Windsor Castle: Changing hundreds of royal clocks

- Published

As the clocks go back this autumn, the horological conservator at Windsor Castle will be busy changing more than 400 clocks from the Royal Collection Trust.

For those of us with smartphones and smartwatches, the change to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) on Sunday 25 October will happen automatically whilst we sleep.

But for the hundreds of clocks in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, each one will need to be changed by hand to ensure accurate timekeeping for visitors and residents.

Fjodor van den Broek is the current horological conservator of the 900-year-old royal castle.

The changing of the clocks this autumn will be Fjodor's first since taking on the role.

He plans to spend about 16 hours over the weekend changing all 400 clocks on the Windsor estate, including about 250 in the castle itself, along with seven tower clocks.

"It's just myself, and I have one colleague at Buckingham Palace who changes all the clocks there," Fjodor told the BBC.

For some clocks there is an extra time difference to take into account.

"People are still amazed that at Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace there is a small time zone in the kitchens, where the clocks are always five minutes fast.

"This is so that the food arrives on time... it's a constant reminder that this is important."

When he's not changing the time, Fjodor's job includes spending one full day a week winding up the mechanical clocks to keep their pendulums swinging.

On a typical day of walking around the castle and winding clocks, the step counter on his watch will record about 16,000 steps.

"I check all the clocks in the state apartments before the public arrive to make sure they're on time."

The state apartments are where the Queen hosts official visits by heads of state from other countries, investitures and awards ceremonies.

"Most of the clocks are quite accurate but every now and then, for no reason, they will suddenly start losing or gaining time - something which I've just started calling 'life'.

"So I do have to keep a constant eye on them."

The rest of his week is spent in his workshop servicing and repairing clocks, many of which are 200 to 300 years old.

When a part breaks or wears out, Fjodor makes a replacement using a lathe, a milling machine and lots of hand tools.

"[It has been said that] clocks were a way to bring God into your house, because God made time, and man made a machine to capture time," explains Fjodor.

"They were the supercomputers of their time.

"Now we buy a really modern smartphone, but back then if you wanted to show off you bought the latest clock."

One of the clocks Fjodor looks after is an ornate French clock in the State Dining Room.

Said to have been Queen Victoria's favourite, the clock was presented to the monarch in 1844 by King Louis-Philippe of France.

A portrait of Queen Victoria hangs behind it.

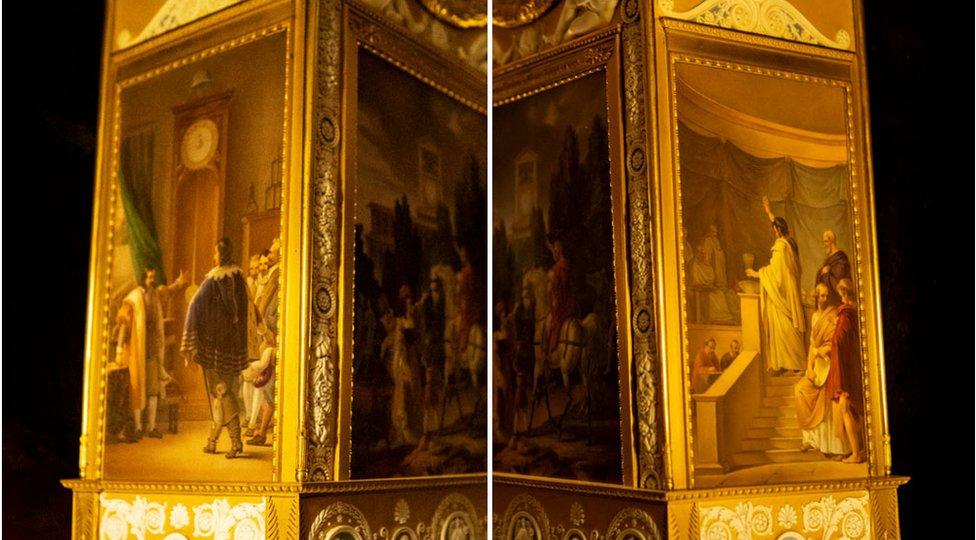

The clock features three paintings that represent the three ages of horology (the art of making clocks).

