The British women who secretly served in the Cold War

- Published

For more than 20 years, the green plains of Holderness, East Yorkshire, were the secret location of underground bunker RAF Holmpton, where radars watched the skies amid the threat of the Cold War.

During the uncertain years of the Cold War, when nations prepared for the prospect of a devastating nuclear war, Britain created a defensive radar programme called Rotor, involving 70 radar stations dotted around the coast.

One of these was an underground bunker in the tiny village of Holmpton, built in 1953 and nicknamed "the hole".

It faced east and was able to see hundreds of miles to the Soviet Union, as the superpower stockpiled nuclear weapons.

The Cold War bunker at RAF Holmpton is now a museum. A simple bungalow (top) hides the entrance.

In the event of a catastrophic nuclear war, RAF personnel as well as ROC personnel at Holmpton would be tasked with restoring order in the region.

Workers at the bunker were also responsible for warning of an approaching attack, recording the direction, velocity and ultimate radioactive fallout of a bomb.

Nine women who worked at Holmpton and two other nearby bunkers shared their memories with photographer Lee Karen Stow.

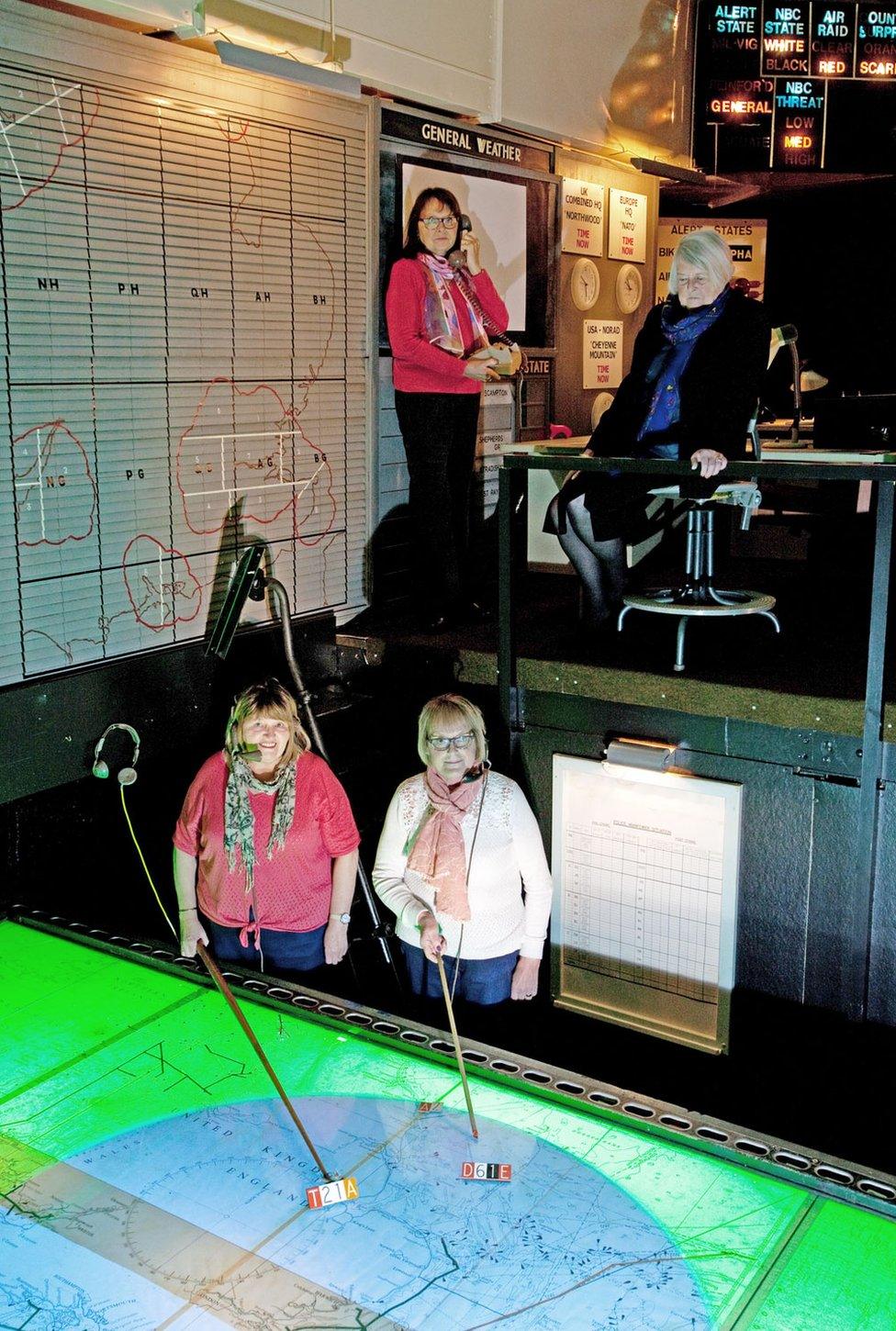

Cpl Janet Huitt (top left) and her sister SACW Barbara Turner (bottom right), SACW Eileen Mann (top right), and SACW Janet Levesley (bottom left) - pictured in the radar operations room at Holmpton - joined the RAF aged 17 and worked in the bunker at some point between 1959 and 1974.

