The black and Asian women who fought for a vote

- Published

UK women have been celebrating 100 years of the vote, looking back at the lives of those first suffragettes. But who were the black and Asian women who called for votes for women?

The 1866 petition calling for women to be given the vote on the same terms of men was signed by 1,499 women, from various walks of life. But, as far as we know, only one of those names belonged to a black or Asian woman.

Sarah Parker Remond was an African-American lecturer on anti-slavery and women's rights who had moved to London to try to get support for the abolition of slavery in the US.

Although the 1866 petition was unsuccessful, it did kick-start decades of organised campaigning by women calling for the vote.

There is, however, little evidence of black and minority ethnic women taking part.

Why is this?

Although black and Asian people had long settled in the UK, they made up a very small percentage of the population until after the end of World War Two.

At the time of the suffrage movement, it was mostly men that made up this community. Chinese, West Indian and African seamen had settled in London and other port cities - but female family members had tended not to travel with them.

Sarah Parker Remond

It may be that black and minority ethnic men and women did support the women's suffrage campaign, and that they have become "hidden from history".

One of the main reasons for this is the difficulty of establishing the ethnic origin of an individual from records.

Census records only documented a person's place of birth, but this is no guide to ethnic origin because so many white British men and women were born in Africa, India, or the West Indies.

Names yield few clues. Migrants from the Caribbean, for example, had acquired surnames that made them indistinguishable from white British men and women, for reasons associated with the unhappy history of the islands.

There are no suffrage campaigners that we know of with names that are obviously African or Chinese, and suffrage newspapers make no mention of women from China, Africa or the Caribbean taking part in suffrage activity.

Only women with Indian names stand out.

