Life after death? Resurrecting a modern ruin

- Published

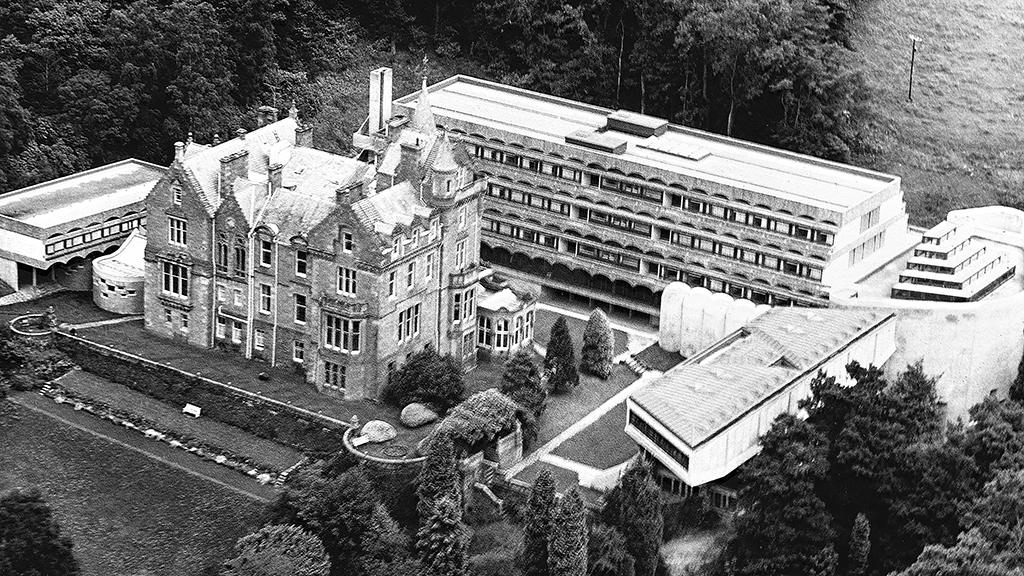

About 20 miles west of Glasgow lies a modern ruin. St Peter's Seminary was built only 50 years ago, yet by the 1990s it was derelict. However, plans to breathe new life into the building are now close to being realised.

The concrete ghost is hidden in woods on the north side of the River Clyde - the shell of an ambitious 1960s modernist building which the Catholic Church had planned to use to train 100 novice priests.

But the seminary - at the back of a golf course on the edge of the village of Cardross - was built in changing times. The Church would soon shift away from training priests in seclusion, instead placing them in the community.

The inauguration ceremony was held on St Andrew's Day 1966.

At the ceremony, the Archbishop of Glasgow James Scanlan commented on the "unique edifice… of such architectural distinction as to merit the highest praise from the most qualified judges".

But by the 2000s, the same space would be in ruins.

The post-war years saw the break-up of many of the traditionally Catholic areas in Glasgow - as sections of the old inner city were demolished and people moved into new high-rise homes or out to new towns like East Kilbride or Cumbernauld.

In this photo taken in the mid-60s, newly-built 20-storey flats in the Gorbals area of Glasgow overlook St Francis Church and Friary.

The Catholic Church embarked on an ambitious building project to serve these new communities - using architects Gillespie, Kidd and Coia (GKC).

GKC was also asked to build a new St Peter's Seminary near Cardross - to replace the old St Peter's College in Bearsden, which was destroyed by fire in the 1940s.

