The 100-year-old protest posters that show women's outrage

- Published

Recently rediscovered 100-year-old posters showing the struggle for votes for women are going on show for the first time. They pull no punches in their depiction of the strength of feeling among the women who fought for equal rights.

Addressed simply to "the Librarian", a bundle wrapped in plain brown paper was delivered to Cambridge University Library sometime around 1910, and it took over 100 years for the contents of the parcel to be rediscovered, in 2016, preserved in their original wrapping.

Underneath the faded paper was one of the largest surviving collections of suffrage posters from the early 20th Century.

They had been sent by a leading figure of the suffrage movement, Marion Phillips, who became Labour MP for Sunderland in 1929.

It is unclear why Phillips sent the posters.

"They were created to be plastered on walls, torn down by weather or political opponents," says Chris Burgess, exhibitions officer at the library. "So it is highly unusual for this material to be safely stored."

gThe posters going on show, external to mark the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which gave the vote to women over the age of 30.

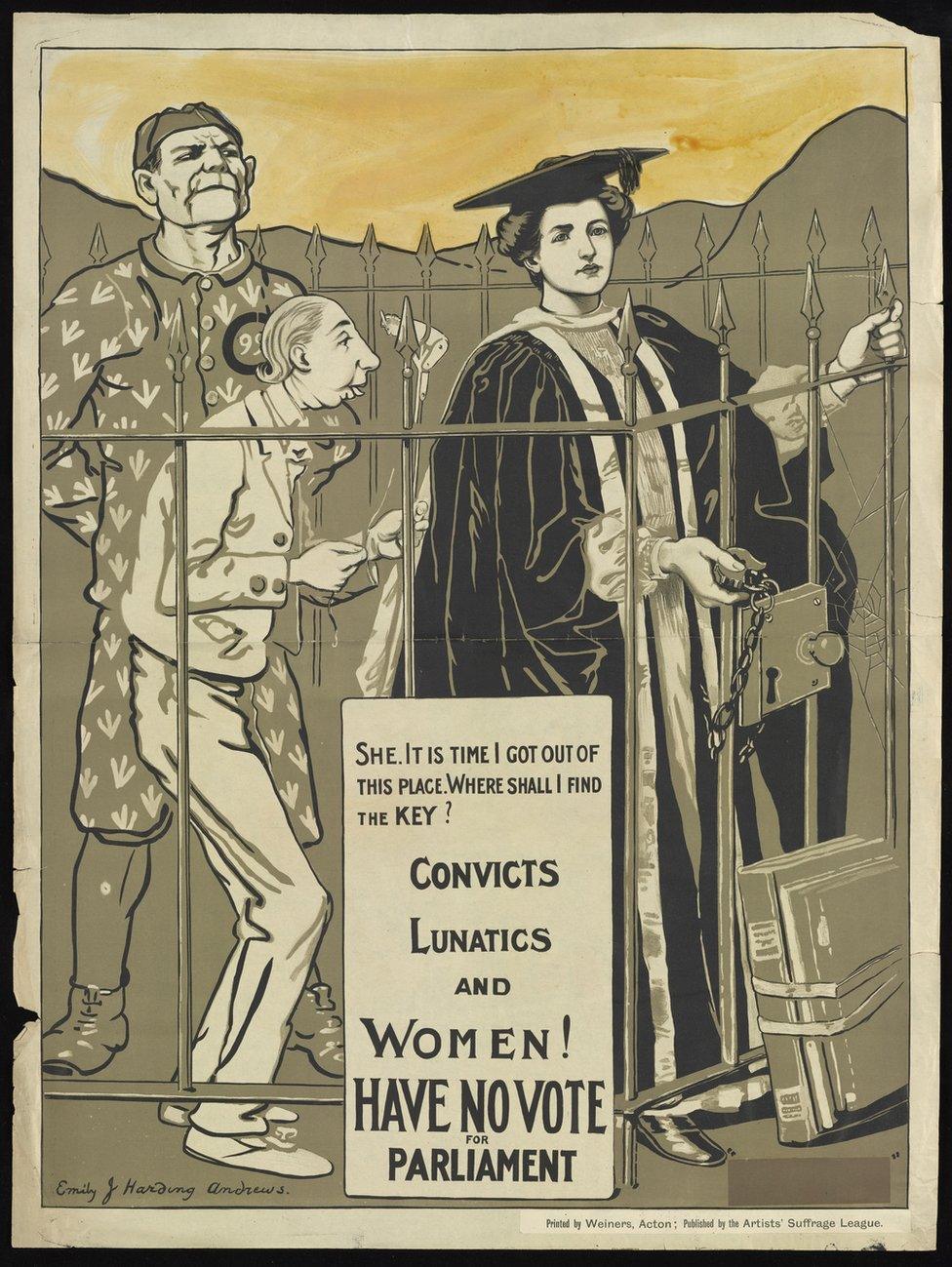

Because of Cambridge's prestigious university, local suffrage posters often featured women in academic dress.