On the front there is the first astronomical clock in the town hall of Padua, Italy, in 1364.

On the left side the Dutch physicist Christian Huyghens is depicted demonstrating the first pendulum clock, which he invented in 1656, and on the right side there is a Roman senator holding a water clock.

The rest of the case is decorated with leaf wreaths, medallions and figures of famous clockmakers.

The porcelain inlays around the paintings were made in the famous Sèvres porcelain factory in Paris, a leading producer in Europe.

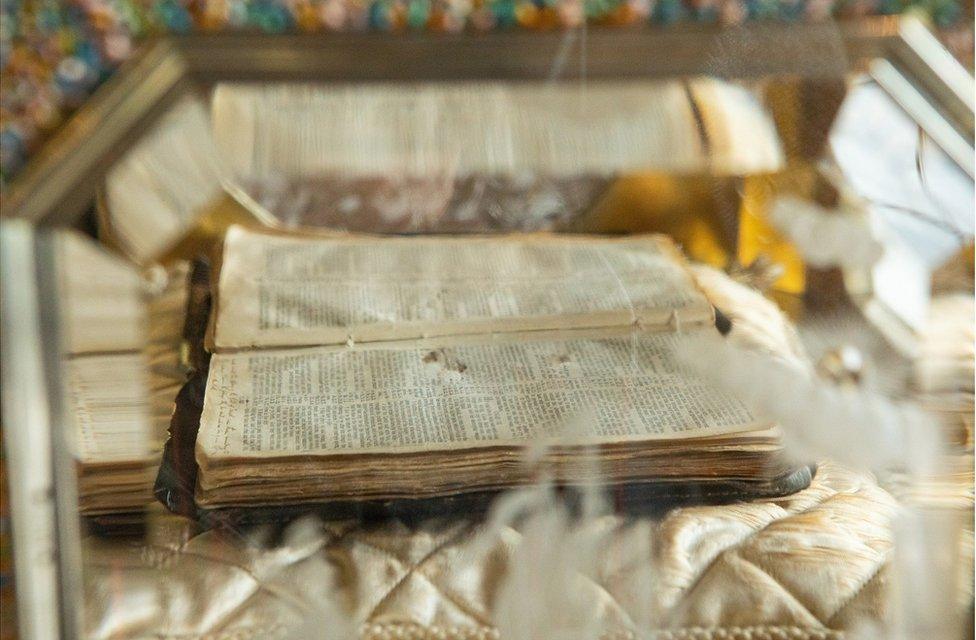

Another clock linked to Queen Victoria's reign is a large organ clock in the King's Drawing Room, which houses a Bible placed by the monarch inside a rock crystal casket.

Measuring about 6ft (1.8m) in height, the organ clock was made by Charles Clay in 1740 and plays melodies by Handel, four of which were composed just for the clock.

Clay and Handel often worked together in creating organ clocks, a number of which went to royal families in Europe.

"This is more an instrument than a timepiece, it was meant to be heard," says Fjodor.

Inside the clock base is the brass drum and pins of the organ, along with bellows that blow air through the flutes.

The Bible in the casket was owned by General Gordon, who was killed at Khartoum in 1885.