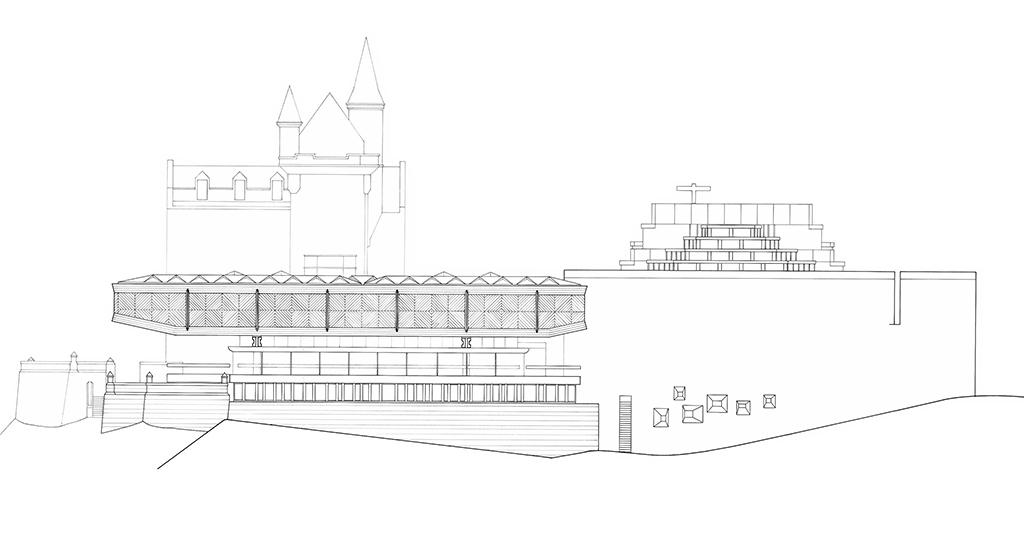

The architectural drawing above, of the new St Peter's south elevation, includes Kilmahew House - the 19th Century mansion which had been used as a temporary seminary since the late 1940s.

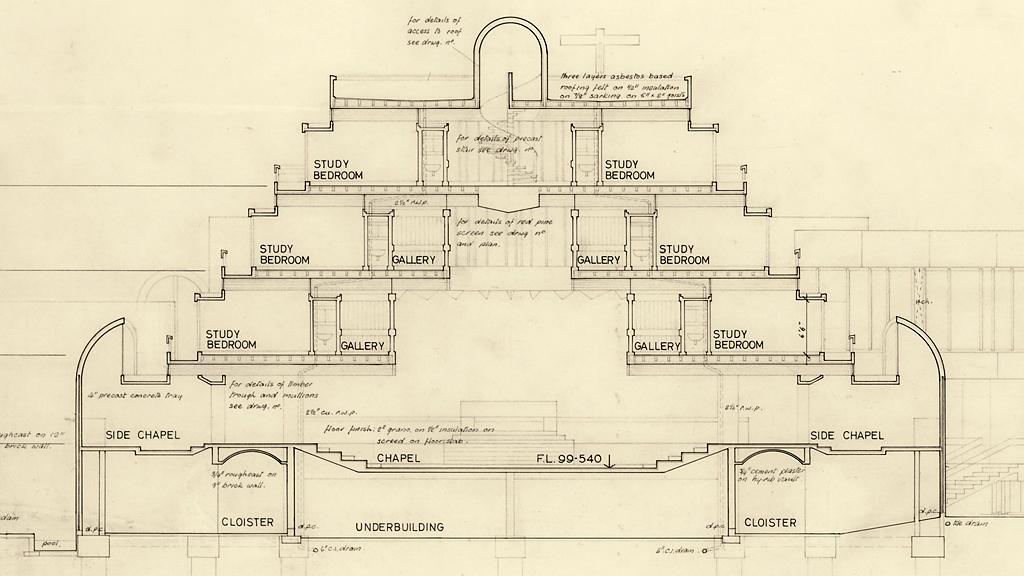

The trainee priests were to have "cells" in the main block - directly above the chapel - as shown in this section drawing from 1961.

The first sod on the site was cut in 1960.

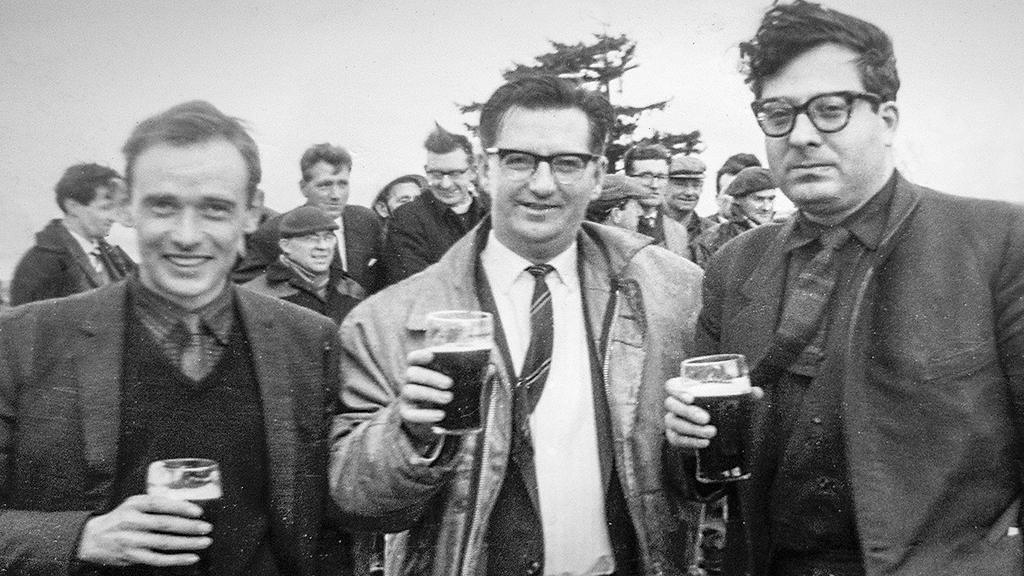

Architects John Cowell (left) and Isi Metzstein (right) - with project manager Stan Blair in the centre - celebrate here with pints of Guinness at the "topping out" ceremony in 1965.