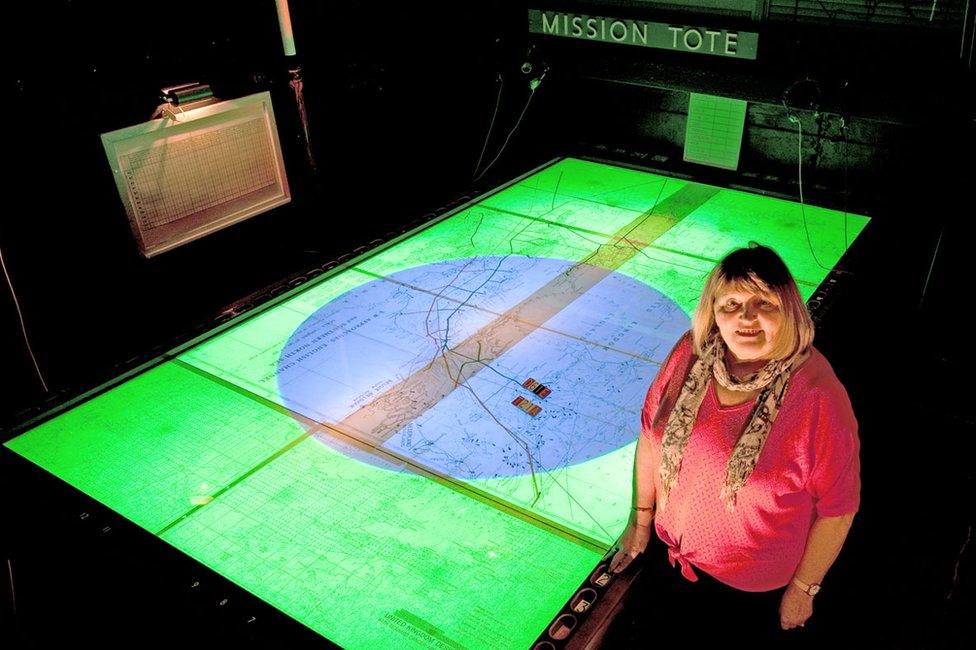

As air defence operators, the women interpreted raw data from radar screens, writing the results backwards on a clear Perspex "tote" board so they could be read from the other side.

The information would then be plotted on the radar board (seen above), which was on a lower level, known as the "well".

Officers seated above could then look down and monitor incoming enemy aircraft.

Holmpton bunker, which opened as a museum in 2004, features a 120m (400ft) tunnel

Cpl Huitt says: "I remember the noise from the vents, like a loud buzzing which you got used to, and how closed in it was.

"Every aircraft submitted a 'flight plan' and would be given a call sign.

"If anything appeared which did not have this information, it stood out like a sore thumb.

"It was picked up immediately and responded to.

"Usually one or two fighter aircraft would be scrambled from local airfields, to intercept and escort them out of our airspace.

"They usually came from the Soviet Union.

"It happened quite often throughout the Cold War period and kept us on our toes.

Cpl Huitt serving coffee to the air vice marshal in the briefing room at Holmpton in the 1960s

"We were drilled on procedure for a nuclear attack.

"We all knew if we were within range, we would not survive the fallout.

"You could be called back on duty at any time of day or night and never knew if it was real or an exercise.

"It was a 'red alert'. Buzzers went off everywhere.

"There was never any panic. You were trained and disciplined.

"If you obeyed commands and did your job, everything would be fine.

"We earned two-thirds of a man's wage. We were told it was because he could get married and have a family to support.

"In those days, you would be discharged if you were pregnant, whether married or single."

SACW Turner says: "It's really important [people know about us] because we spent all these years working down here and nobody ever recognised it, or has ever recognised it.

"Because it was secret was probably the main reason, but it's never been documented that these women all served years and years underground."

SACW Levesley served five years at RAF Holmpton as an air defence operator, known as a "plotter", who would transfer incoming data to the radar board table in the "well".

She says: "I remember having to climb down the steep, iron steps to the well in a skirt and feeling a bit conspicuous with all the male eyes looking.

"There were female officers as well, but it was mainly a man's domain.

"It was quite dark, with all the glow from the computers on their faces.

"I remember once, when I was about 18, I got a callout.

"It was about 19:00.

"I was in the kitchen, and they came for me.

"I rushed upstairs to get my uniform on.

"My dad was tiling the kitchen at the time, and he said, 'Is it worth me putting these tiles on? Are we going to get bombed?'

"It was an exercise to see how quickly we would get there if anything happened."

SACW Pat Leckonby, SACW Rosemary "Christine" Wright and SACW Trish Altoft served as telephonists in the late 1960s and 70s, operating Holmpton's switchboard.

