What everyday life is really like in Sweden

- Published

"We've got to keep our country safe. You look at what's happening in Germany, you look at what's happening last night in Sweden. Sweden, who would believe this?"

When US President Donald Trump launched this criticism of European refugee policy during a rally in Florida, Sweden was baffled. His implication was that something terrible had occurred in their country, in fact, it had been a normal February weekend.

As a form of cultural rebuttal, a group of leading Swedish photographers have collaborated on a project to show what life is really like for a typical Swede.

Taken over the course of the summer, the photographers explored topics ranging from the reality of life for asylum seekers to live-action role players in the country's forests.

Following a series of shootings and rock-throwing aimed at police, a group of women in the Stockholm suburbs of Fittja and Rinkeby became exasperated.

About 40 women, most of them immigrants, are volunteering on Fridays and Saturdays as "Night Walkers", to keep an eye on the neighbourhood's youth and help de-escalate conflict.

"If we see anything happening, we call the police," says Fatma Ipek and her companions. "We're strong, and we're never afraid."

As the contractions come faster, 26-year-old Mave Lochove gets a hand to cling on to from her mum Akiki.

It will still be nine hours of agony before a little girl will be born at Stockholm South General Hospital. She is called Juliana.

Juliana is the first to be born in this country to a family who fled from the Congo conflict, coming to Sweden in November 2016.

Since their home country doesn't have a lot of woodland, these scouts from Syria never had much of a chance to learn how to track at night, build bonfires or lash together a shelter. Instead, they've played music.

Since 2013, the Syrian Orthodox Scout Corps in Hallonbergen have carried on that tradition in their new country.

Improvising with wooden crates, Mia, Mery and Lea practise drumming in their school's changing room.

Mazen Bahe has developed his musical skills in the St Petrus' Band, which is getting ready to assemble for rehearsal as he warms up.

"Most of the players are beginners," explains leader Noel Tappo, who teaches almost 50 giggling children and youths up to the ages of 20.

"Our goal? Simply to help them to learn new things in life."

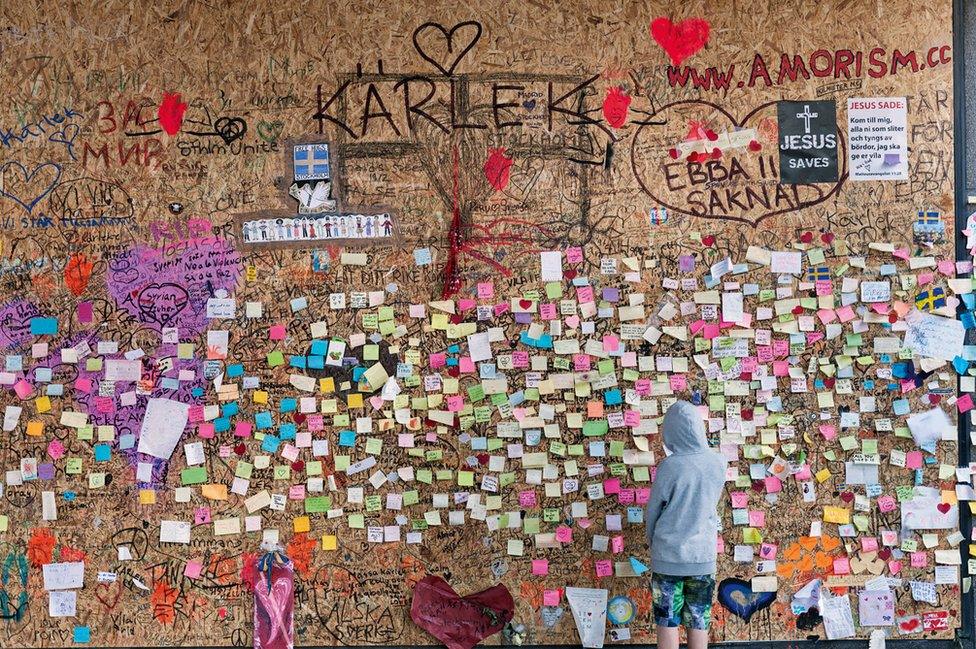

A young boy reads from the hundreds of notes posted on the spot where an attacker crashed a hijacked truck into the side of Ahlens department store in the capital.

The attack on 7 April claimed five lives. Rakhmat Akilov, a 39-year-old Uzbek national, has confessed to a "terrorist crime".

Even a traditional sport like tug-of-war can adopt modern materials and techniques: these men have discovered that a pair of roller skates rebuilt with a metal heel give the best grip.

There are no more than 200 participants of this sport in the whole country.

In a converted hospital in Fagersta, the semi-final of the Champions League is about to begin on the only TV.

Lina, Saleh and Bader are checking out Atletico Madrid's team line-up.

The children came from Afghanistan more than a year ago and are waiting in their temporary housing for a decision on whether or not they will be allowed to stay in the country.

When no one seemed interested in hiring a disabled former Algerian soldier, Antoni Khadraoui decided to open his own gym. Today he ranks among the world's elite in bodybuilding.

"When I'm on my back doing bench presses, I'm as good as anyone. But when I started out I wasn't allowed to compete because of my disability."

Antoni built his gym so that anyone can train, regardless of their physical status.

Thirty-seven year-old Maria Grancea is Romani and is doing her best to support her family by begging. She has left her two sons with their grandmother in Romania and is now in her seventh month of pregnancy.

"I beg because I want my kids to be able to go to school. I never got to," says Maria, who estimates her daily income is 100 Swedish krona (£9.50, $12.50).

Hall Prison, south-east of the city of Sodertalje, holds inmates convicted of the most serious crimes. Here, Asa Nensen works as a production manager for the laundry, ceramics workshop and plastic factory.

Prisoners who work in the facilities are paid 13 krona (£1.24, $1.60) per hour and are confined to their cells between 19:00 and 07:00.

An evening in Naimakka, an area at the top of Sweden that is one of the harshest places to live in the country. There's total darkness 24 hours a day in winter, and Naimakka holds the national record for lowest temperature of -48.9C (-56F).

Simon Siikavuopio has driven his snowmobile out on to the Koakama river, where in early May the ice is still 50cm (20 inches) thick.

A supper stew of moose, reindeer and cabbage is simmering in 80-year-old Ake's kitchen and four-month-old Balto, a Swedish Elkhound, joins the party.

Ake and Simon live a life that largely resembles that of their ancestors, close to nature and the changing of the seasons. It is 250km (155 miles) to the nearest town of Kiruna, which is the northernmost town in Sweden.

Birgitta and Bengt Bohlin, 87 and 86 respectively, met in 1955 when Bengt moved from Boras in the south-west to take a job building hydroelectric plants in Birgitta's native Lapland.

"It was instant passion," he recalls. "We found out right away that we had the same interests, the same simple demands of life."

While his owner is looking at an apartment, Sixten, a Jack Russell Terrier, investigates the Swedish housing market in his own way.

Finding an affordable flat in the capital gets tougher every year. Swedes pay a very high percentage of their income for rental housing.

As a result, Stockholm is an increasingly segregated city; demand for inner-city housing has driven apartment prices upwards and people of lesser means are relegated to the suburbs.

Orcs, elves and blackbloods take a break in a glade north of Vasteras.

For five days they live out their roles in an epic fantasy world, only breaking the illusion to use the toilet or call home.

Live action role-play games, Larps, have been popular among young adults in Sweden since the 1980s.

Last Night in Sweden is published on 12 September by Max Strom.