Colours in nature - and how we see them

- Published

A new exhibition exploring the relationship between colour and vision in the natural world is opening at the Natural History Museum.

Intense and vibrant natural colours will be displayed in specimens and photographs of insects, animals and plants. At the heart of the exhibition - Colour and Vision, external, which opens on 15 July - is the question of how we perceive colour.

"The message we hope people will take away from the exhibition is that colour and vision are inextricably interwoven in evolution," says researcher Greg Edgecombe.

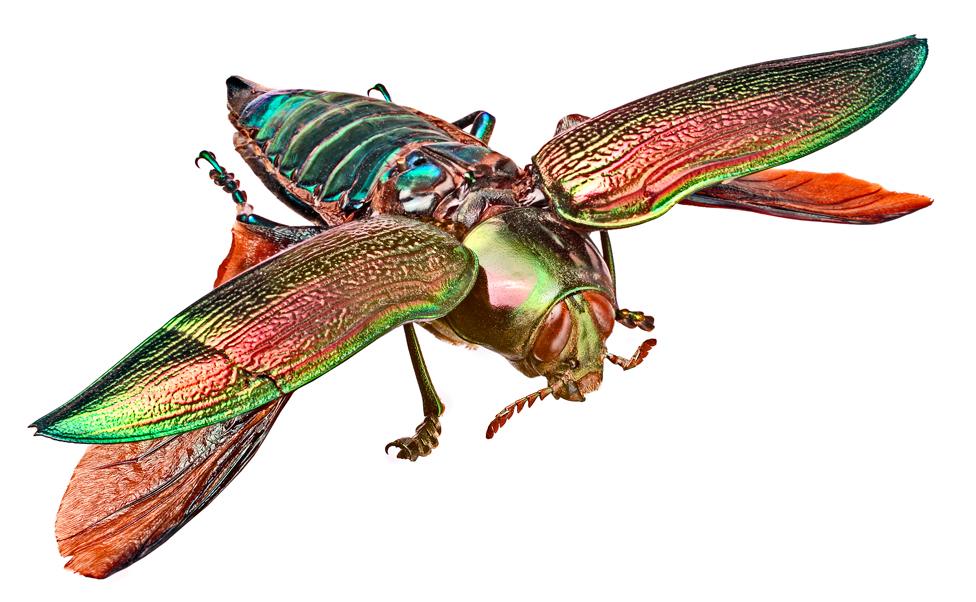

The vibrant hues found on the wings and feathers of some birds and insects can be explained by two different types of colour, says Mr Edgecombe - structural colour and pigment.

Iridescent feathers - such as those of the hummingbird - are due to structural colour

Structural colour

"Structural colour is produced by light interacting with microscopic structures on surfaces," he says.