Artists observed that the city's educated women were still grouped - in the eyes of the law - with the likes of convicts and lunatics.

Although Cambridge's women-only colleges such as Girton and Newnham had very active suffrage societies, the university itself was far from progressive.

By the end of the 19th Century, women were allowed to study at the university but were not given full degrees at the end of their studies. When an 1897 vote proposed to change this, there was outrage.

An effigy of a lady cyclist - a symbol of the new woman - was torn down and destroyed to the delight of the jeering crowds of male students.

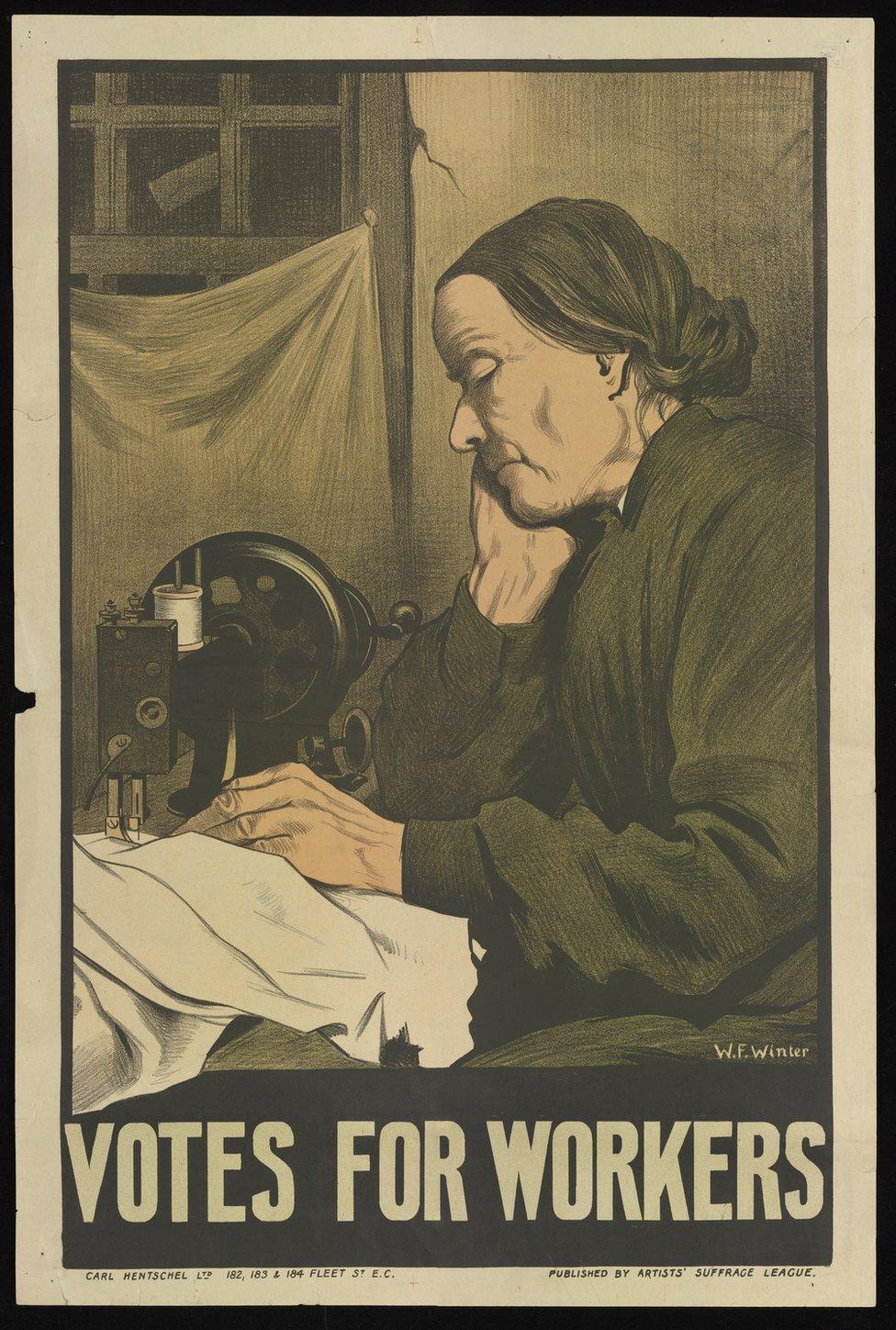

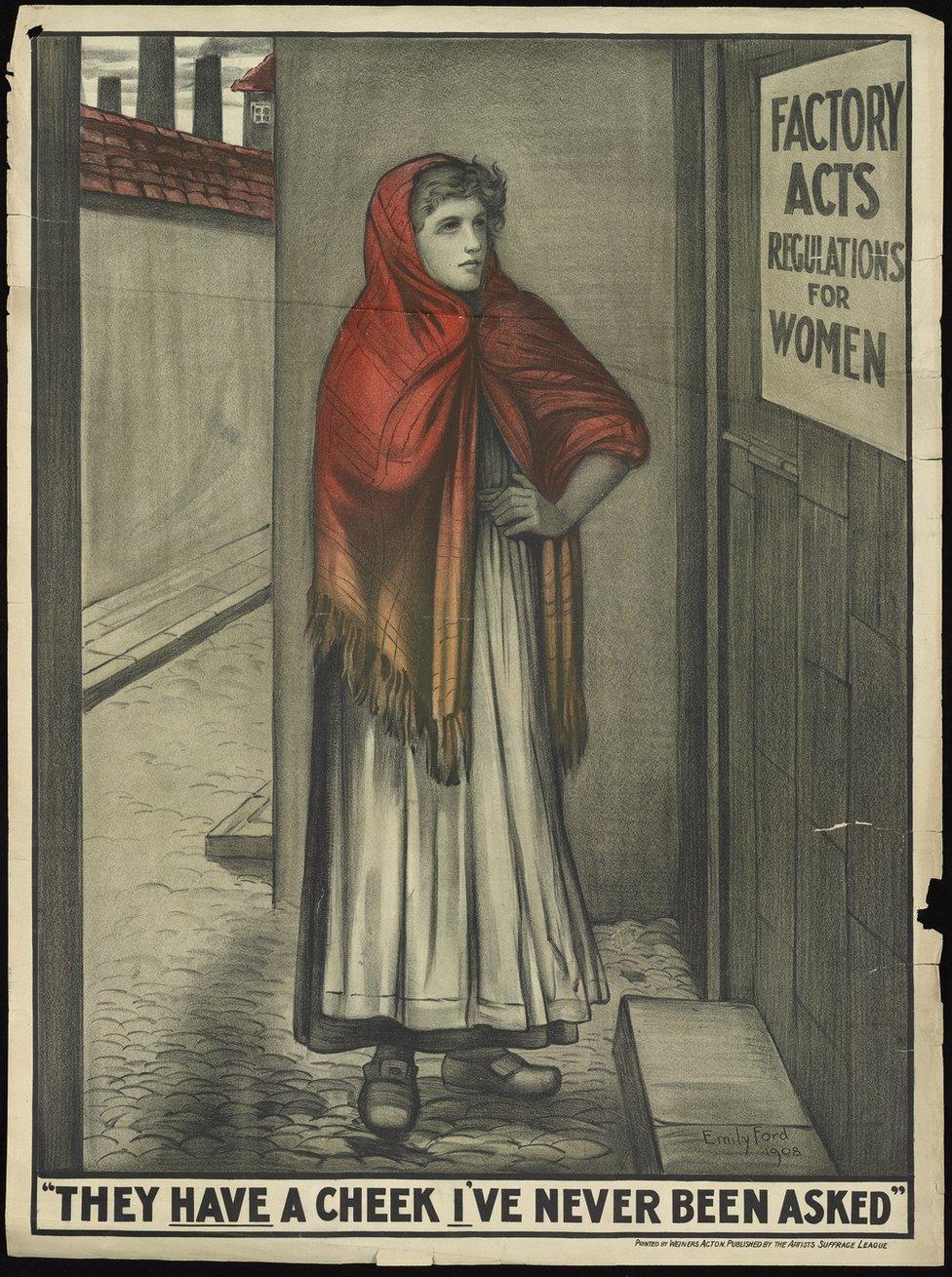

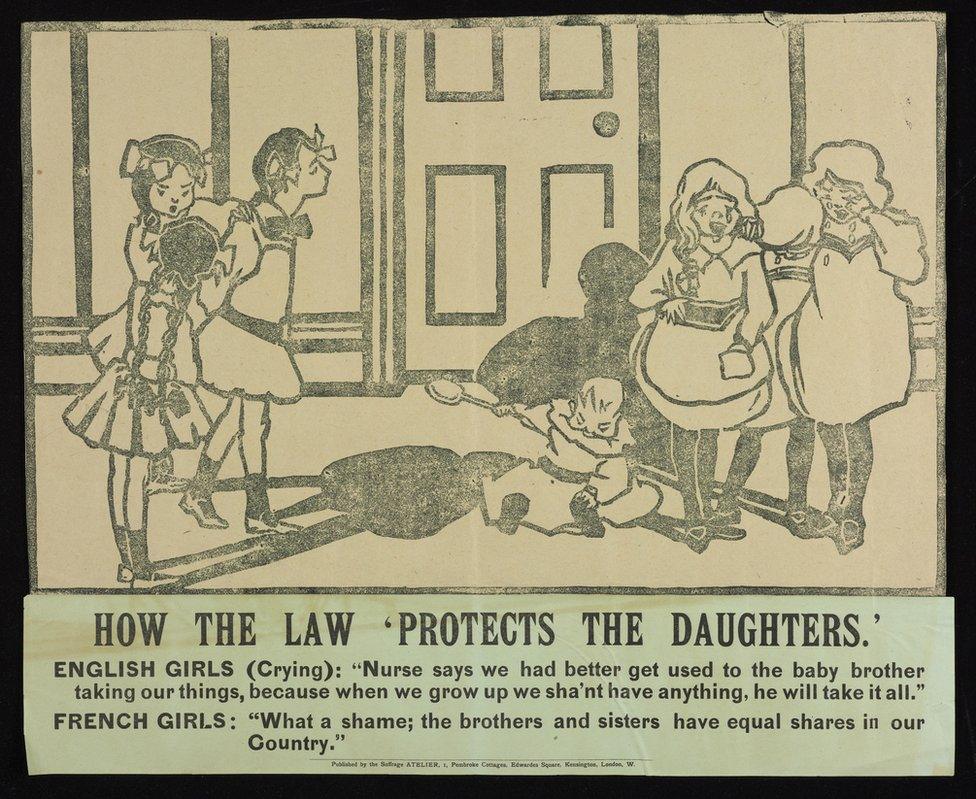

Posters also tried to appeal to working-class women, such as those working in textile factories or at home as seamstresses.

Some pointed out that these women were not even able to vote on laws that concerned women's regulations and rights.

