Life after Ebola

- Published

It has been four years since the Ebola virus outbreak in the West African states of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone was first reported. Photographer Hugh Kinsella Cunningham has been back to document the people still living with the legacy of the disease.

The outbreak in 2014 caused more deaths than all the others combined since the virus was discovered in 1976.

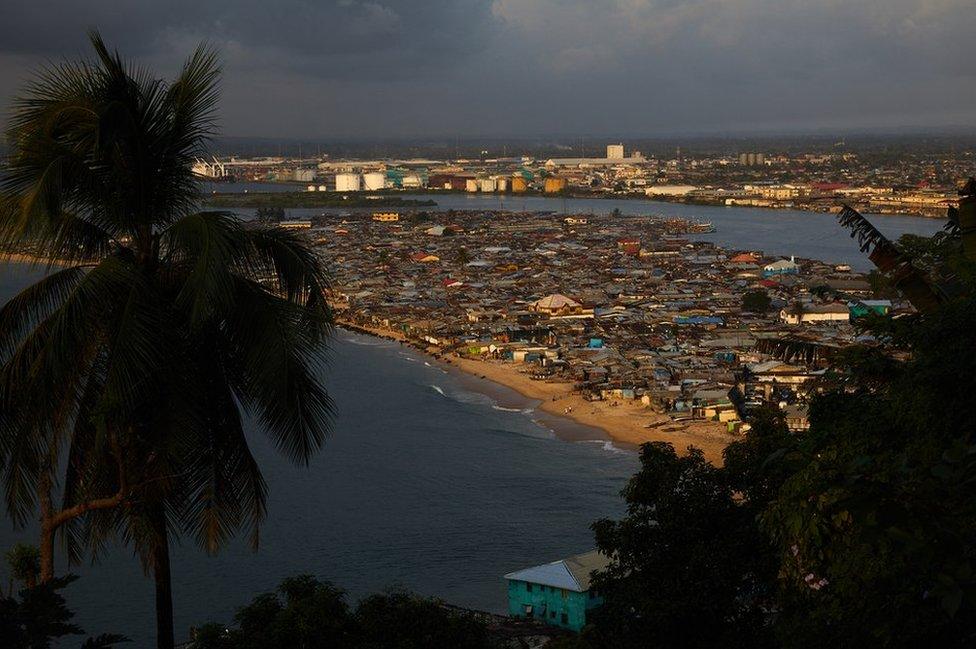

The virus affected poverty-stricken areas such as Liberia's West Point, where for many, just coping and surviving are everyday victories.

West Point is a densely populated township in Monrovia. When the government imposed a curfew and quarantined the area in a bid to halt the deadly outbreak there was unrest and rioting.

Eva Nah's grandson was killed by police while he was protesting at the quarantine. "All he wanted was to play football and become a mechanic," she says. "His father and mother died so I was everything to him."

Years on, government compensation for his killing has allowed Eva to send four other children in her family to school.

Rita Carol lost her sister to the disease. She used to sell food on the cramped roads of West Point but has saved enough to purchase a refrigerator and start a new business selling ice, which she hopes will provide a good living for her future.

