Glimpsing a world beyond human extinction

- Published

Stand on solid ground and look down at your feet. Go deeper - through the flesh and bones, deeper into the Earth. What's down there? It's hard to imagine, let alone visit - should you want to.

Writer and explorer Robert MacFarlane has been voyaging in this hidden world, going back in "deep time" to places measured in "millennia, epochs and aeons, instead of minutes, months and years".

Now, he has surfaced and is asking: "What will we leave behind when we are extinct?"

And he is telling us why we should care.

To MacFarlane, this image could be "an annunciation scene from Giotto".

But look more closely - in fact, it's an "avalanche of vehicles".

He abseiled down into an abandoned Welsh slate mine where locals have been dumping wrecked cars for 40 years. He says: "We are not just shaping the surface, but shaping the depth."

Will our future fossils just be "car-chives" like this, along with the inevitable strata of plastic, lethal nuclear waste, and the spines of millions of intensively farmed cows and pigs?

Or can we, as a species, start to do things better?

As a Swedish teenager, Greta Thunberg, inspires worldwide climate-breakdown protests, and Extinction Rebellion brings central London to a standstill, it seems a good time to be looking at what MacFarlane calls the "under-land", and to be asking ourselves: "Will we be good ancestors?"

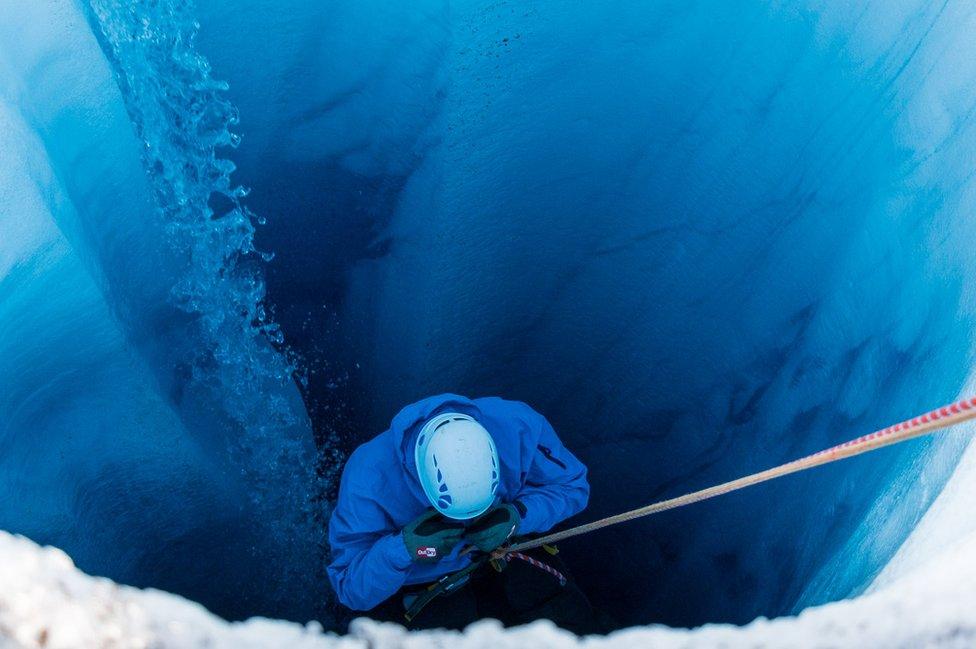

Ice, says MacFarlane, "holds incredible knowledge". So, in 2016, after the warmest summer on record in the Arctic, he dropped down into a fissure in a melting glacier to learn lessons from it.

Shafts in the ice such as this one, in the Knud Rasmussen glacier on the east coast of Greenland, are called "moulin" (the French word for "mill"). They are formed when the ice thaws and meltwater bores its way in. Scientists now use them to measure how quickly the glaciers and the ice caps are thawing.

Entering through its mouth, MacFarlane dropped 60ft (18m). He had time to look around, to be astonished, before getting caught in the torrent of meltwater and giving the agreed signal to "get me... out of here".

The deeper you go, the deeper the blue - and the older the ice. MacFarlane says: "As you drop down, you drop further back in time." In a few minutes, he had travelled several hundred years.

"It felt like being inside a vast alien creature… a humming blue tube," he says.

MacFarlane says he was "calm and serene" - before being spun out of control. "It was beautiful," he says, "except when I was getting absolutely hammered by the meltwater stream, penduluming me out and smashing me back in."

Climate change is making the glaciers retreat so quickly that, according to MacFarlane, locals in the tiny settlement of Kulusuk, in Greenland, now can't hear when it "calves" - when vast pieces of it shear off. Not so long ago, this sporadic thunder used to be part of their soundscape.

MacFarlane says: "The sense of rapidity and change up there is enormous."

He forms a globe with his hands, representing the Earth and its ice-covered poles, and says of rising sea levels: "At the moment, the fate of the ice is the fate of us."

Claire Marshall talks with Robert MacFarlane in Epping Forest

But it's not, thankfully, a tale entirely about looming annihilation. MacFarlane says he didn't have to travel far from his home, in Cambridge, to find a world "humming with mystery and miracle".

In Epping Forest, I hear about his walks there with an ecologist who taught him about the "wood wide web", a name given to the subterranean relationship between plants and fungi - also known as the "kingdom of the grey".

Robert MacFarlane explores an upturned tree in Epping Forest

He smiles at the softness of the spring beech leaves. "An extraordinary social network is happening just 20cm [8in] under our feet," he says.