This meant men were voting on what they believed to be best for women.

Lucy Delap, a historian specialising in this period, says most people in the UK were against women getting the vote.

As a result, "the suffrage movement definitely had to reach out to many women".

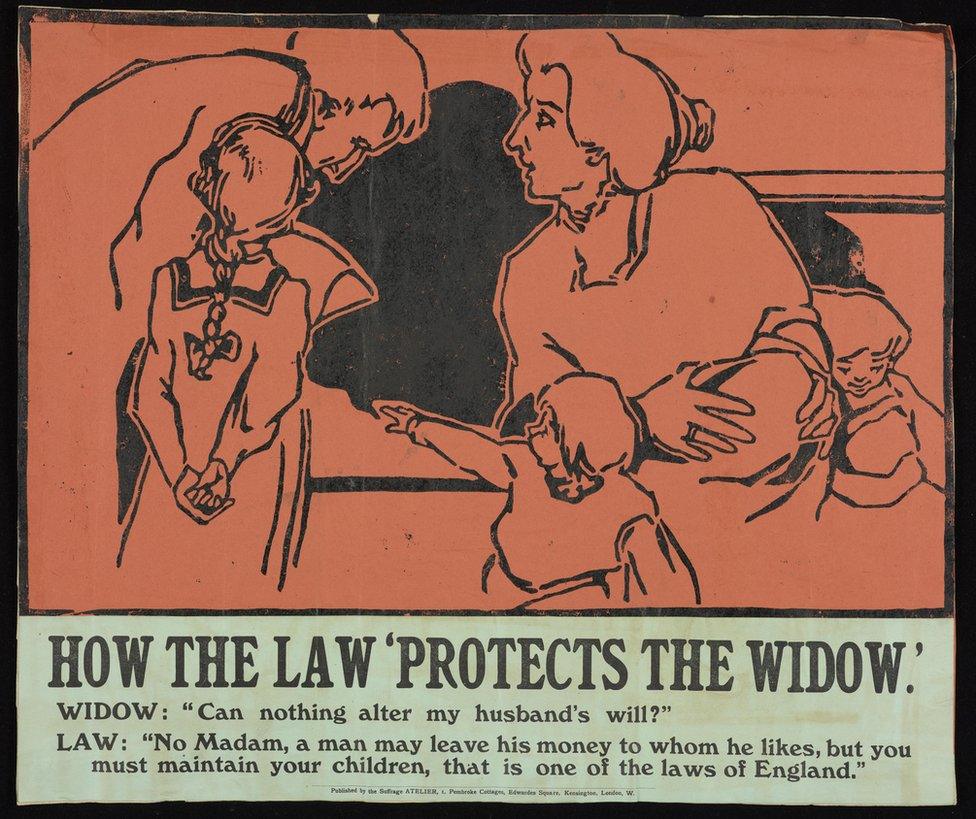

"Campaigning went far beyond the simple equality message - to point out how the vote could make a difference in households, at work, on the streets - matters that concerned all women," she says.