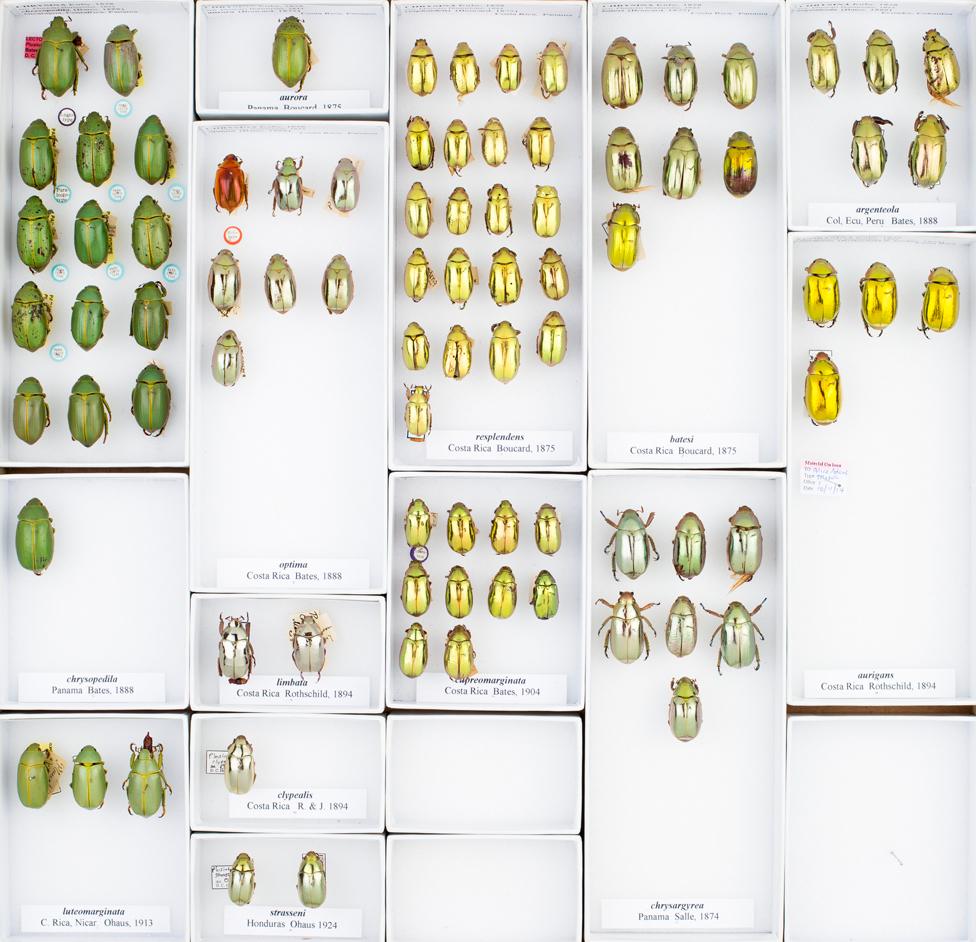

"This sort of colour is on some bird feathers and [the] metallic surface of beetles. "

Exhibits, such as the beetles below, have retained their colour even after decades of preservation, because structural colour lasts much longer than pigment.

Pigment

Pigments, found in hair and skin colour, are a group of different compounds that absorb light, says Edgecombe.

"Different pigments absorb different wavelengths of light and reflect other wavelengths - this affects what colour we are seeing," he says.

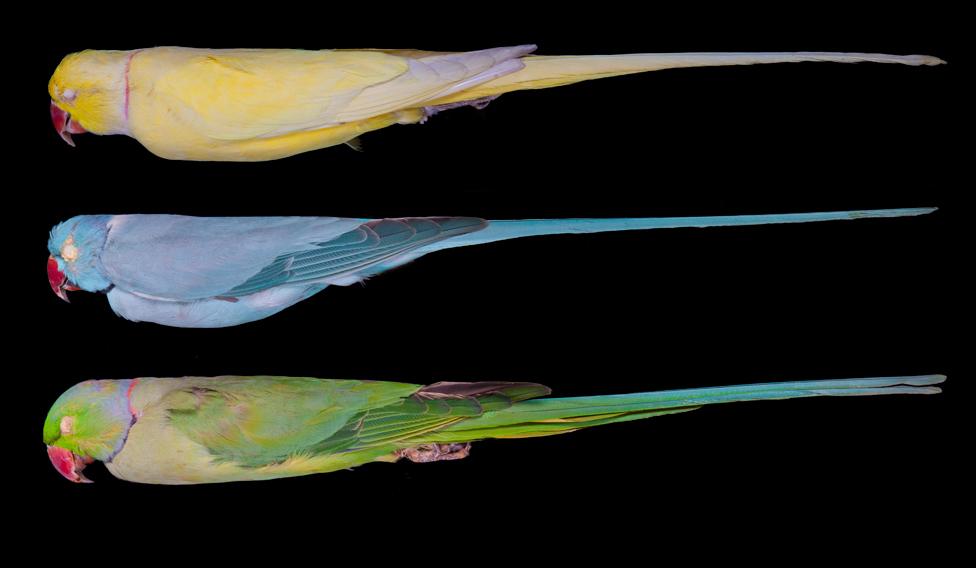

Sometimes colour is created by the combination of pigment and structural colour.

These rose-ringed parakeets above are an example of how structural colour can combine with pigment to create another colour, says exhibition developer Fiona Cole-Hamilton.

"Blue is really rare as a pure pigment in animals and is in this case caused by structural colour," says Ms Cole-Hamilton.

"When there is also a yellow pigment present [as in the parakeet pictured above, at the bottom], the animal would appear green."

The exhibition also examines the purpose of colour in nature, exploring the way in which animals see potential mates, prey and predators.

Vibrant colours might stand out in the wild, but they can also be a warning to potential predators.

"Bright colours can mean the animal is saying, 'Don't eat me,'" says Mr Edgecombe.

The eyes have it

An important theme in the exhibition is what animals - including humans - experience when they see the "same" colour, says researcher Suzanne Williams.