Tucked away on a wooded hilltop, St Peter's was removed from the outside world.

The entrance to the main block was across a bridge spanning a shallow pool.

The architecture was celebrated at this early stage, and the project won a Royal Institute of British Architects Bronze Regional Award in 1967.

The granite altar in the sanctuary was the heart of the seminary complex.

Despite the sharp contrast between Kilmahew House and the St Peter's extension, the old mansion was an integral part of the college.

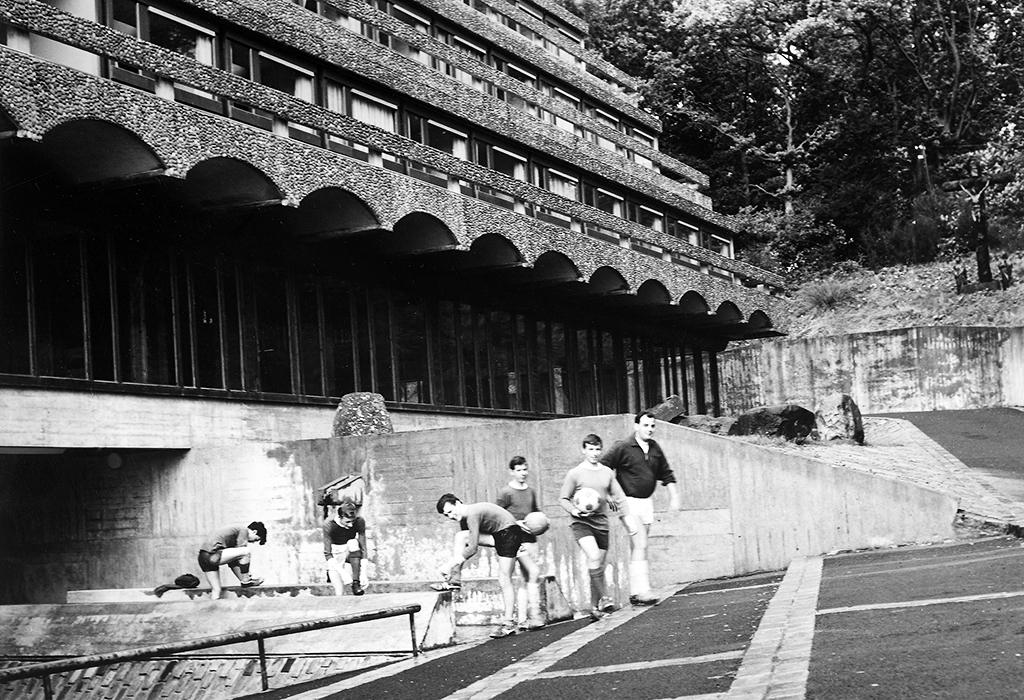

With the break up of traditional Catholic communities in the West of Scotland, and the increasing secularisation of society, St Peter's was never used to full capacity.

It was designed to hold 100 residents, but the highest number of students living there at any one time was 56.

This under population only exacerbated a series of maintenance problems on the site.

Inefficient heating, poor sound insulation and water leaks made life difficult for the trainee priests - but it did not stop them from enjoying a game of football.

In November 1979, only 13 years after it opened, the Archdiocese of Glasgow decided to close St Peter's because of the dwindling number of trainee priests, the maintenance issues and financial constraints.

The building was used as a drug rehabilitation centre for four years in the 1980s, but then fell into a state of disrepair.

Architectural interest remained though, and in 1992 Historic Scotland granted St Peter's Category A listed status.

Two years later, the adjoining Kilmahew House was gutted by fire and had to be demolished. Only the footprint of the mansion was left behind.

With no secure plans for the future, the site continued to deteriorate.