Print production was central to the suffrage campaigns.

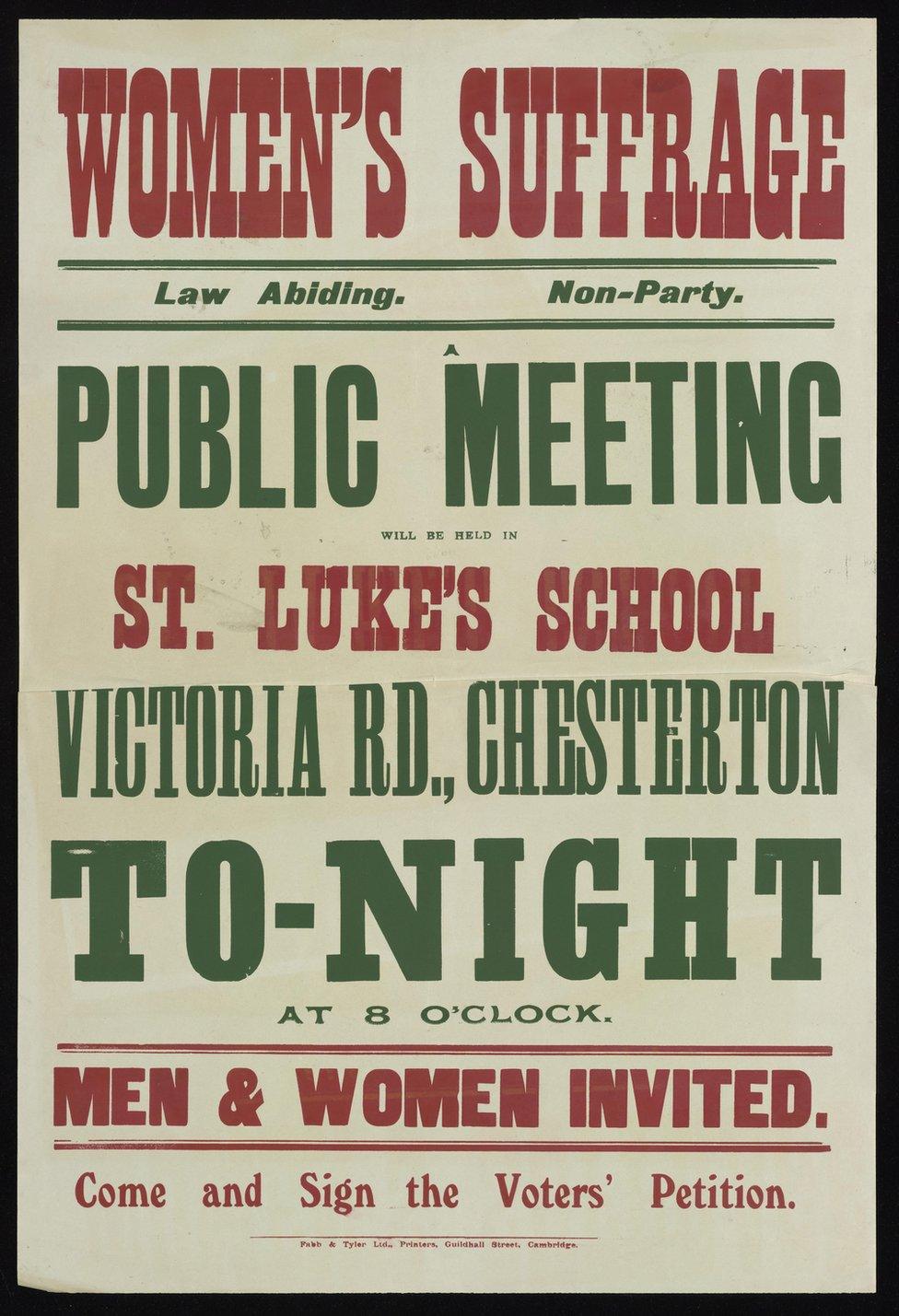

"People would be cranking out handbills to be distributed the same day through networks of sash-wearing volunteers, or printing posters advertising meetings taking place that same evening," says Delap.

