A secret network that helped slaves find freedom

- Published

During the late 18th Century, a network of secret routes was created in America, which by the 1840s had been coined the "Underground Railroad". The network was intentionally unclear, with supporters often only knowing of a few connections each.

Though the exact figure will always remain unknown, some estimate that this network helped up to 100,000 enslaved African Americans escape and find a route to liberation.

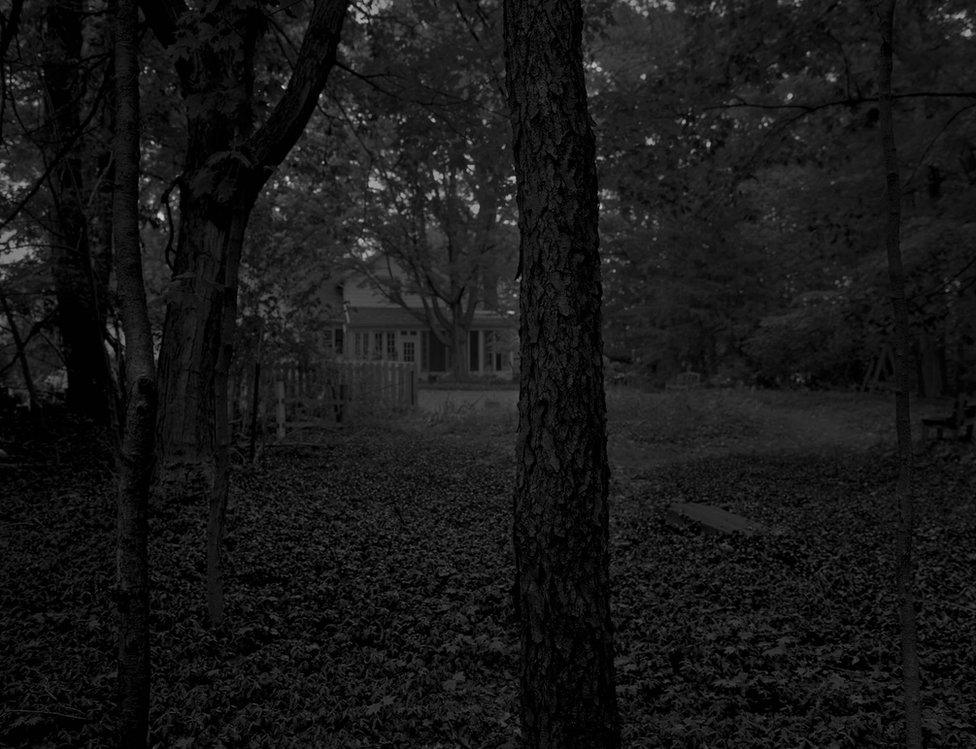

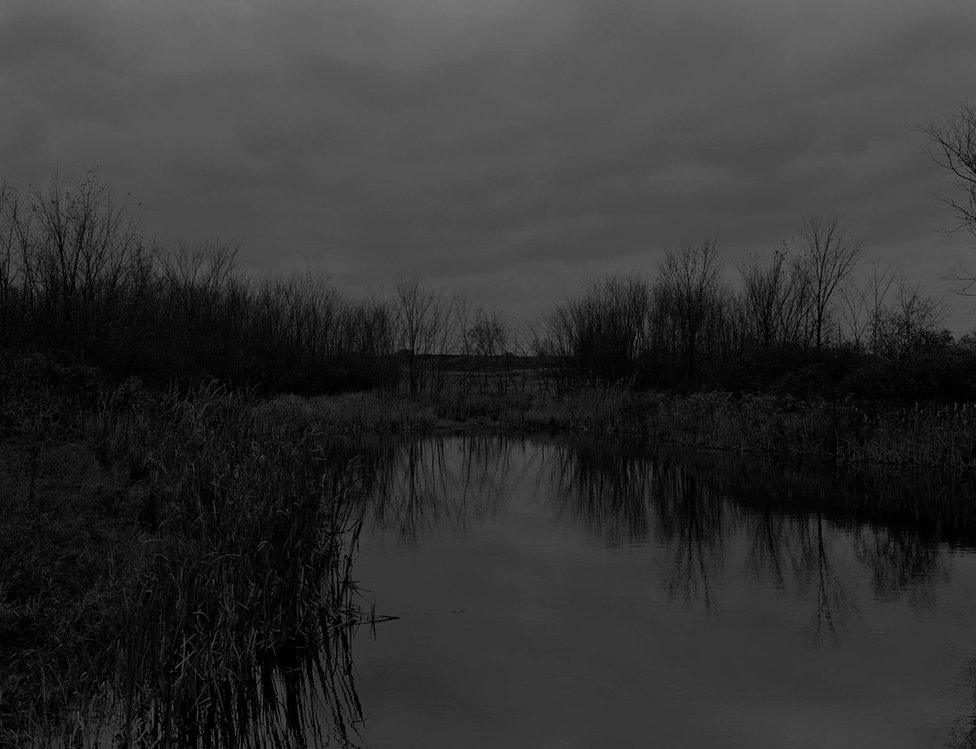

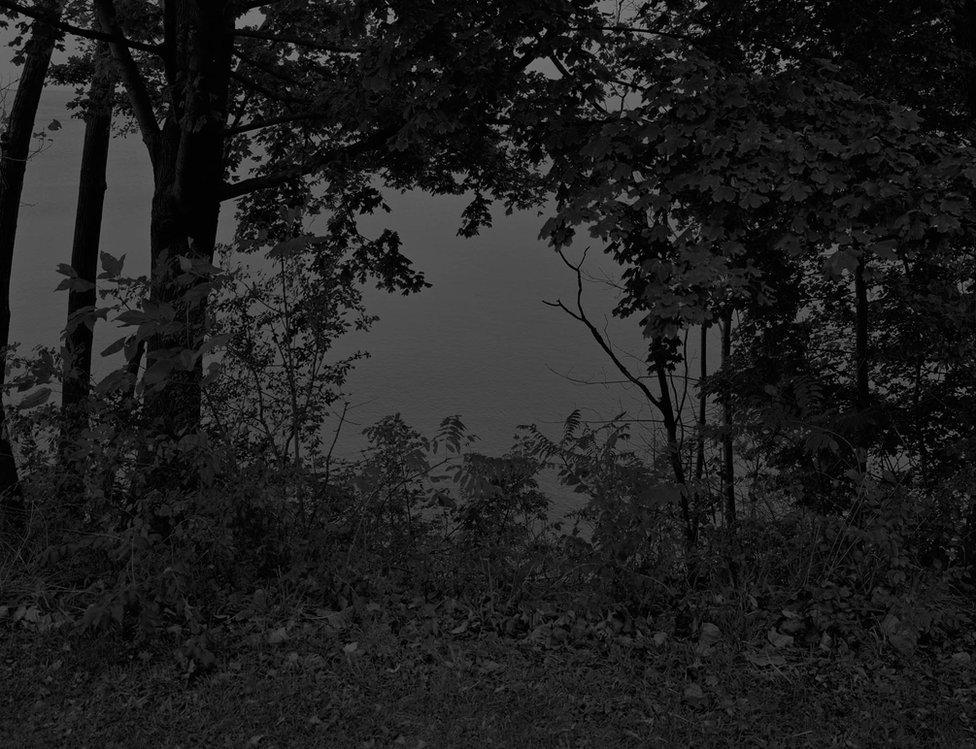

In his exhibition, Night Coming Tenderly, Black, photographer Dawoud Bey reimagines sites along the routes that slaves took through Cleveland and Hudson, Ohio towards Lake Erie and the passage to freedom in Canada.

There were also well-used routes across Indiana, Iowa, Pennsylvania, New England and Detroit.

With influences from the photography of African American artist Roy DeCarava, where the black subject often emerges from a subdued photographic print, Bey uses a similar technique to show the darkness that provided slaves protective cover during their escape towards liberation.

Unlike what the name suggests, it was not underground or made up of railroads, but a symbolic name given to the secret network that was developing around the same time as the tracks.

This allowed abolitionists to use emerging railroad terminology as a code. Both black and white supporters provided safe places such as their houses, basements and barns which were called "stations". Those who hid slaves were called "station masters" and those who acted as guides were "conductors".

Spirituals, a form of Christian song of African American origin, contained codes that were used to communicate with each other and help give directions. Some believe Sweet Chariot was a direct reference to the Underground Railroad and sung as a signal for a slave to ready themselves for escape.

