The Cashmere crisis in the Himalayan ice desert

- Published

British photographer Andrew Newey has documented the lives of the Changpa nomads in Kashmir, examining the threats to their Pashmina wool production.

Changra goats being herded back home after a long cold day in the mountains

Andrew Newey spent two weeks with the Changpa nomads in freezing conditions in Ladakh, in Indian-administered Kashmir.

To accompany his photo series, Newey also learned about the history of Pashmina wool production, and the threats to the nomadic shepherds' way of life and traditions.

He explains in his own words: "At an altitude of more than 14,000ft, where winter temperatures can fall to -40 degrees Celsius, it is hard to believe anyone or anything can survive in this vast ice desert that is the Changthang Plateau.

The Ladakh Range has an average height of about 6,000 metres. The mountain ranges in the region were formed over a period of 45 million years by the folding of the Indian Plate into the stationary landmass of Asia

"Situated between the Himalayan and Karakorum mountain ranges, it is the highest permanently inhabited plateau in the world, and home to an extremely hardy and rare breed of goat - the Changra, or Pashmina goat.

The Changra goats are perfectly at home in the high mountains, but when heavy snow falls and freezes, their food becomes difficult to get to. The Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council provides fodder and food supplements to avoid starvation.

"The high altitude, freezing temperatures and harsh bitter winds in this unforgiving mountainous region are essential to stimulate the growth of the goats' super-soft undercoat.

"The fibres measure a mere eight to 10 microns in width, making it around 10 times finer than human hair and eight times warmer than sheep wool.

"This luxurious fibre is known the world over as Pashmina, the softest and most expensive type of Cashmere wool in the world.

A herder prepares his Changra goats to rest for the night, before continuing their journey the following day

"For centuries the Changpa nomads, who themselves are as hardy as their animals, have roamed 'the roof of the world', moving their herds of yak, sheep and goats along traditional migratory routes in this high altitude desert every few months, in search of fresh grazing pastures.

A Changpa nomad, named Lobsang, stands proudly in front of his winter house. The yak skin on the left will be dried out and the hair used to make a tent to live in during spring and summer in the Zara Valley

"This ancient way of life is now very much under threat from climate change, fake Pashmina imports from China, the need for better education and the desire simply for an easier and more comfortable life.

Village elder Bhuti is seen wrapped up against the icy wind of the plateau

The herders use the least stubborn yaks as transportation

"The nomads and scientists alike are adamant that climate change is the biggest threat to Pashmina production in the region.

"The Changthang plateau does not usually get much snowfall, and if it does, it begins in January or February.

"However, for the last few years it has been increasingly heavy, starting as early as December, even November.

"As a result, food supplements have to be brought in to prevent the animals dying from starvation. Also, the winters have been getting warmer, which has reduced the quality and quantity of the valuable Pashmina wool.

Shepherdess Dorjee leads her goats over a ridge and into the valley below

"Cashmere is expensive, and rightly so. The Changpa carefully comb the hair during the spring moulting season to harvest the downy undercoat, and then the good fibre is laboriously separated from the bad by hand.

The goats naturally begin shedding their hair in the spring moulting season and herders harvest it using a special comb, to prevent it being dropped all over the mountains

As with the combing and harvesting, the hair is also processed by the men. This involves the time-consuming job of separating the coarse outer hair from the finer soft undercoat

The wool from a single Cashmere goat amounts to a mere four ounces

"Once the fibres are manually sorted, cleaned and hand-spun, the weaving process can begin, which is equally demanding and painstaking.

Changpa women who have given up the nomadic herding life, spend much of their time weaving in the back yards of their houses in the Changpa neighbourhood Kharnak Ling, 180km (110 miles) from the Changthang plateau

"It takes several months to a year for highly skilled artisans to work their magic on wooden looms and weave a masterpiece which will be exported around the world, selling for between £150 ($200) and £1,500 ($2,000) by luxury retailers.

The finished product: Pashmina shawls, also referred to as stoles, on sale in a high-end Cashmere store in Delhi

"Another issue of concern is the increasing number of snow leopards in the region, putting their animals at increasing risk of attack. This is a result of the successful conservation efforts over the last decade.

A shepherd with his goat herd

"The threat to Pashmina goat-rearing would mean the end of the livelihoods of about 300,000 people in the Jammu and Kashmir state who, directly or indirectly, depend on Pashmina.

"It would also mean an end to the unique culture of the Changpas; most of them are followers of Tibetan Buddhism, and have an elaborate set of customs centred around their livestock."

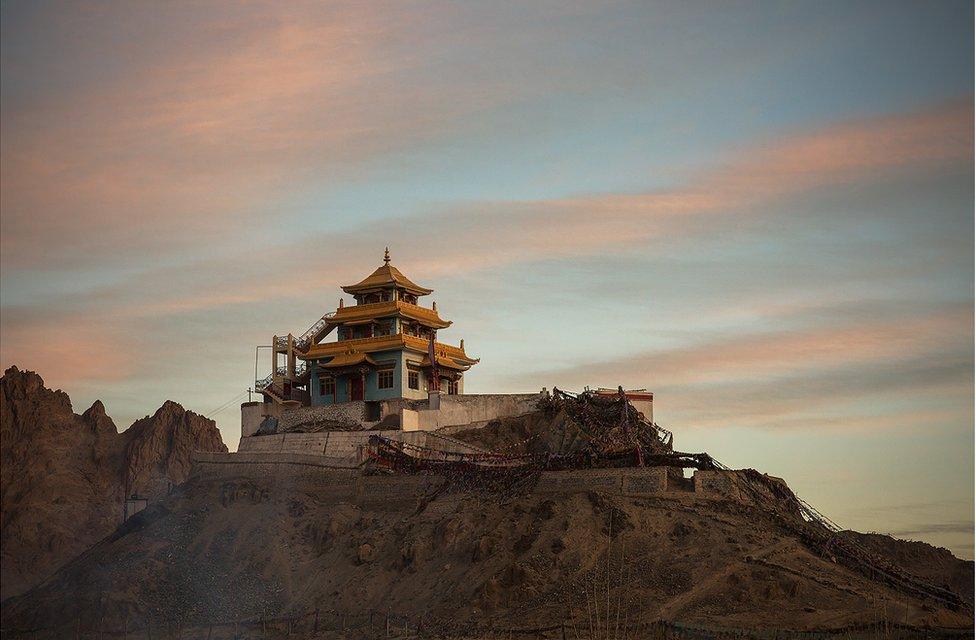

A Buddhist temple sits on a hill overlooking Kharnak Ling, the Changpa neighbourhood on the outskirts of Leh city, where families who have given up the nomadic herding life now live

First light strikes Stok Kangri, the highest mountain in Leh, at 6,154m (20,190ft)

A shepherd and his herd set out in search of fresh grazing pastures

.