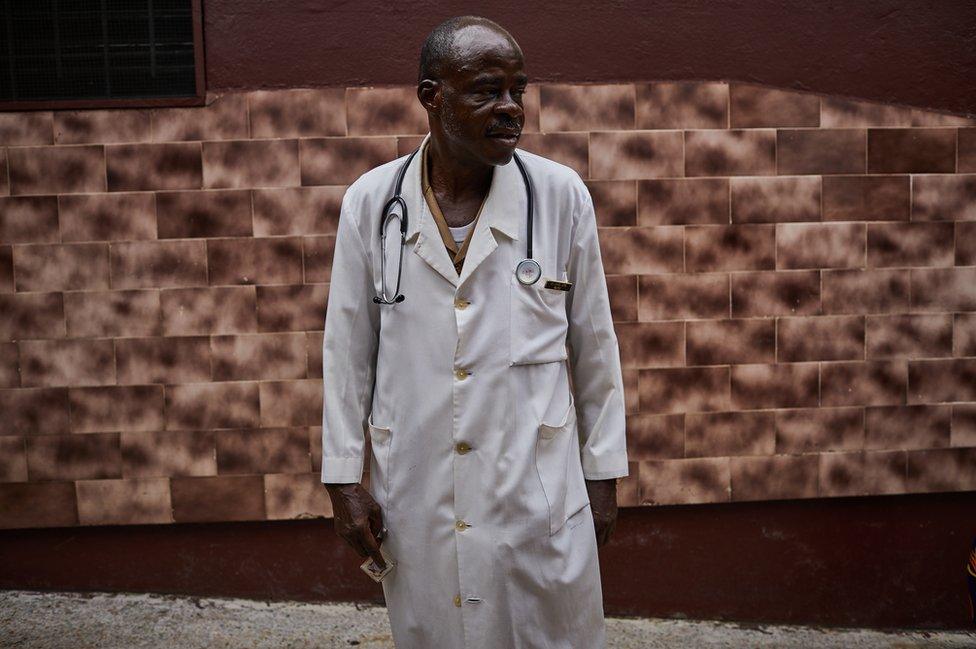

Etta Roberts works as a nurse at the Kahweh clinic, a health centre to the east of Monrovia. She usually treats around 10 patients a day for malaria and scabies.

The clinic's founder, Reginald Kahweh, funded the building of the centre after losing both his parents to Ebola, saying: "Everyone had to step up to create a better society… this place was formed to remember those who died."

The Ebola crisis was a shock to the Liberian health system, which was quickly overwhelmed. The country's infrastructure was already damaged by a 14-year civil conflict and the health services were struggling to meet basic needs.

In response, areas of high risk such as West Point are now monitored carefully for any unusual health trends and a 24/7 duty officer can raise an alert to the National Public Health Institute if a death seems medically suspicious.

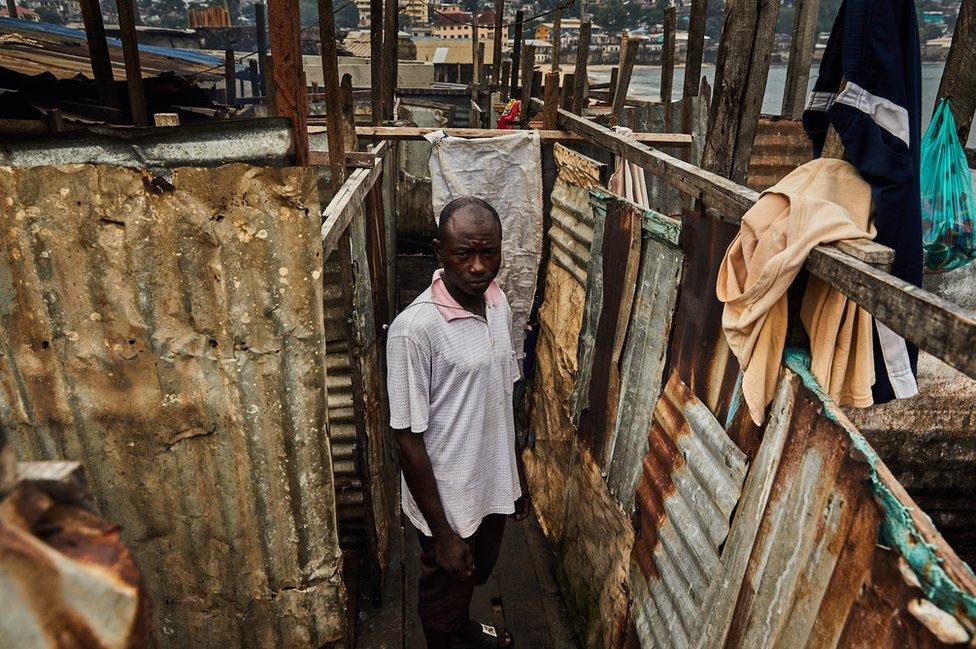

J Roberts lives by the rapidly encroaching sea in West Point. After losing his wife to Ebola he started a business. "My wife was cremated, not buried, so it feels as if she is gone forever. I decided to concentrate on our four children, money is a necessity for them," he says.

He sells heated water and the use of booths to wash in. His facility is of great value to the community due to the poor sanitation in the area.

Despite positive advances in health infrastructure and the survivors' determination to move on, several former body disposal workers have been left in a state of limbo.

Most workers involved with the burial of Ebola victims in Sierra Leone were poor and jumped at the chance of an employment opportunity that few others wanted.

Mohammed Kanu was employed by the government to dispose of bodies safely during the outbreak. No subsequent work has materialised and he finds himself still tending the overgrown graves, with little payment.

Burial ceremonies that involved contact with the bodies of the dead also contributed to the transmission of the disease and many workers face poverty and stigmatisation for their former roles. Morla Kargbo, another graveyard worker, explains: "People don't even want to rent a house to you if you were involved with bodies during the Ebola time."

All images copyright Hugh Kinsella Cunningham, external.