"Rather than a lot of individual trees, it is a community.

"Knowing this changes the ground you walk on."

The human world wide web has existed for less than 30 years.

The roots of plants and fungi mycorrhizal have been communicating with and helping each other for 400 million.

It clearly works - fungi were the first organisms to return to the blast site around Hiroshima. They seem to be in no danger of going extinct.

MacFarlane believes that learning from the wood wide web, learning to "speak in spores", could help save humans.

Gaze down in to Onkalo, a nuclear fuel repository in Finland, designed to bury something that needs to be kept from humanity forever - nuclear waste.

Onkalo means "The Hiding Place." Its chambers are being excavated 1,500ft below ground, inside 1.9-billion-year-old rock on the west coast of Finland.

Surely a deeply depressing place to visit? But MacFarlane says that he was "oddly and unexpectedly lifted".

Radioactive waste can remain dangerous to humans for tens of thousands of years.

This structure will need to outlast the people building it - by millennia - perhaps even the species that designed it.

MacFarlane says: "I went there expecting apocalypse, to be the darkest place that I had ever reached, where we put the worst we have ever made - but it was one of the most hopeful places I ever reached."

"It was an example of cooperation and communication.

"It's an incredibly complex task - the pyramids have only lasted 5,000 years.

"And there was a sort of success that was born of deep time thinking engineering, scientific expertise and community cooperation.

"The thinking that is being done at Onkalo is an example of how to be good ancestors.

"And that is a question we need to be asking ourselves all the time now."

MacFarlane also met some of the denizens of the "invisible city" below Paris.

There are 200 miles of catacombs and quarries beneath the streets of the the French capital.

He spent three days navigating the labyrinth, sometimes having to turn his skull sideways to go "lizarding" forwards. It was the longest he had spent without sun or sky.

MacFarlane likens this sculpture to humanity's current existential struggle with climate change.

"This figure is half stepping out of ancient stone and half into the air of the present, half caught between these two states, unable to advance or retreat," he says.

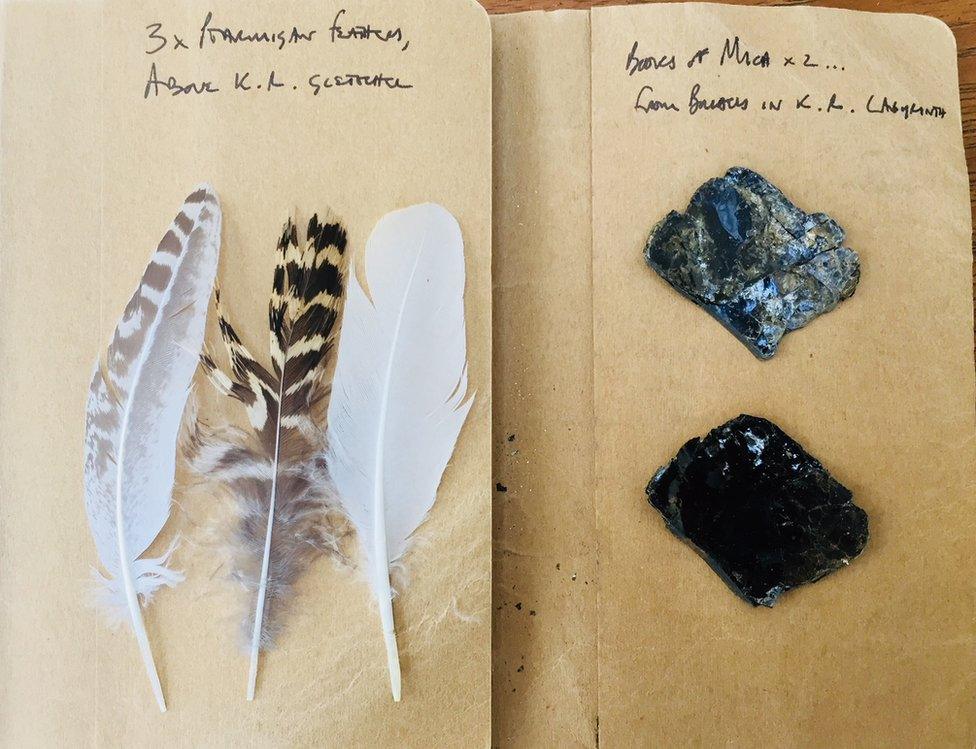

These are notebooks from a decade of underland exploration: words also written during the hunt for the origins of the universe in an ice laboratory beneath the Yorkshire moors, while deep in ancient mines in the Mendip Hills, mountaineering to a remote Arctic "cave-art" site in Norway, and descending to a "starless river" in the Slovenian highlands.

Having now shaped all this in to a book, called Underland, hasn't he ended up wondering why we should bother caring about how we live? Humans will just die out soon anyway.

No. MacFarlane believes that a deep time awareness should, at its best, "provoke us to action not apathy".

It should help us, he says, "to see ourselves as part of a web of gift, inheritance and legacy stretching over millions of years past and millions to come, bringing us to consider what we are leaving behind for the epochs and beings that will follow us".

An artist carved this owl from the rib bone of a minke whale, washed up on a beach in the Hebrides.

He gave it to the writer on one condition - that he carry it with him as a talisman, to help him see in the dark.

Did it work?

"Yes," he says, "in that I learned not just how to see in the dark but also to see the dark, as it were."

And?

"We are a brilliant, terrible species."

Photographs all subject to copyright.