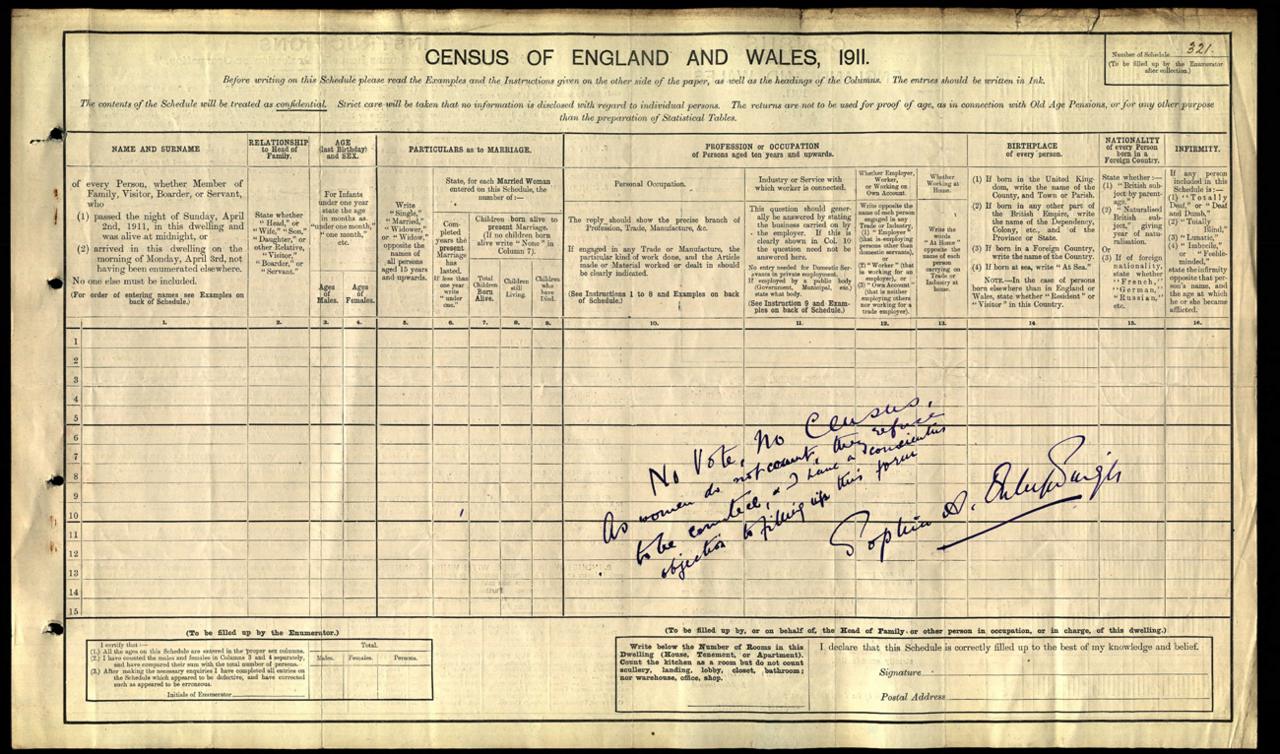

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh (pictured top), for one, played a relatively prominent part. The daughter of the last maharaja of the Sikh empire, she was also god-daughter to Queen Victoria, who had granted her a grace-and-favour residence, Faraday House, at Hampton Court.

By 1910 Sophia was an active member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), the militant organisation led by Emmeline Pankhurst. She spoke regularly at meetings of the Richmond, Surrey, branch of the WSPU and was a member of the Tax Resistance League, protesting against the exclusion of women from the franchise by refusing to pay taxes and rates.

In 1911 she had a diamond ring impounded against a fine for non-payment of licenses for a male servant, a carriage, and five dogs. In 1914 she was again fined for refusing to pay taxes - a pearl necklace and gold bangle were seized and auctioned at Twickenham Town Hall.

As writer Anita Anand reveals in her book Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary, the princess was involved in all aspects of WSPU activism, short of actual physical militancy.

In November 1910, on the day that came to be known in suffrage history as "Black Friday", she was a member of the WSPU deputation to the prime minister, and was involved in the brutal battle with police that ensued in Westminster Square.

In 1911 she followed the suffragette call to boycott the census, writing across her census form: "No Vote, No Census. As women do not count they refuse to be counted, & I have a conscientious objection to filling up this form".

She was willing not only to sell the WSPU newspaper, The Suffragette, to the passing public at Hampton Court but to be photographed doing so for the 18 April 1913 issue of the paper, alongside a newsstand poster that promised "Revolution".

After the 1918 law was passed that allowed women over the age of 30 who occupied a house (or were married to someone who did) to vote, Sophia maintained her interest in the advancement of women. In particular, she supported the enfranchisement and education of Indian women.

Sushama Sen was another Indian suffragette. In her book Memoirs of an Octogenarian she recalls taking part in a WSPU demonstration in 1910. At that time "there were few Indian women in London", she notes. She was invited to join in the march "led by Mrs Pankhurst to the Parliament House".

"It was a novel sight for a single Indian woman amidst the procession, and I was the subject of public gaze," she writes.

That gaze was surely attracted by the sight of a sari among the conventional Edwardian coats and dresses.

Certainly the following year, when putting out a call for Indian women to join a Coronation Procession in support of suffrage, the organisers of the Indian contingent promised the public the sight of "beautiful dresses".

The procession was staged five days before the coronation of King George V, with "Empire" as one of its main themes.

It was intended that contingents of women would represent Australia, Canada, South Africa, India, and the Crown Colonies and Protectorates.

However by the day before the organisers of the Indian contingent admitted "Though this contingent may not be as large as the other parts of the Imperial Contingent, it will be no less impressive".

It was certainly impressive enough to attract the attention of a photographer. But as we see from the resulting photograph, it would appear that only five or six Indian women took part in the procession.

Five women pose with a banner, behind which the sari of a sixth is visible. Perhaps that hidden figure is Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, who it was reported intended to take part in the procession. Two of the women hold elephant insignia, emblems of India. The remainder of those photographed appear to be white British.

One of the three original organisers of the India section was PL Roy (Lolita Roy), the wife of the director of public prosecutions in Calcutta.

Lolita Roy had come to London with her six children in 1901, apparently for the sake of their education, and lived in Hammersmith. She is one of those photographed and of the others, three are likely to be her daughters, Miravati, Hiravati and Leilavati, who had married Satya W Mukerjea Mukerjea in 1910.

The other woman on the left is thought to be Bhagwati Bhola Nauth, who was 29 years old and, according to her 1911 census, had already been married for 14 years.

At that time her husband was in India, where he was a doctor in the Indian Medical Service, her two sons were boarders at Rugby School, and she was living in a boarding house in Kensington. She had no occupation but was honorary secretary of the Indian Women's Educational Fund.

