One man's search for diamonds

- Published

During its 11-year-long civil war, Sierra Leone became famous for blood diamonds.

Rebel and government groups fought brutally over diamond-rich territory in the north of the country and funded themselves by selling the stones to international buyers.

Fourteen years after the conflict ended, diamond mining operations are still under way in the northern district of Kono.

A South African company, Koidu Holdings, runs a large mine that uses sophisticated machinery to blast through kimberlite and identify diamond-dense areas in the deep earth.

Nearby, artisanal miners line river banks, armed with sieves, spades and buckets.

One of these miners, Philo, has worked in Kono for the past 23 years, but was driven out during the conflict and lived in Guinea as a refugee.

When the war simmered down in December 2000, he returned home and started diamond mining again a year later.

Many artisanal miners will admit that they have not found a diamond in months and are desperately poor.

Yet in a country where there is 70% youth unemployment, mining at least provides some form of livelihood.

Most men mine in a team of three.

Philo works with two friends.

One of them dives to scoop a bucket of mud and grit from the riverbed, while another man holds him down so he does not drift with the tide.

The third collects the bucket and empties it into a mound.

Once there is enough, the sifting begins.

The three men swap roles regularly, to avoid getting too cold.

Philo complains of chills when he gets out of the water and sucks a packet of cheap rum to warm up, saying: "This work is tough and physically straining - if I had the qualifications or opportunity to do another job then I would at once."

The swampy area around the river has been dug out by artisanal miners, who are dotted all over, urgently scooping mud and sifting through it.

At last, after three hours of sifting, Philo is thrilled to have found a tiny diamond.

Some miners are able to invest in what is known as a "rocker".

They use a power hose to squirt water through a layer of mud piled on to fine mesh.

Once the mud is cleared they are more likely to spot a glinting diamond.

However, Philo does not have this luxury.

"We are not able to afford this kind of machinery, we have to manage with just a bucket, spade and shaker [sieve]," he says.

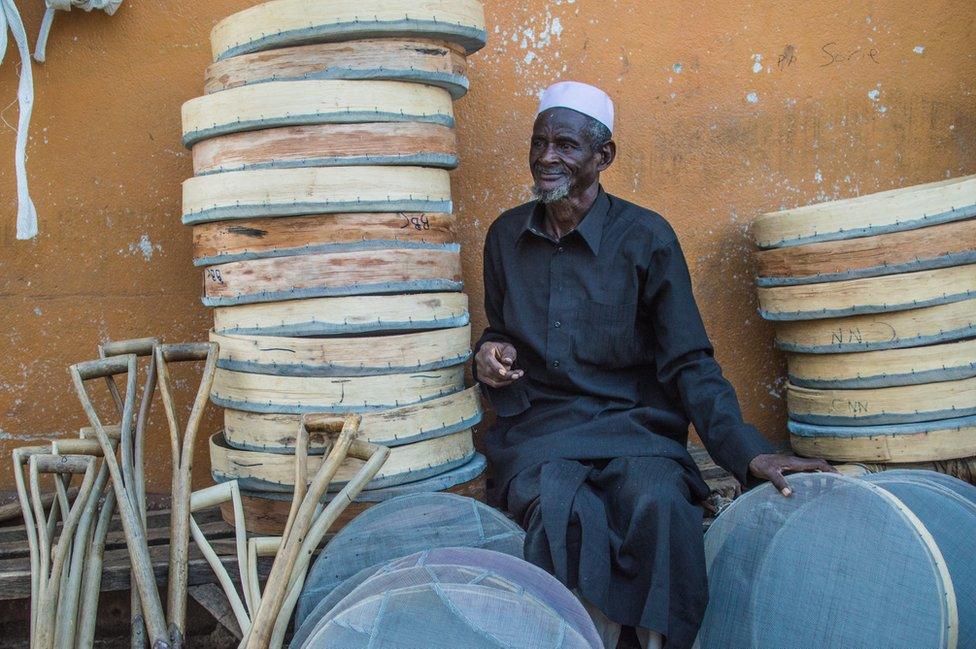

In the local market each shaker sells for 25,000 Leones (about £3.50).

Soon after Philo has discovered a diamond, he packs up early and heads into town with his team.

He is happy, saying: "This was a very good day, we hadn't seen a diamond for nearly a month."

On the way to his house, he bumps into his elder brother outside a shop.

They greet each other in front of the rocky kimberlite mountain that has been created by Koidu Holdings' blasts.

Philo says that he is jealous of their machinery and wealth, especially as diamonds in shallow ground are running out.

Back home, Philo relaxes in his room with his uncle.

During the conflict his mother was shot and killed by rebels, just outside the room in which he is now sitting.

His whole house was burned down and had to be rebuilt.

The following day Philo heads into Koidu town to sell his diamond in an office just off the high street.

The going rate is $3,200 (£2,520) for a carat that is 40% pure, and much less for gems of lower purity.

Philo obtains only $35 (about £28) for his find, but he is pleased as it is more than he had expected.

All photographs by Olivia Acland , external

- Published27 November 2023