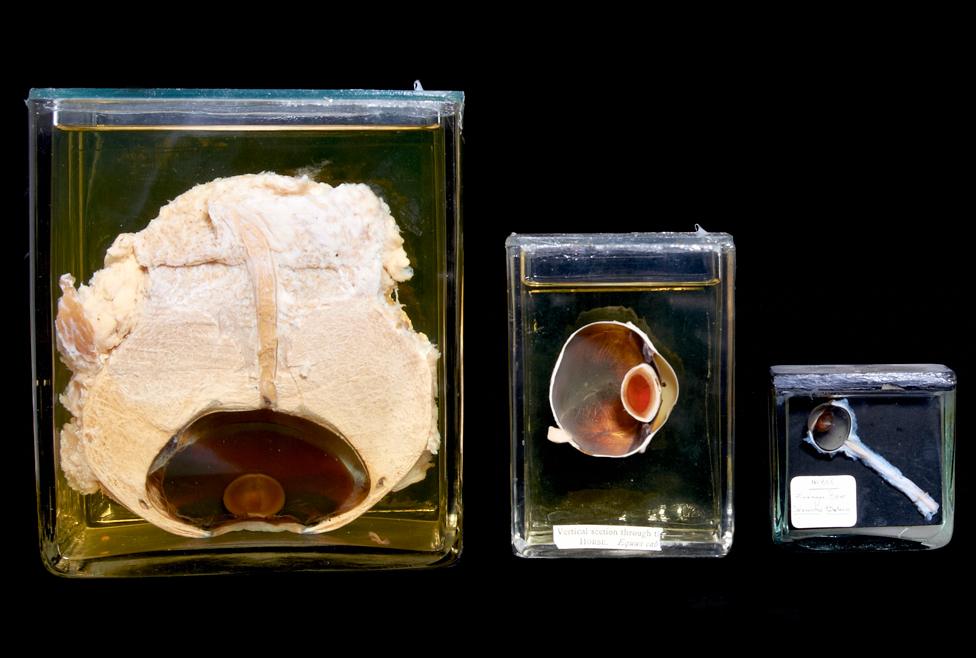

Cross-sections of 112 preserved eyes from the vertebrate kingdom help to show the way each creature processes colour differently.

"There is no such thing as colour without eyes to perceive it," says Ms Williams.

"You require eyes that are capable of differentiating between light of different wavelengths and a brain that can process the data in order to perceive colour."

The specimens form a "wall of eyes" in the exhibition, ranging from the eye of a black whale to that of an osprey.

Vertebrate eyes are all similar in their make-up. Each works as a "camera", letting in light through a single opening.

But there is a huge amount of diversity between different vertebrates' eyes, says Ms Cole-Hamilton.

The black whale, for example, (eye pictured below, left) "swims at such depth that the eye has to have a large aperture to let as much light as possible in".

It is an indication of how animals have evolved to adapt to their environment, Ms Cole-Hamilton says.

The eyes of the black whale (left), the horse, and the Himalayan bear

Multiple eyes

Evolution in eyes is explored beyond the vertebrate kingdom.

The chiton (pictured below) has eight interlocking plates, rather than a single shell.

Scattered over the shell are hundreds of camera eyes, with a mineral lens.

"These eyes are probably used to help them spot predators," says Ms Williams, "so they can clamp down on a rock and avoid being dislodged and eaten.

"They are really unusual in that they have mineral lenses made of aragonite - a type of calcium carbonate - instead of protein.

"The benefit of having eyes is balanced by the fact that the eyes create weak spots in the shell."

Many spiders see in colour, using highly visual displays to communicate with each other, says Mr Edgecombe.

And they perform dances to display colours to the maximum extent.

This jumping spider has eyes at the front to focus on - for example - a potential mate, while eyes at the side provide peripheral vision to watch for predators.

Some of the effects of eye structure are imagined in a virtual reality experience, seen through the eyes of a female mantis shrimp in a mating dance with a male of the species.

The mantis shrimp, says Ms Cole-Hamilton, has 16 visual pigments, compared with the three in human eyes, meaning they have an incredibly broad colour spectrum.

They are also capable of seeing polarised light.

And the immersive experience should allow users to see through the eyes of the mantis shrimp, "experiencing how they communicate with each other using flashes of polarised light".

All images provided courtesy of the Natural History Museum, and subject to copyright.

Colour and Vision is at the Natural History Museum, external from 15 July 2016.