The Balkans on film, 25 years since the Dayton Agreement

- Published

December marks the 25th anniversary of the signing of the international peace treaty known as the Dayton Agreement, which brought an end to nearly four years of conflict in former Yugoslavia.

Since then Scottish photographer Chris Leslie has been visiting the Balkans and capturing how its people and places have changed.

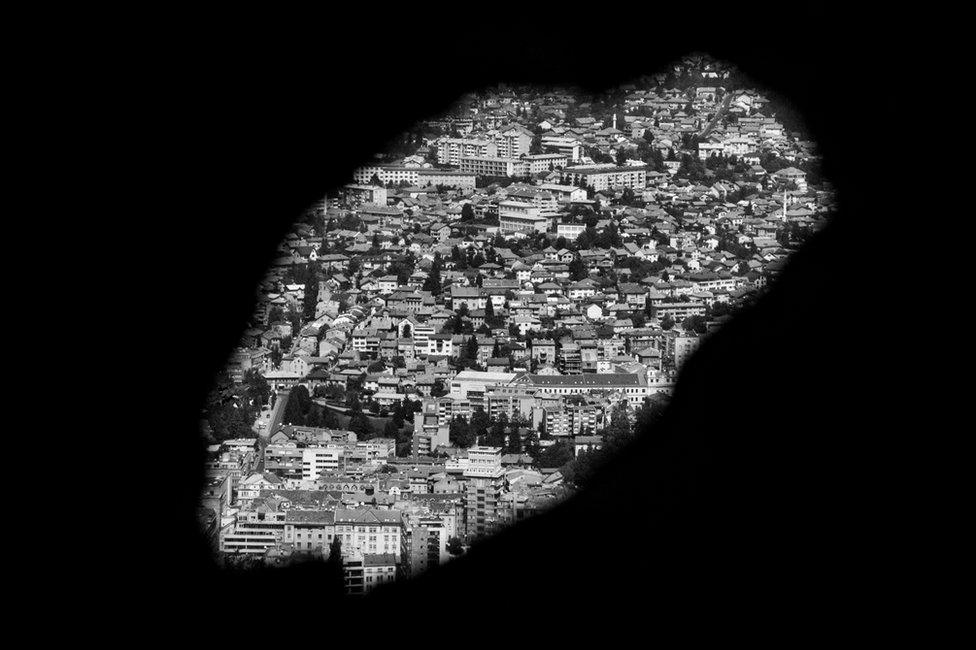

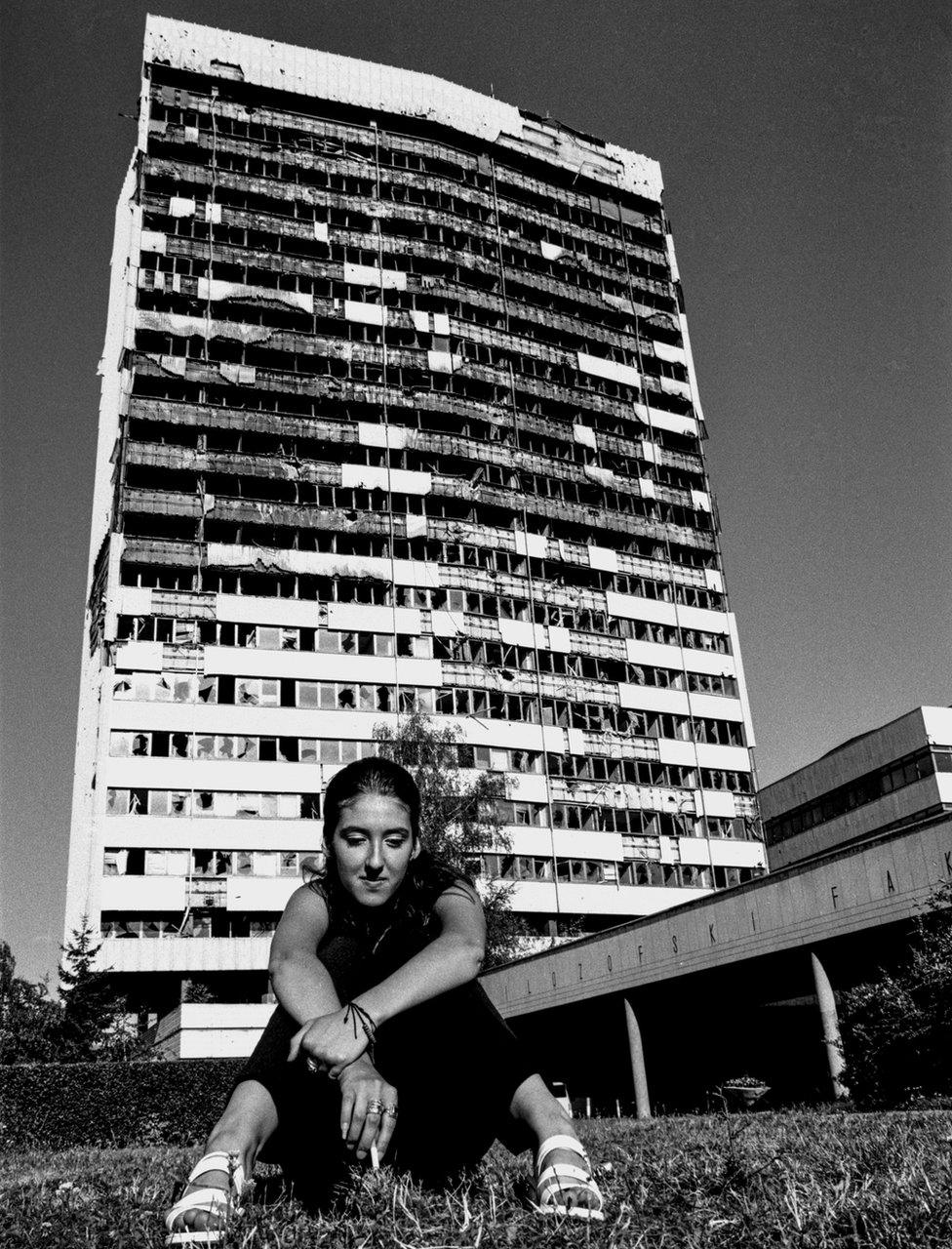

Snipers' view, Sarajevo, 1999

Between 1992 and 1995, the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina claimed more than 100,000 lives and made around two million people homeless.

To bring an end to the bloodshed, the Dayton Peace Agreement was officially signed by the presidents of Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia in Paris on 14 December 1995.

(front, left to right) Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, Croatian President Franjo Tudjman, and Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic sign copies of the Dayton Peace Agreement in the Palais de l'Elysée, Paris, on 14 December 1995 as world leaders look on

The agreement came after 21 days of negotiation at the Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, and was driven by US President Bill Clinton and his team.

"No-one outside can guarantee that Muslims, Croats and Serbs in Bosnia can come together and stay together as free citizens in a united country sharing a common destiny," President Clinton said at the time.

"Only the Bosnian people can do that."

Refugee mother and baby, Sarajevo, 2003

The former Yugoslavia was a Socialist state created after German occupation in World War II and a bitter civil war.

The federation of six republics brought together Serbs, Croats, Bosnian Muslims, Albanians, Slovenes and others under a comparatively relaxed communist regime.

The leadership of President Josip Broz Tito successfully suppressed tensions until his death in 1980.

Without Tito, there emerged calls for more autonomy within Yugoslavia by nationalist groups, leading to declarations of independence in Croatia and Slovenia in 1991.

The Serb-dominated Yugoslav army lashed out, first in Slovenia and then in Croatia.

Thousands were killed in the conflict in Croatia which was paused in 1992 under a UN-monitored ceasefire.

Ruins of the city of Vukovar, Croatia, in March 1992

Bosnia was next to try for independence. Bosnia's Serbs resisted and war ensued with over a million Bosnian Muslims and Croats driven from their homes in ethnic cleansing.

The capital Sarajevo was besieged and shelled.