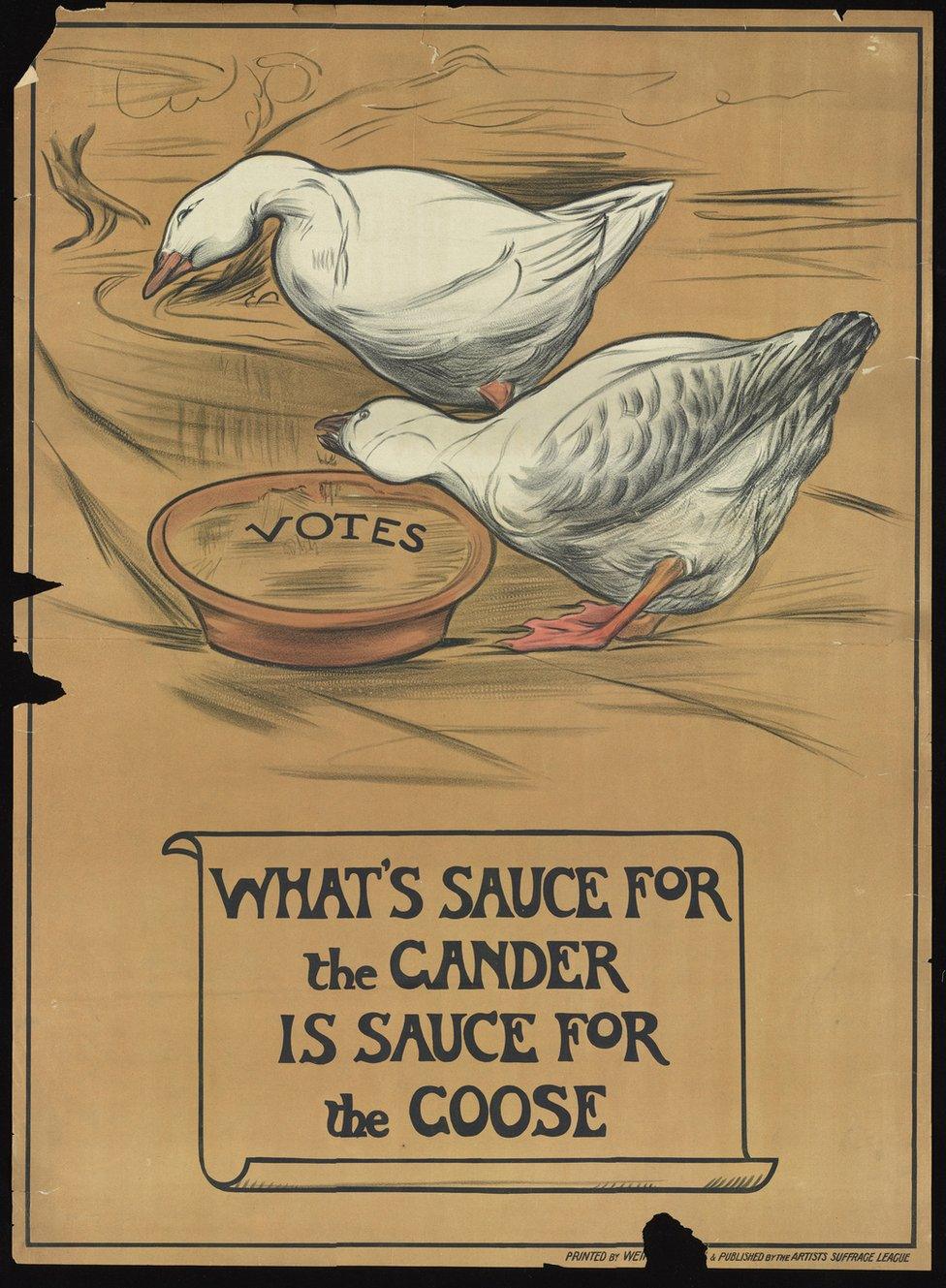

To appeal to the widest audience, Delap says, the suffrage posters took inspiration from the tabloids, using eye-catching headlines, large cartoons and photographs.

And the suffragists were media-savvy political campaigners - reacting to the policies of the day.