SACW Altoft says: "You're talking about the Cold War, but I must be honest I don't suppose any of us thought about it at the time.

"All you did was take the calls.

"During the day, you were that busy. We weren't privy to any secrets.

"We were quite insular. I see us just as little cogs."

"Yes, but we were important cogs," SACW Leckonby says.

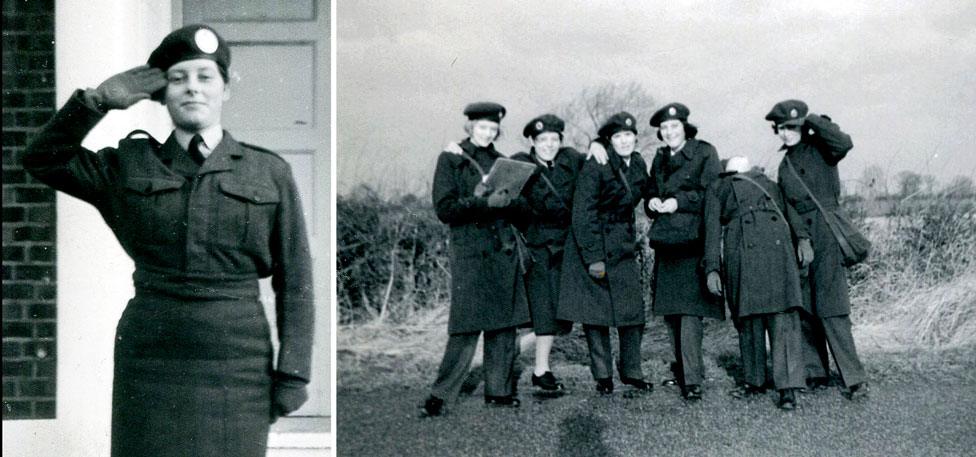

SAC Leckonby in the 1960s, and with the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (second from the left).

The bunker staff would have drills in case there was a fire underground.

SACW Altoft says: "As soon as the alarm went, everybody was straight down and out and up into the field.

"The last person to leave was the commanding officer and the senior PBX [private branch exchange] worker.

"One night, I was the last to leave. I've never been so frightened in my life, because all the lights went out, then a dim light came on.

"And that corridor - walking until we got to the light outside was absolutely horrendous.

"I was just absolutely terrified that I would get trapped in there."

SACW Leckonby says: "When the door shut - oh, I felt claustrophobic.

"It was mainly men down here. And we were very young and good looking then."

Before working at Holmpton, SACW Wright had volunteered to work at a monitoring post on the East Yorkshire coast in a bunker 14ft (4m) below the ground accessed by an iron ladder.

She says: "It was a square hole in the ground.

"At night, it was frightening. I didn't like going down there."

"There used to be two or three of us down there.

"When you first go down, you don't know what to expect and you just find this room and chair and that was about it.

"I only did [my] hours, then I went home.

"But if we'd gone to war, we'd have had to sleep down there.

"I wouldn't want to do it now.

"But when you're young, you do anything, don't you?"

Gina Wright was an ROC emergency planning officer at Holderness District Council Emergency Centre underground bunker.

She says: "As you went into the bunker, the first thing that hit you were the massive blast doors.

"The minute you went through the doors, the security footing for the nation was in front of you.

"It was a total subterranean world. It was incredible. It went on forever.

"I don't think I ever got to the end of it.

"Timed lights meant you had to really hoof it.

"I was a bit of a wimp. I didn't like going down alone.

"In time of war we would have four phases: transition to war when everything would start to happen; declaration and conventional war; nuclear strike; then the aftermath.

"So, the plans were sectioned to respond to those phases.

"The thought of the nuclear bomb dropping was something that was so surreal. You couldn't grab hold of it. I thought the war was a crazy notion. It was just too mad."

Ann Metcalfe was 17 when she joined the ROC, in 1964, and worked in the York Cold War bunker, now an English Heritage property.

In 1982 she became the first woman group officer in charge of four monitoring posts in the Yorkshire countryside and was promoted six years later to honorary observer lieutenant.

She says: "I became the triangulation supervisor, responsible for calculating the size and the position of the bombs.

"We had a circular calculation table that would calculate exactly how big that bomb had been from the reading you got from a blast."

Ann would visit each of the four monitoring posts she oversaw, 10 to 15 miles apart, to check on her teams during training exercises and drills, as well as hosting visiting dignitaries.

"At the back of your mind you were hoping [a nuclear attack] would never happen," she says.

"Because at that time I had a husband at home and two young children.

"If you were called up in an emergency, you would be called up full-time. Would you leave your family? It was always something we never knew because we were never put in that position.

"I always thought if there was a nuclear attack, I'd want the bomb to land on the top of my family house. No messing about, I didn't want them to die slowly of radiation because it was a horrible death."

Text and pictures by Lee Karen Stow

- Published28 October 2012

- Published3 December 2015

- Published10 October 2012