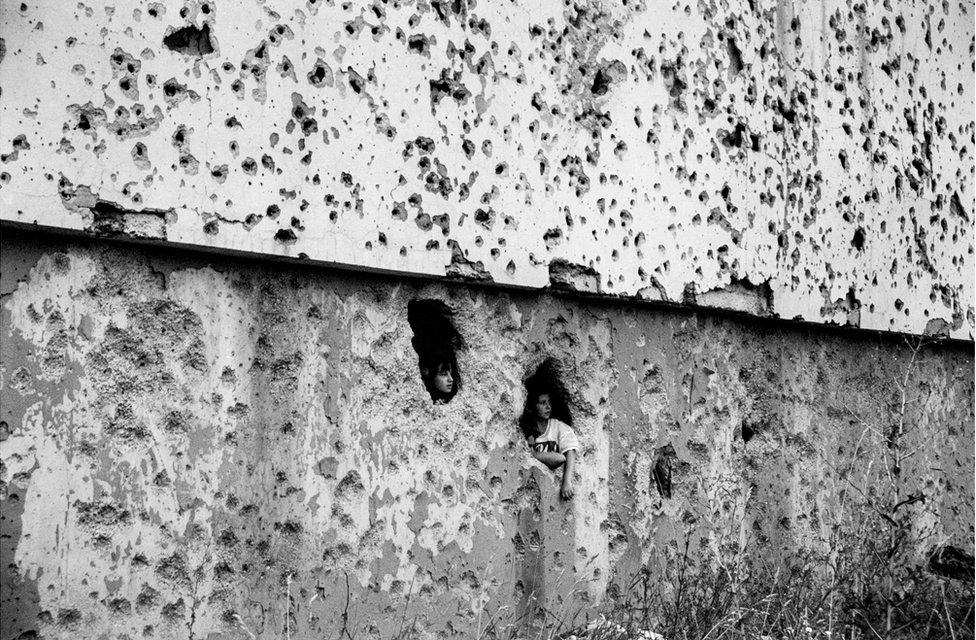

Dobrinja, former front line suburb of Sarajevo, 1996

After Nato bombed the Bosnian Serbs, Muslim and Croat forces made gains on the ground and ended the war.

The Dayton Peace Agreement divided Bosnia into two self-governing entities, a Bosnian Serb republic and a Muslim-Croat federation lightly bound by a central government.

The Dayton Agreement may have brought peace to the Balkans, but huge numbers of people were displaced and unemployed.

Bafta-winning photojournalist and filmmaker Chris Leslie, from Scotland, has been visiting the Balkan region for nearly 25 years, documenting the war-ravaged towns and cities of former Yugoslavia.

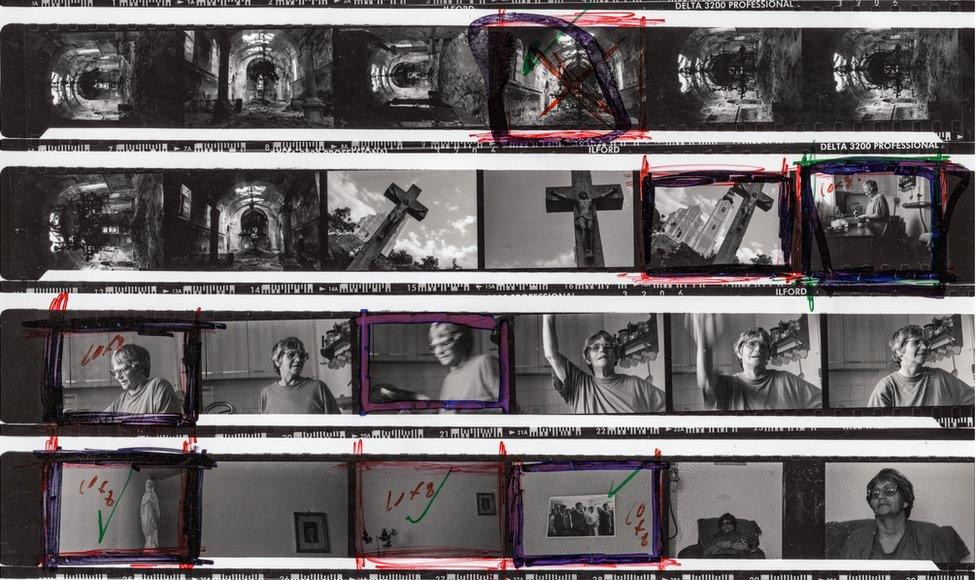

A photographic contact sheet by Chris Leslie showing images from Pakrac, Croatia

In a new photographic book, A Balkan Journey, external, Leslie reflects on how the landscapes and people of post-war Balkans changed since the Dayton Agreement.

In 1996, Leslie volunteered with an NGO to work in the war-torn town of Pakrac in Croatia, to help run a project that taught children black and white photography.

"Pakrac itself was in ruins - estimated to be 85% destroyed during the war with tension and divisions still high," he says.

A "cleansed" home, Pozega Road, Pakrac, 1996

"A sense of menace and a low-lying level of stress permeated life in the town.

"Sporadic explosions could still be heard as animals set off landmines in the surrounding fields, a handy reminder not to venture off the pathways or beaten track."

