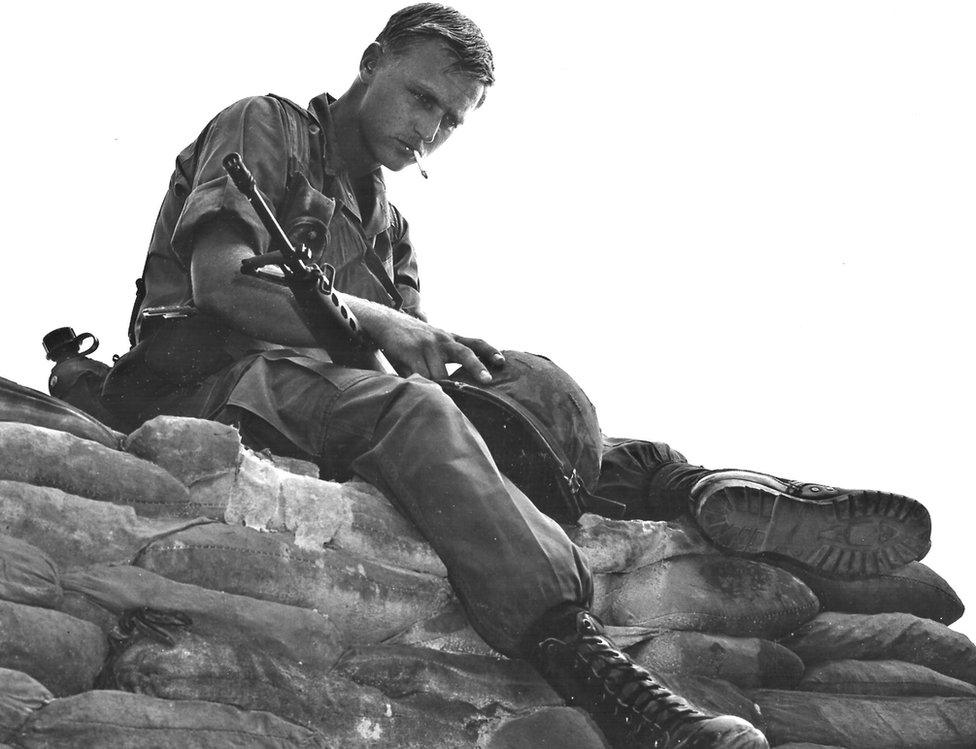

Soldiers of 1st Cavalry at Landing Zone Fiddler's Green, July 1969

An Australian medic tends to a wounded soldier 10 miles south of Soc Trang in the Mekong Delta, February 1970

A 25th Infantry soldier before a mission in the Tay Ninh Province, November 1969

The photo that sticks in her mind is a picture of a little girl playing inside a roll of barbed wire.

''She could have been ripped apart. She seemed so happy at that moment and yet there were craters around. Overall the kids were so resilient, or maybe they didn't understand the seriousness of it.''

By March 1973 and the withdrawal of US troops and the remaining WACs, an estimated four million people had died in the Vietnam War. For most returning veterans there was no welcome home. Being heckled and spat on at the airport was the beginning of their private aftermath.

Women especially learned to keep silent about being in 'Nam. Many just tried to get on with life, careers and families, burying their inward and outwards scars, shame or pride, horror or honour, all mixed up with memories of friendships forged and loves found. Many have died without daring to reveal they served in Vietnam. All believe it changed their lives, for better or worse, but certainly forever.

Starnes returned to the US after five tours, and is decorated with the Vietnam Service Medal with Silver Star, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal and Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross. She too tried to bury her memories in work, career and children, but eventually sought help in a group therapy session for Vietnam veterans.

Starnes comforts a visitor to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

She was the only female in the room and was verbally abused by male veterans. She tried to explain that in Vietnam there was no safe area, everybody who served was in combat, but they didn't want to hear. She left feeling ashamed and never again sought help.

In 1997, along with fellow veteran Precilla Landry Wilkewitz she attended the dedication of the Women in Military Service for America memorial (WIMSA). They each wore a blue vest with the dates of their service written on the back, in the hope of being spotted by other women who had served in Vietnam. One thing led to another and in 1999 they formed the non-profit Vietnam Women Veterans (VWV) Inc.

The Vietnam Women's Memorial stands a short distance south of The Wall

So began the long road tracking down others, the aim being to bring recognition for non-nursing women who served in Vietnam. That same year the group held its first Women Vietnam Veterans Conference in Olympia, Washington. For the first time, the women were recognised as Vietnam veterans and were officially told "thank you" and "welcome home".

''When I give my talks to help promote the book I begin with, 'Hi I'm Claire Brisebois Starnes and I'm a Vietnam War veteran'. I have only been able to say that since 1997. I didn't dare say it because no-one really understood. No-one cared, no-one was interested and it hurt too much.''

As I walk through the National Mall, away from the glare of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, people see Claire's vest and drift towards us. One woman, in tears, reaches out to her. Another asks, "Can I hug a vet?"

A male veteran selling leaflets for sustenance strokes his throat where shrapnel hit and tells her: ''When I came home they called me a baby killer.''