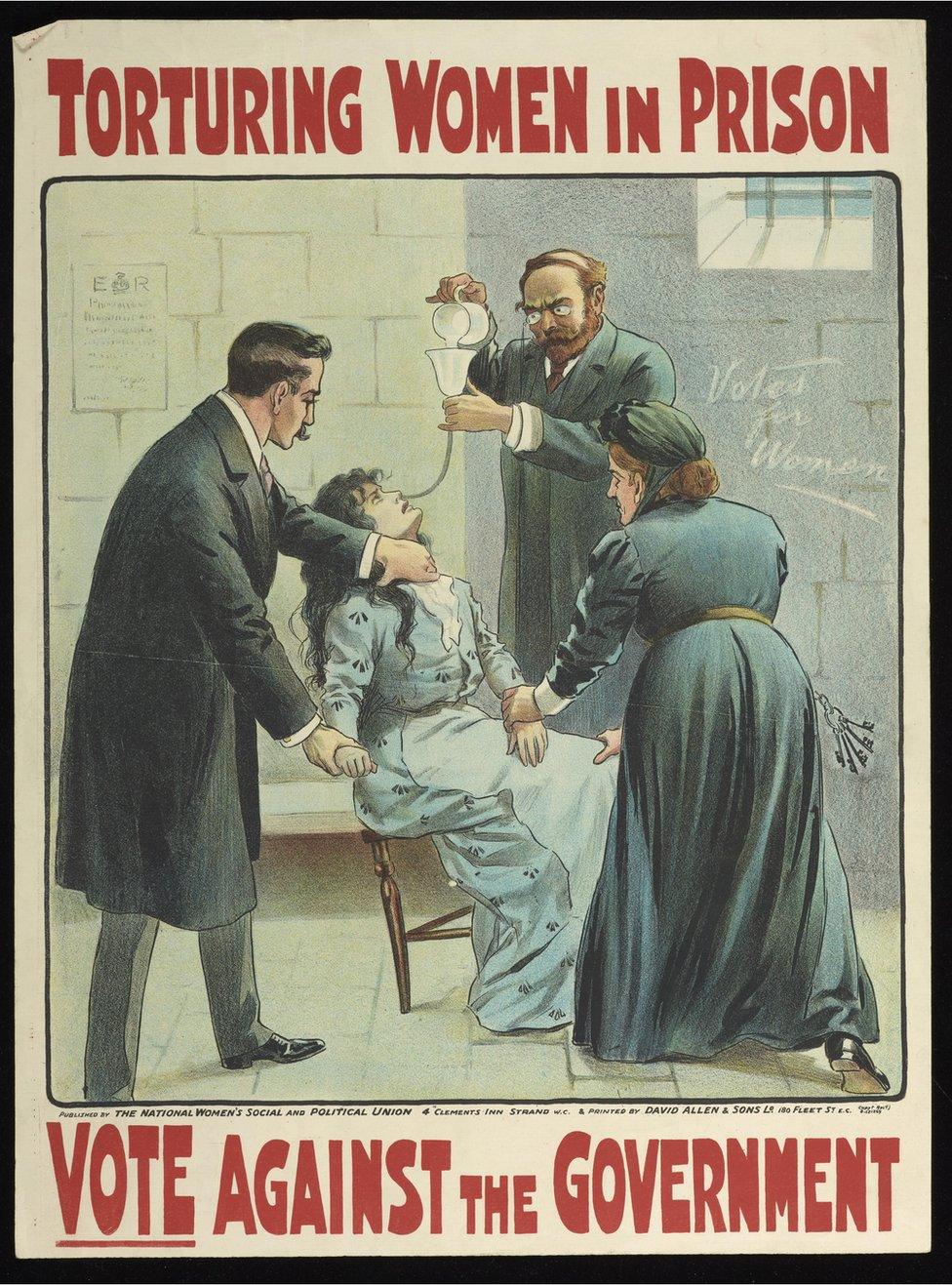

In 1909, there was a national outcry when Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone ordered that imprisoned protestors on hunger strike should be force-fed.