Destroyed Orthodox church, Pakrac, 1996

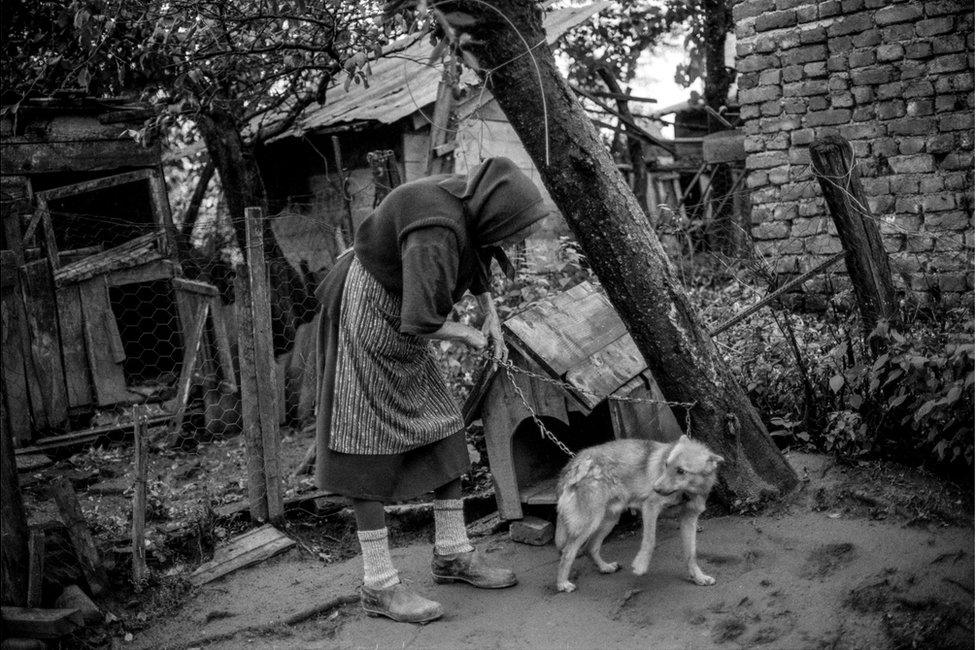

During his visit, Leslie spent time with Ljuba Gajic (below), an 80-year-old Serb woman who lived alone in a small, partially destroyed house.

Unlike her family and friends who were fearful of living in a newly-independent Croatian state, Ljuba had chosen to stay in Pakrac with her six chickens, three cats and dog called Jonny.

Ljuba Gajic outside her home, Pakrac, 1996

When Leslie came to leave Pakrac in November 1996, he shared a tearful goodbye with Ljuba.

"Ljuba poured us all one final plum brandy and with tears rolling down her cheeks, she clasped my face towards her and said I was like a son to her.

"Then in the same breath she swore at the then Croatian president for ruining her life and shook her fists in the air."

Ljuba Gajic and her dog Jonny, Pakrac, 1996

Inspired by the work he had done in Pakrac, Leslie travelled to Sarajevo in 1997 to set up his own photo project for children: the Sarajevo Camera Kids.

Oggi Tomic, Camera Kid, Sarajevo, 1997

Using donated equipment from Scotland, he set up a darkroom in the basement of an orphanage.

He was soon overwhelmed with interest.

"Children ran freely around their playgrounds and streets and photographed anything and everything that interested them.

"[It was] a creative outlet for these kids who had dealt with a near lifetime of war and siege."

Oggi Tomic, Camera Kid, Sarajevo, 1997

Leslie worked on the project for three consecutive summers.

In 1998 he met Una Mesic, 24 (below).

Una Mesic at the Parliament Building in Sarajevo, 1998

"Can we talk about justice?" she asked him.

"It's hard to talk about justice for all those families who lost their loved ones, their friends.

"There are a lot of mothers in Bosnia still searching for the bones of their children.

"There is no point talking about buildings, infrastructure, the economy - these are all possible to rebuild, but it's impossible to bring back those we lost."

Oslobodjenje newspaper offices, Sarajevo, 1998

Davor, former football coach, Sarajevo, 2003

In 2004, Leslie visited Kosovo after the 1999 Kosovo war.

"I saw a landscape in ruins.

"A third of its housing stock - 120,000 homes - had been destroyed or rendered uninhabitable.

"Homes in the former Yugoslavia did not just suffer damage as a result of war - they were intentionally destroyed, dynamited, and sometimes booby-trapped so no-one could ever return."

The Missing, fence outside Kosovar parliament, Pristina, Kosovo, 2004

Leslie visited Sarajevo again in 2015 to document the 20th anniversary of the Dayton Agreement.

Graffiti, Sarajevo, 2015

He spoke to student Kerim Rozajac, 20 at the Underground Nightclub in downtown Sarajevo.

Kerim Rozajac, Underground Nightclub, Sarajevo, 2015

Kerim told Leslie: "A lot of people in Bosnia are considering peace as something unusual and special, thus accepting every kind of injustice from the government."

On the same expedition, Leslie met Bozo Jevric, 62, who served as a Bosnian Serb soldier.

"The best thing about Dayton was that I could give up my gun," said Bozo.

Bozo Jevric at his home in Planinica, Vares, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2015

"War is in the past and our future is working together.

"It's the only way our village will survive."

Leslie's most recent trip to Sarajevo was in 2018.

"The city now puts on a brave, bold, cosmopolitan face, a modern European tourist destination like any other," he says.

A view of Sarajevo, 2015

A Balkan Journey is funded by Creative Scotland.