World Toilet Day: The lives of Indian sanitation workers

- Published

Sudharak Olwe has been documenting the lives of Mumbai's sanitation workers for about two decades.

The work, often in appalling conditions, is reserved for Scheduled Castes, officially designated groups of historically disadvantaged communities that live on the fringes of society.

And their lives remain substantially unchanged despite India's overall economic, social and technological advancements.

Olwe's most recent photographs, commissioned by WaterAid, are shown as part of UN World Toilet Day 2019.

"Manual scavengers" from the Valmiki community remove excrement by hand from dry latrines in Amanganj, Panna, Madhya Pradesh.

Betibai Valmiki says: "We are not allowed to drink tea in any restaurant here.

"Even if we go to one small tea-shop, we are served in disposable plastic glasses while others are served in regular tumblers."

Most of the women have asthma and malaria - but there is no healthcare and their wages are docked if they call in sick.

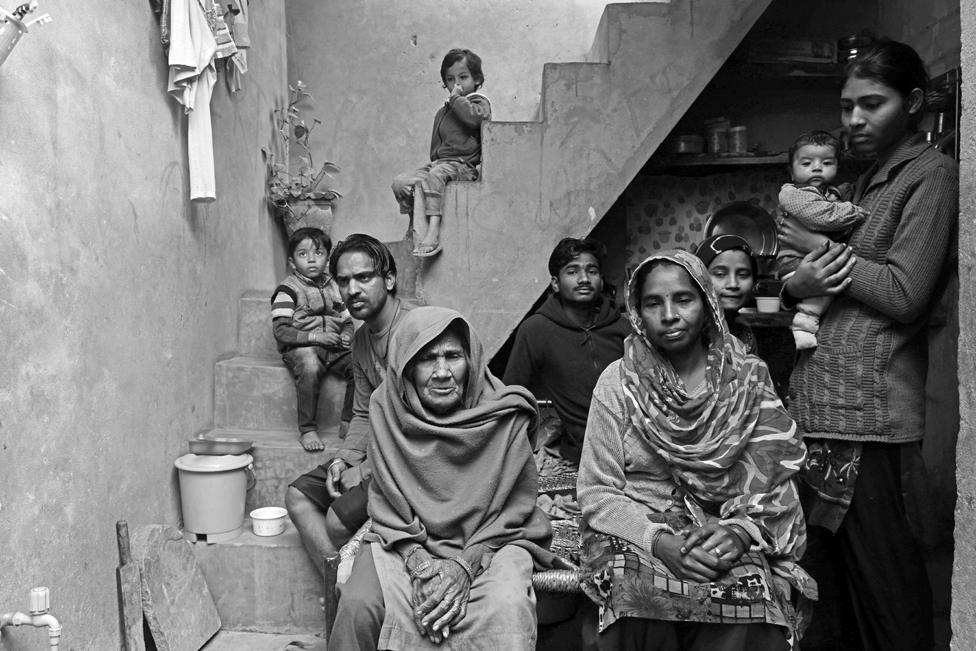

Mukeshdevi, 42, pictured with her husband, Sukhraj, mother in-law, five children and two grandchildren, in Bhagwat Pura, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, earns 2,000 rupees (£20) a month.

"What other option do we have?" she asks.

"Even if we open a shop, no-one would buy from us because we are Valmikis."

Santosh works in Amanganj with his wife and two sons.

In 1992, he nearly drowned cleaning a septic tank with colleagues, one of whom died.

It was much deeper than they had been told.

But despite his eyes being permanently damaged, he has never received any compensation.

Printed on the back of his jacket are the words "Being Human".

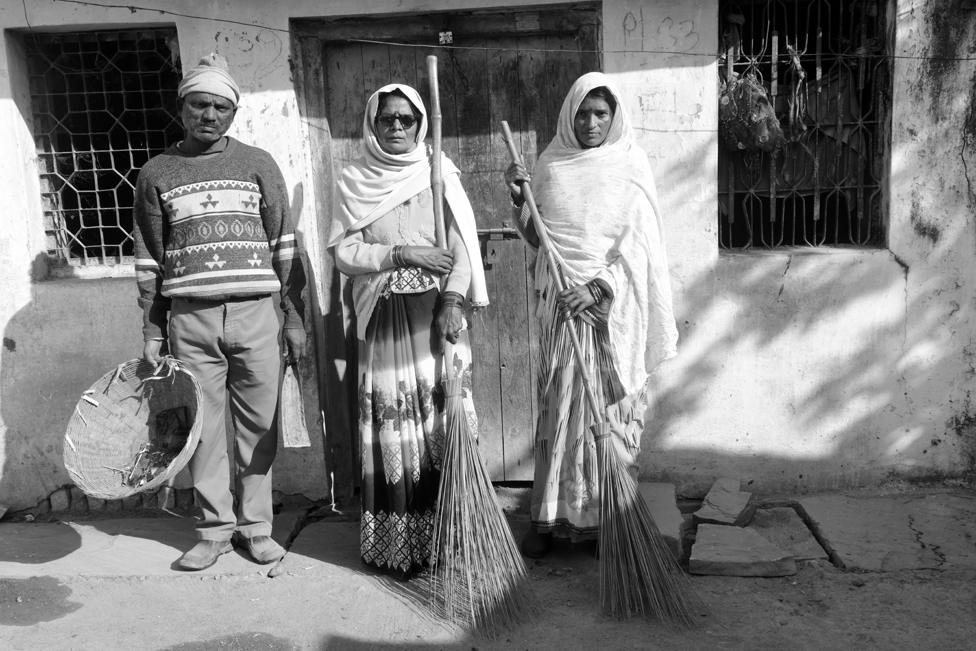

In Agra Mohalla, Panna Geeta Mattu, Sashi Balmeek and Raju Dumar work every day from 05:00 to 13:00 for 7,000 rupees a month.

"There is hardly any respect in it," Geeta says.

"We are treated so badly. It's such a thankless job."

In April last year, the Dom community on the outskirts of Thillai Gaon, Bihar, lost 10 houses and most of their cattle in a fire.

They work in nearby Sasaram but, having lost their ID and ration cards, received no help or compensation.

Meenadevi, 58, carries excrement from a Muslim neighbourhood in Rohtas.

She started working as a manual scavenger 25 years ago with her mother-in-law.

"Initially, I used to feel nauseated," she says.

"I wasn't ready and felt ashamed to work because of the stigma attached to it.

"But now I'm used to the foul smells.

"Poverty leaves you with no option.

"My mother-in-law died doing this job.

"She used to carry the sewage in tin cans. I did the same.

"Now, we don't use tin cans. Nonetheless, the same fate awaits me,"

All photographs copyright Sudharak Olwe and WaterAid