There is no evidence that any of these women played a further part in the British women's suffrage campaign, although they may well have done. Lolita Roy, Bhagwati Bhola Nauth and Sushama Sen were later involved in the campaign for the enfranchisement of Indian women.

Unfortunately, no photograph survives of the Crown Colonies and Protectorates contingent, which followed close behind "India" in the "Coronation Procession".

But it would seem likely that Britain's possessions in, for example, the West Indies and Africa, were represented by white British women who answered the call in the journal Votes for Women (9 June 1911) to carry small banners representing each colony.

A number of other women with Indian names appear in suffragette newspapers. A Miss Sorabji was involved with the Hackney branch of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) and in November 1912 Ramdulari Dube was one of the luminaries opening the WFL's "International Fair". She was a member of the league and was described as "showing the ability and charm of an Indian woman - and the picturesqueness of her dress".

A couple of ethnic minority men make an appearance in the history of the suffrage movement.

The UK's first ethnic minority MP, an Indian by the name of Dadabhai Naoroji, was a member of the council of a 19th Century radical suffrage society, the Women's Franchise League, and was wholly supportive of women's suffrage.

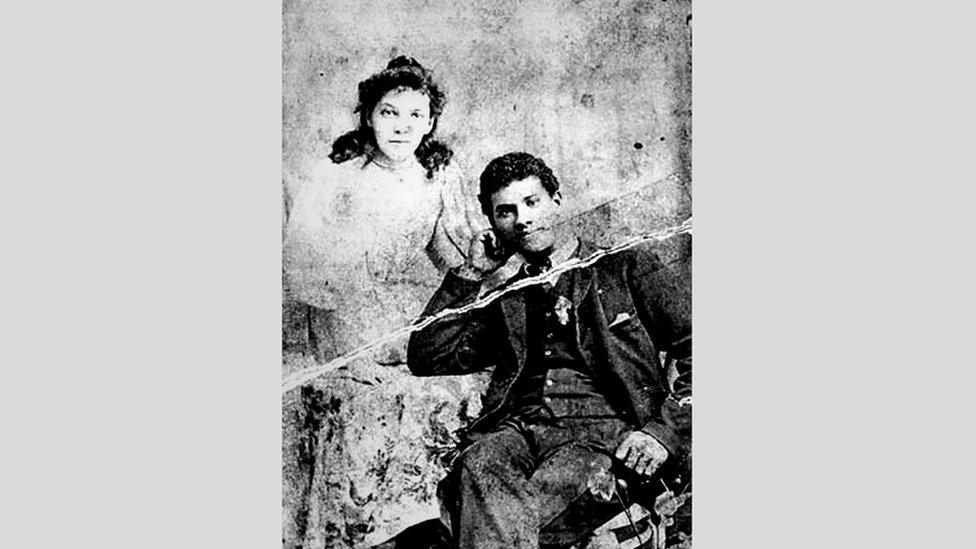

As for individuals of part Caribbean heritage who had a tenuous connection to the campaign, both were men and both were born in England to black sailor fathers and white British mothers.

One was Donald Adolphus Brown who was married to east London suffragette Adelaide Knight. He suffered a traumatic childhood after his father - a sailor in the Royal Navy, who was thought to have been born in British Guiana - murdered his mother.

Donald took his wife's surname and was widely known as Donald Knight. In Courage - a memoir of their lives - their daughter, veteran Communist party member Winifred (Win) Langton, wrote that Donald "vigorously supported his wife in every possible direction".

When Adelaide went to prison in 1906 after taking part in a WSPU demonstration outside politician Herbert Asquith's house, he made it clear that in her absence, he was happy to run the household and care for the children.

In a letter from Holloway, Adelaide wrote to Donald, "I have no other notion of slavery, but being bowed down by a law to which I do not consent. Women and negroes still have to fight for dignity and equality". In another letter, she wrote: "Your courage gives me heart to bear everything".

Adelaide soon left the WSPU, which she believed had little interest in working class women and, with Donald, joined the Adult Suffrage Society.

Apart from the photographs of the "Coronation Procession" and of Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, there is no visual evidence of the presence of BAME women at any suffrage event, either as protagonists or as onlookers.

However, it is to be hoped that in this centenary year, as the spotlight is shone more intensely on local histories of the suffrage campaign, something more of the involvement of BAME women and men will be revealed.

All images subject to copyright