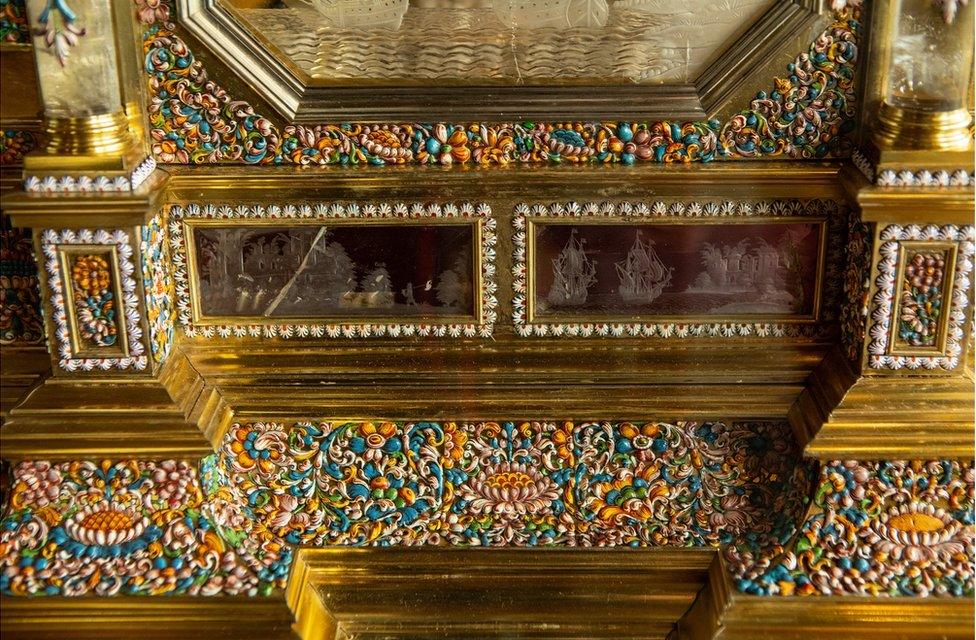

The casket was made by Melchior Baumgartner, who wrote in German on a panel inside: "[I] made this casket in Augsburg and covered it with silver in the year 1664."

The rock crystal panels are engraved with land and seascapes, and surrounded by floral-painted enamel.

At each corner is a gilt bronze figure of a Greek goddess.

On the very top is a depiction of St George and the Dragon by Francesco Fanelli, which was added during King George IV's reign in the 19th Century.

One of Fjodor's favourite items from the collection is an arresting clock that depicts the Greek mythological figures of Chronos (Father Time) and Study, with Chronos's scythe pointing to the current time on a rotating globe in the centre.

"It's a very dynamic scene, there's a lot of movement there.

"At first glance this is a statue, a piece of art, then secondly you see it's a clock."

Study is holding an open book and is surrounded by objects of learning: a lyre, an artist's palette and a protractor.

"I've seen multiple depictions of this clock and they all have a slightly different explanation behind them. Some show Study stopping Time, others are Time stopping Study."

The figures are made of bronze and the base is marble, with the clock weighing about 200lb (90kg).

"Moving this clock is a three-man job.

"We have a trolley that can lift itself to the level of the mantelpiece, you then put it on Teflon sliders to move it on to the trolley without damaging the nice marble mantelpiece.

"In the 19th Century it would have taken a couple of people with strong backs to move it."

The front of the clock is inscribed with the name of the French maker of the original clock movements, Charles-Guillaume Manière.

"It's one of my favourite clocks in terms of performance, because I serviced it three months ago and since then it has kept perfect time, within a minute."

Another timepiece that pays homage to learning, specifically the arts, is a mantel clock in the Crimson Drawing Room.

The Greek god Apollo is seen with a sculpted head at his feet and Artium Genio written on the front, meaning the genius of arts.

The clock was commissioned by King George IV when he was the Prince of Wales, evidenced by the three feathers emblem on the front.

The case was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire, a Parisian bronzeur and gilder of the early 19th Century, and the inner movements were made by Benjamin Vulliamy, clockmaker to King George III from 1773.

The striking mantelpiece surrounding this clock was made by Vulliamy's son, George John Vulliamy, a bronze castor and architect who also made the dolphin lampposts seen along the Thames Embankment near the Palace of Westminster.

"You can't really put a price on these sorts of clocks," says Fjodor.

"There is the historic value, the provenance, and a lot of the clocks are one-offs, so they're priceless."

Each clock will be brought in for a full service every 10 to 15 years, which sees Fjodor take it apart and clean it.

"There will be a little wear [to parts] that will need repairing, I'll then lubricate the mechanism and put the clock back together."

There has been an in-house clockmaker at Windsor Castle since the late 1970s, with Fjodor being the fourth horological conservator.

"My predecessor was here for 20 years, his predecessor was working for around 30 years, so I think it's a job for life.

"I'm thankful I've managed to land this job quite early in my career, so I do hope I'll be here for quite a while."

Photos by Antonio Olmos.