In 2014, when Bey began his previous project Harlem Redux, he wanted to visualise the way that the physical and social landscape of the Harlem community was being reshaped by gentrification. He says it was a fundamental shift for him to form a mental image of the experience of space and the landscape, as if it was from the person's vantage point.

Bey says he has pushed that idea even further in this project, trying to imagine the night-time landscape as if through the eyes of those fugitive slaves moving through the Ohio landscape.

"I've never considered myself 'a portrait photographer' as much as a photographer who has worked with the human subject to make my work," says Bey.

One of the most famous conductors of the Underground Railroad was Harriet Tubman, an abolitionist and political activist who was born into slavery. During her life she also became a nurse, a union spy and women's suffragette supporter.

She initially escaped to Pennsylvania from a plantation in Maryland. Afterwards, she risked her life as a conductor on multiple return journeys to save at least 70 people, including her elderly parents and other family members.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed local governments to recapture slaves from free states where slavery was prohibited or being phased out, and punish anyone found to be helping them.

After its passing, many people travelled long distances north to British North America (present-day Canada). The network remained secretive up until the Civil War when the efforts of abolitionists became even more covert.

"There was one moment when I was photographing at a bluff [a type of broad, rounded cliff] overlooking Lake Erie that was different from any other I'd had over the year-and-a-half I was making the work," says Bey.

"Standing at that location, and setting up to make the photograph, I felt the inexplicable yet unseen presence of hundreds of people standing on either side of me, watching. At that moment I knew that this was an actual site where so many fugitive slaves had come."

Dawoud Bey's exhibition Night Coming Tenderly, Black, external is on show at the Art Institute of Chicago, USA until 14 April 2019.