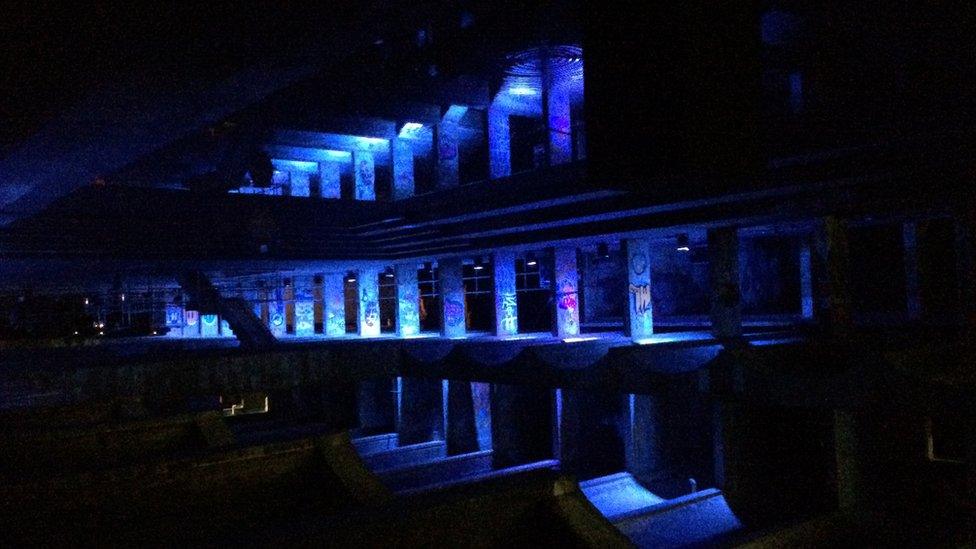

Protected by a high steel fence, nature started to reclaim St Peter's.

What the priests left behind, the graffiti artists claimed as their own.

Since the seminary's closure, numerous ideas have been submitted for repurposing St Peter's.

One ambitious plan - scuppered by the recession which followed the financial crash in 2008 - would have seen the modernist structure turned into a swimming pool and health spa.

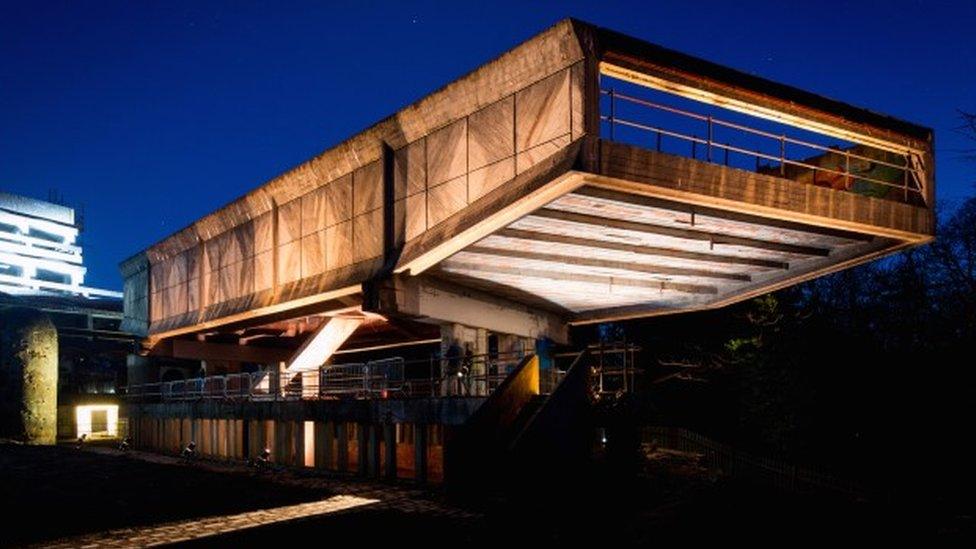

Now arts charity NVA is working towards turning the site into a dramatic space for public art, performance and debate.

The idea is to consolidate the ruin into a new design - with only partial restoration. A master plan was submitted in 2011.

With significant help from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Creative Scotland, NVA has reached its £7m funding target - and later this year work is expected to start on returning the site to a usable space.

A big clean-up last year removed lots of the detritus.

The sanctuary and altar area could be turned into a performance space like this.

But the public has already been given a chance to see the ruin of St Peter's in a new light.

In Spring 2016, NVA created a journey in light and sound through the concrete. Called Hinterland, the event was sold out.

St Peter's made a dramatic architectural statement when it was built, but its first incarnation as a seminary was short-lived.

It is hoped this 21st Century rebirth by NVA, bringing the structure back into productive use, will prove more enduring.

All images subject to copyright.

Historic Environment Scotland, in partnership with NVA and Glasgow School of Art, has published a more detailed history of the site - St Peter's, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal by Diane M Watters.

Satellite image from Google Maps

- Published23 March 2016

- Published18 March 2016

- Published16 January 2015