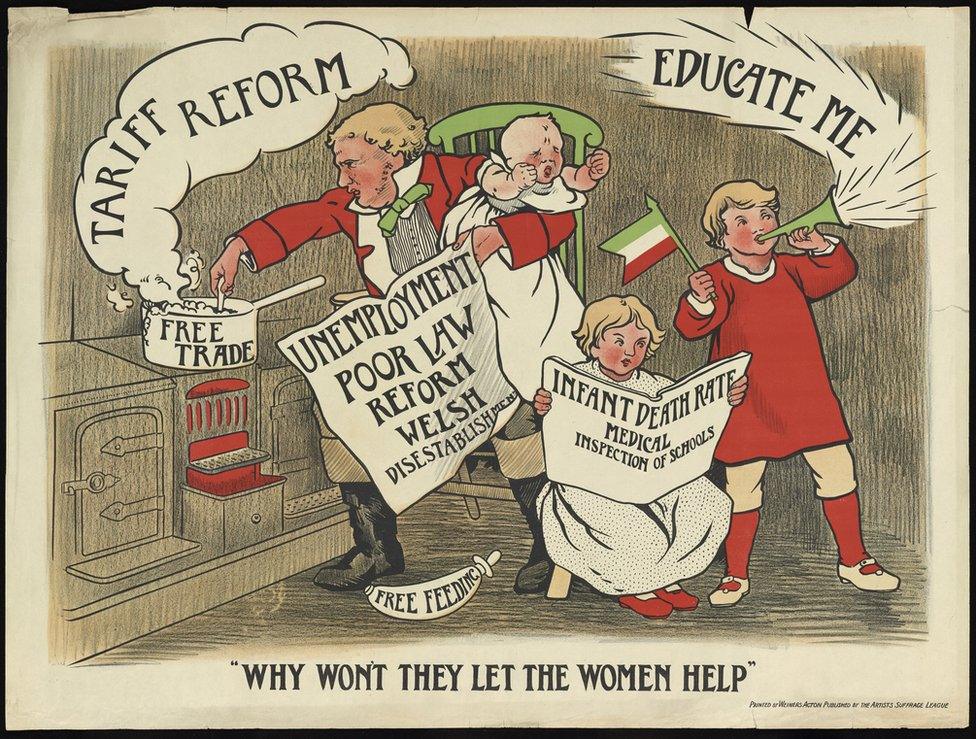

John Bull - a fictional figure commonly used to personify the UK, and England in particular - is depicted in the image above.

Without the help of a woman, he is struggling alone with children and housework, visual metaphors for the social problems of the Edwardian era.

This poster suggests if women could vote, then problems including infant mortality, poor schooling and unemployment might more easily be solved for the benefit of everyone.

"Handicapped" was one of the most popular posters of the suffrage campaign, painted by Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant.

It shows a young privileged man being easily propelled forwards by votes, while a woman struggles on choppier waters in a simple row boat.

Mrs Partington was another familiar figure used by the UK press at the time.

She was usually seen trying to stem progress with her mop.

In this case, she is trying to stop the seeming flood of support for women's votes.

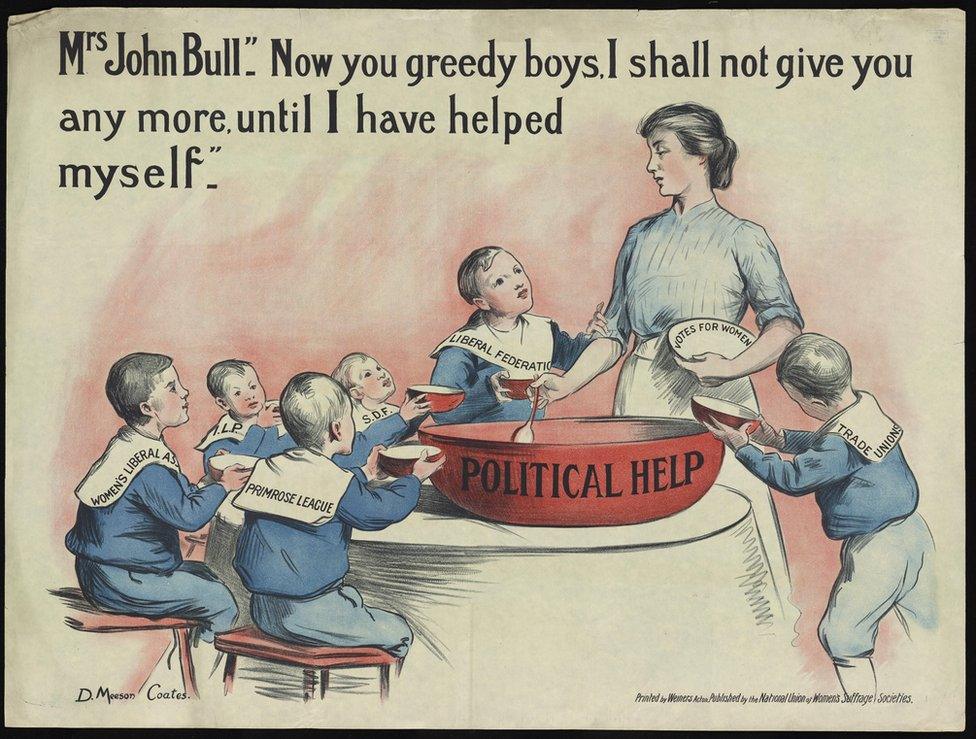

The poster below called for support for political organisations - listed on the children's bibs - to be withdrawn until women were able to participate at the ballot box.

Some posters explicitly call for "law-abiding" meetings. Delap says the movement was split over whether more violent action was needed.

"There were militants who were willing to break the law: smashing windows, destroying golf courses, burning buildings," she says.

"There were also non-violent actions that broke the law - refusing to fill in the census, refusing to pay tax without representation - a range of creative tactics.

"But just to stand on a box in the marketplace, as many women did, provoked public fury, peltings with rotten vegetables and even police brutality.

"To be a female suffrage activist of any kind was a militant act."

Our Weapon is Public Opinion: Posters of the Women's Suffrage Movement is on display at Cambridge University Library from 3 February.